Sanremo Festival: the Mirror of Italian Customs

This year Sanremo is in its 59th edition, an important goal for a show that was born in 1951 with among its aims, a wish to promote the use of Italian language when a good portion of the population still spoke regional dialects. In those years following World War II, the festival of Italian song was also seen as useful for helping people move on from the war period, as a distraction that could create economic developments in the field of entertainment, which had not been fully exploited in Italy as it had been abroad. At that time the city of Sanremo was still recovering from those last reverberations of war, and its Teatro Comunale had been destroyed by air bombings. There was a strong will to leave the past behind and restore the city to the center of tourism it had once been.

The first editions of the festival aired on the radio, and then from 1955 onwards on television. In the beginning songs dealt mainly with banal, simple, familiar, somewhat anachronistic and surreal themes, such as poppies, ducklings, little houses in Canada, old boots. In 1958 Domenico Modugno’s cry “volare” represented a shake, a sort of awakening signaling that the society was changing, with a nod to rock and roll and other musical influences from around the world. The lyrics of the songs started to change too, drawing inspiration from topical facts. All this culminated in the first scandals that in every edition are a “must”, inevitable occurrences. Like in 1959, when Jula De Palma, performing a sensual song, “Tua”, spurred protests from viewers who thought her long dress too closely resembled a nightgown and that her sultry voice was too provocative. In 1960 Modugno’s song “Libero” was considered by some conventional thinkers as a threat to the unity of family. It can safely be said that since its birth there has never been a boring, uneventful edition of Sanremo! In 1967, though, the festival turned tragic: Luigi Tenco, a singer excluded from the competition for his subversive entry, a song that was a criticism of modern society, killed himself in his hotel room. There is still a dark shadow that hangs over that year of the festival, with a recurring hypothesis made by some of Tenco’s friends, who assert he was killed. The motivations behind his extreme act remain mysterious.

The festival has been witness to the evolution of Italian generations and the influence of historic events on their society. For instance, “Proposta” by the group I Giganti, was performed at Sanremo in 1967 and represented a rejection of the war in Vietnam, with a refrain that incorporated the famous pacifist slogan “put flowers into your guns”. Another, “Chi non lavora non fa l’amore”, a 1970 song by Adriano Celentano, analyzes the difficulties of a worker on strike. From the Sixties on, many of the songs of Sanremo treated the problems of everyday life and the competition left space for gossip about the festival’s cast, not just the singers. With time it has become a customary event, snubbed by intellectuals, but avidly followed and commented during its broadcast. It may seem paradoxical, but especially in the last years, the festival tends to be commented even before it begins, because of the many rumors and gossip items propagated by agents and press reports, seeking to work up as much attention as possible. Of course, emphasis is given to everything but the songs themselves, which should be at the center of the event!

This year, however, one song by Povia is already under the media lens for its contentious topic. The title is self-explanatory: “Luca era gay”. Generally the lyrics of song entries are released before the contest. And so it was year too, with the exception of Povia’s lyrics which were kept unknown. Naturally this built curiosity around his song, and meanwhile the title alone had the effect of mobilizing Italian gay and lesbian associations. Indeed Povia declared that in his opinion it is possible to heal from homosexuality, as he considers it an illness. Gays and lesbians prepared a series of protests in Sanremo to raise awareness on a subject “that cannot be viewed as a musical-media operation, representing an ever-present wound for all those homosexuals in Italy who are still fighting against homophobia and ignorance”.

There are further controversies regarding the payment of Paolo Bonolis, the show’s host, who stands to make one million euros: a “scandal” according to critics who feel the sum is unwarranted during a time of economic crisis. Bonolis defends his remuneration, claiming that he has worked on the Sanremo project every day for the past year and that the sum given to Pippo Baudo for the last edition of the festival was almost the same (900.000 euros). Roberto Benigni’s paycheck for the event, 350.000 euros, has also been seen as excessive. The representative of the center-right party PDL, Maurizio Gasparri, challenged Benigni, a famously outspoken leftist, and proposed he do the right thing “as man of the left, and give the 350.000 euros to the redundancy fund beneficiaries”.

The appearance of contestant Mariano Apicella on Sunday February 22 is also highly anticipated. The Neapolitan, a former unlicensed park attendant who used to sing traditional songs while “at work”, was “discovered” years ago by Italian premier Silvio Berlusconi during a visit to Naples. Apicella’s life was radically reversed by the encounter: today he is rich, famous and together with Berlusconi, the co-author of three albums of romantic Neapolitan music. Paolo Bonolis dares not confess it, but the icing on the cake for his edition of the festival would be the surprise appearance of the premier during Apicella’s performance.

The 59th edition of Sanremo is ready to provide its usual supply of scandals, gossip, distractions: an event often criticized, sometimes loathed and yet secretly and hungrily watched. Representing a sort of holy ritual before springtime, Italians have not been able to give it up ever since that fateful first show in 1951.

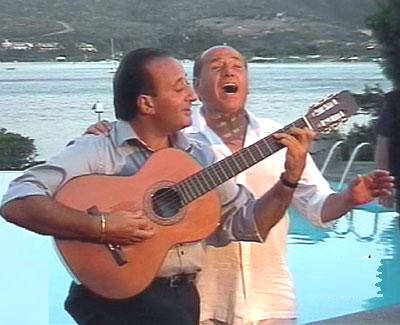

Fiorello-Benigni a Sanremo 2002

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.