Jazz and the Value of Immigration

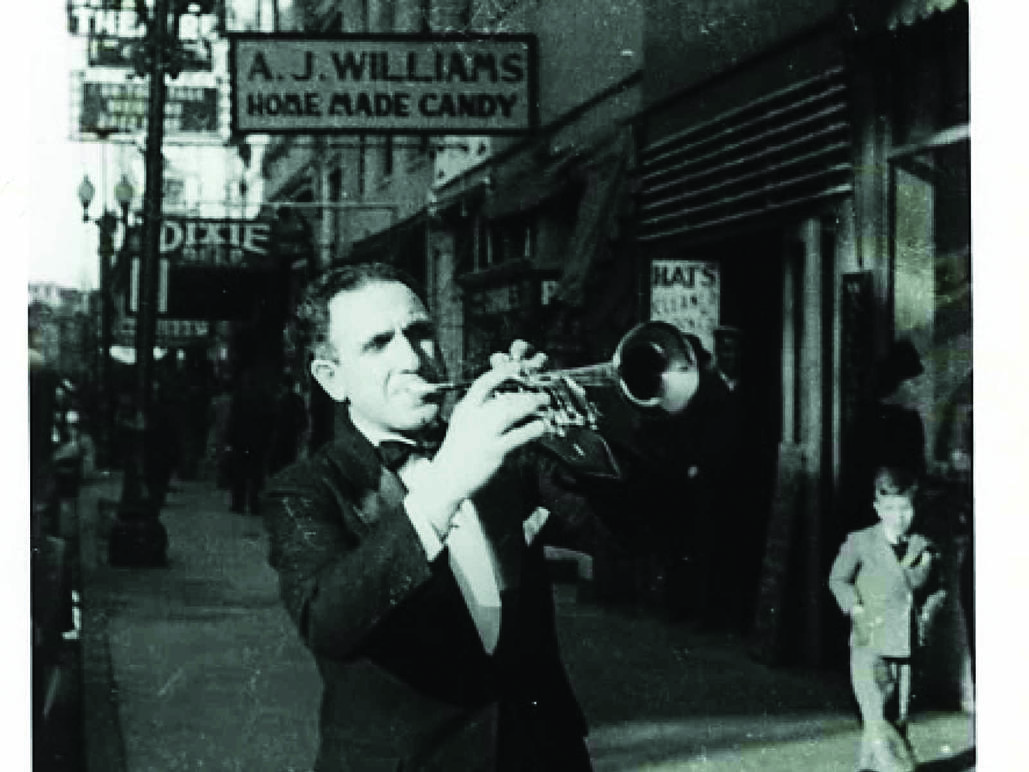

Every major artistic form of universal worth is born from migration. These cultural shifts become unstoppable thanks to their communicative force, and are therefore also physical transformations, in the broadest sense, moving from one place to another. It may be the subject of a lot of debate, but today it is generally accepted, even held up as an example of the brotherhood between different countries, where borders are nothing more than lines drawn on a map. They don’t exist in nature. Often they’re the outcome of wars and deals struck under (clearly non-peaceful) pressure. Jazz is no exception; indeed, it’s a prime example of a cultural phenomenon regarded as among the most beautiful and visionary of the twentieth century and the present moment. No doubt it will be in the future too. Jazz music was born over a hundred years ago in the slums of New Orleans thanks to the melting pot of races, ethnicities, lifestyles, styles of talking that Louisiana’s great port city represented. It’s as if at that time and in that place—more than any other place—there was a confluence of major talents and personalities from all around the world. Especially Italians, French, Irish, Creoles and, naturally, Africans—who came bearing various kinds of music that had emerged out of other melting pots.

The rhythm gained importance because, given its steady cadence, it was easy to dance to. The melodies, on the other hand, took on various shades: the Creoles with their blend of sensuality and melancholy; the Irish with their spectacular dancing; the French with their more sophisticated harmonies; the Italians with the drama of opera and the dances of the South. The Africans, enslaved at the time yet proud of their roots, bore complex rhythms and songs of suffering that would become the Blues. Out of this human carousel, jazz was born. And it developed in places that nowadays we’d consider the least likely to produce noble art: whorehouses. The first great maestros got their start there, trying to pluck a joyful note to entertain both johns and prostitutes.

