Discovering the Sicilian-Americans with the Cinisi Mayor, Giangiacomo Palazzolo

An old Sicilian saying states “La lontananza ‘un abbannuna amuri, chiuttostu menti ‘na vampa ‘nto cori” (Distance doesn’t cause us to forget love. Actually, it creates a spark within the heart). Profoundly rooted in the spirit of every immigrant is this fire, the love for his homeland that distance certainly doesn’t cause him to forget. Rather, this distance actually exalts and idealizes the country. A bittersweet union between nostalgia for one’s homeland and the celebration of it live in the hearts of many Sicilian communities that have been in America for generations. The Sicilian Americans are the biggest and most important group of Italian origin in the U.S., and their story goes back to the times in which Italy wasn’t yet united. The regional folklore is strongly differentiated.

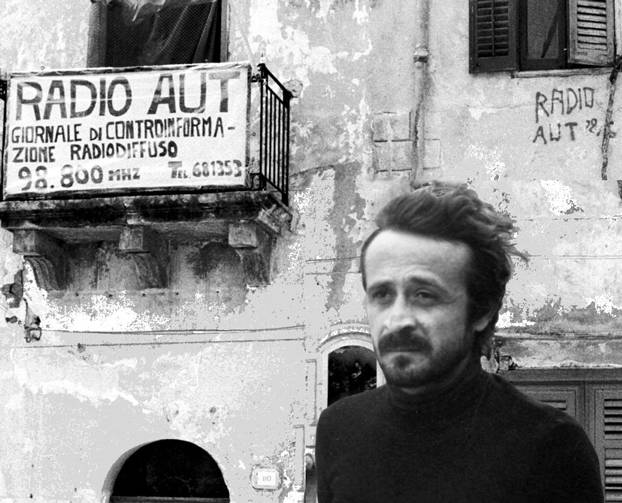

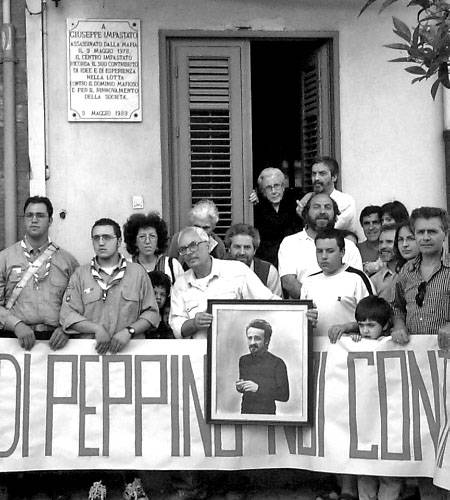

We met Cinisi mayor Gianfranco Palazzolo during his visit to New York to hear his extraordinary experience whit the Sicilian communities abroad. Speaking with Palazzolo you get the feeling that you’re speaking with an old fashioned Sicilian intellectual, deeply enamored by his native land but also critical in regards to it. With his help, we were able to get a snapshot of aspects that represent modern Sicily. This illustration extends from socio-political subject matter to subject matter that is more cultural and way-of-life focused: for example tourism and integration of foreigners into the Sicilian culture. It also considers the phenomenon of the mafia and of the historic figure of Peppino Impastato, a Cinisi activist and journalist who was killed by the mafia in 1978.

What is the reason for your visit to America?

The necessity to physically embrace the immigrants that feel a strong need to have contact with their native country, and also to ask for forgiveness from our fellow countrymen because our country was not able to give them what they deserve. I also wanted to create relationships that can promote the Italian culture, and create an exchange for young American students to go to Italy and vice versa. This is a program that we are realizing here in New York. We also would like to establish relationships that are economic in nature, so we met with the presidents of the Chambers of Commerce in Chicago and New York. We believe that we have great niche products that could surely be exported and that represent the culinary culture of Italy.

Which products are you specifically referring to?

Above all, the Cinisara cow. In southern Italy there are two types of cows, the Modicana/Ragusana and the Cinisara. These cows have particular organoleptic characteristics and their products are very light like the milk that is used for cheese with exceptional taste. They are also used for a very particular cut of meat. In some Italian restaurants we have carpaccio made from Cinisara cows or caciocavallo cheese made from the Cinisara cows.

Could you tell us a bit more about your trip to Chicago, Detroit, and New York?