Like a grand tour crossing cultures, continents and moods. So, what would become the most representative and sophisticated music of our times was born spontaneously and—as they say—“from the bottom up.” From the outset, the Italians were fundamental to boosting the birth of jazz, first in New Orleans and later in Chicago and New York, until arriving—we might say “returning”—to Italy itself, the bel paese in the middle of the Mediterranean. American troops were the ones to bring jazz to Italy, when the first World War broke out and Americans decided to intervene. And where did those soldiers come from? From the Port of New Orleans, where they’d been stationed and where they’d heard the first notes of “Jass,” which later became Jazz, a name many believe comes from the local slang for having sex. As you see, the major movements start with the little things, even the most intimate. It took time for Jazz to become a “noble” art form, because racists were always labeling the music lowbrow, only good for dancing. But real, genuine culture always wins the day. Let’s hope those who would bar free movement remember that; they fail to realize that one day their children and grandchildren might enjoy something they disdain: the pleasure of self-improvement gained by beauty and art. A border never gave us that kind of joy.

Every major artistic form of universal worth is born from migration. These cultural shifts become unstoppable thanks to their communicative force, and are therefore also physical transformations, in the broadest sense, moving from one place to another. It may be the subject of a lot of debate, but today it is generally accepted, even held up as an example of the brotherhood between different countries, where borders are nothing more than lines drawn on a map. They don’t exist in nature. Often they’re the outcome of wars and deals struck under (clearly non-peaceful) pressure. Jazz is no exception; indeed, it’s a prime example of a cultural phenomenon regarded as among the most beautiful and visionary of the twentieth century and the present moment. No doubt it will be in the future too. Jazz music was born over a hundred years ago in the slums of New Orleans thanks to the melting pot of races, ethnicities, lifestyles, styles of talking that Louisiana’s great port city represented. It’s as if at that time and in that place—more than any other place—there was a confluence of major talents and personalities from all around the world. Especially Italians, French, Irish, Creoles and, naturally, Africans—who came bearing various kinds of music that had emerged out of other melting pots.

The rhythm gained importance because, given its steady cadence, it was easy to dance to. The melodies, on the other hand, took on various shades: the Creoles with their blend of sensuality and melancholy; the Irish with their spectacular dancing; the French with their more sophisticated harmonies; the Italians with the drama of opera and the dances of the South. The Africans, enslaved at the time yet proud of their roots, bore complex rhythms and songs of suffering that would become the Blues. Out of this human carousel, jazz was born. And it developed in places that nowadays we’d consider the least likely to produce noble art: whorehouses. The first great maestros got their start there, trying to pluck a joyful note to entertain both johns and prostitutes.

Like a grand tour crossing cultures, continents and moods. So, what would become the most representative and sophisticated music of our times was born spontaneously and—as they say—“from the bottom up.” From the outset, the Italians were fundamental to boosting the birth of jazz, first in New Orleans and later in Chicago and New York, until arriving—we might say “returning”—to Italy itself, the bel paese in the middle of the Mediterranean. American troops were the ones to bring jazz to Italy, when the first World War broke out and Americans decided to intervene. And where did those soldiers come from? From the Port of New Orleans, where they’d been stationed and where they’d heard the first notes of “Jass,” which later became Jazz, a name many believe comes from the local slang for having sex. As you see, the major movements start with the little things, even the most intimate. It took time for Jazz to become a “noble” art form, because racists were always labeling the music lowbrow, only good for dancing. But real, genuine culture always wins the day. Let’s hope those who would bar free movement remember that; they fail to realize that one day their children and grandchildren might enjoy something they disdain: the pleasure of self-improvement gained by beauty and art. A border never gave us that kind of joy.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.