In Chicago I saw the first generation of Cinisari, and I was a bit sad because many of them haven’t been to Cinisi for decades. Feeling down, I spoke with many people that couldn’t go back because of economic difficulties. That said, their fondness calmed my sadness. Instead in Detroit, I saw a very rich community that decided to live without wanting to integrate into the American mainstream culture. I left my heart there; I saw Cinisari with classic values, traditions, and big hearts. The community in New York, in addition to being wealthy, is also integrated in the American culture and cosmopolitan.

I had come to help the Cinisari remember their country, but by the end of the trip, they reminded me what Cinisi is really about, the true values, the traditions, the stories. The Cinisaris’ big hearts are easier to see here, rather than in the town itself.

There is some kind of preservation that happens, distancing yourself makes you want to keep a snapshot of the time in which you leave, and this photo is preserved in a meticulous manner in your heart.

A few years ago airlines had launched economical round-trip air routes from New York to Palermo’s Falcone/Borsellino airport, which is in the Cinisi area. What was the importance and the nature of this phenomenon in terms of tourism and cultural integration?

Many people speak of Cinisi saying it is an exceptional town because it has both the sea and the mountains; I say that yes, this does make it exceptional, but it’s also unique because it has something that nobody else in Sicily (aside from Catania) has: an airport that is part of Cinisi area. It is a source of enormous wealth for my area. Investments in the airport are continuous and limitless, and the number of passengers is also increasing. At this point we have 6 million passengers every year; therefore, it is crucial for our economy. There are several ways to benefit from having an airport. It not only helps tourism, but it’s also an ingress for commerce. The movement of such important passengers is something to take advantage of. Activities in my town are growing in both quantity and quality, and this is linked to the accommodation of tourists. Cinisi has become the door to Southern Italy, an important layover.

What changes have you seen in that sense?

The difference can be seen right away. Given that we didn't have that much tourists, we were not used having people in the area that speak foreign languages. Now we are beginning to open ourselves up to foreigners and to the use of foreign languages.

Let’s talk about the phenomenon of the mafia. What do you think the true face of the mafia is today, and how much does it play into the cliche collective imagination about Sicily?

I really like the image that the that the mayor of Palermo gives about today’s organized crime. In past years we used to have a mafia that had a vertical hierarchy; there was a boss with his colonels and his soldiers. Today, the organized crime that we have in Sicily - deemed “mafia” - has different characteristics than that of the past. Now we have a horizontal organization; there are no longer singular bosses that act in an almost autonomous manner. We have various, unconnected levels in these horizontal strips. Organized crime of the old days was based on typical crimes. Now there are higher-level crimes of white collar workers who are interested in the waste sector. In my opinion this is the most dangerous part of this new Sicilian criminal context because there is a lot of money that is being taken from that sector, and therefore essential services will be undermined. The consistent interference of specific criminals is a big danger for Sicily.

Is this influencing the Sicilian economy? What are the causes of the economic crisis that has also hit Sicily?

The mafia has no part in this. Criminals intervene where there is wealth. This wealth is neither produced as a result of cultural reasons nor by our administrative machine to take advantage of European resources. A paradoxical inability exists at the bureaucratic level. There is no development on the rise; the problem with the managing class is that it belongs to a generation that is surpassed by facts and laws, in its way of communication, and in it’s approach to education. This generation isn’t suited for the time in which it’s living, and it’s not in a position to benefit from the many resources that it has. However, I do need to highlight the positive changes in the last two years. I am a mayor that doesn’t practice politics. I’m non-partisan, and I have civil lists, and I’m not involved with political parties. That said, with the arrival of Renzi, I noticed a major professionalism from the bureaucracies and a much greater capacity for them to use resources that then returned to my town. For example, over the course of two and a half years, we received up to 12 million Euros in public funding.

Can you tell us anything else about Peppino Impastato, the historic figure that was a Cinisi native?

The truth is that he was an extremely courageous person. Today it’s easy to attack mafia. Today I can say “the mafia is a mountain of shit” (a historic saying from Peppino Impastato, NdR), and sleep soundly without worry about it. Saying it in the 70’s was indicative of exceptional courage that also highlighted a moment of a “cultural break” between the old vision that the country had about certain personalities, and the new vision that was about to come. Through his courage, he embodied that moment of “breaking.” Liberation and the cultural revolution of my region were born from him.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+