Day of Reckoning Approaches for Premier Renzi and for Italy

ROME -- Just weeks after celebrating his 1,000 days in office, a feat matched by only four previous postwar Italian governments, Premier Renzi faces a tough constitutional reform referendum Dec. 4. His achievements during those thousand days are far from negligible. While having to confront such horrors as this autumn's earthquakes in Central Italy, under Renzi's tutelage 655,000 jobs have been created, and unemployment reduced by over 1%. A much-needed voting reform act is under negotiation; the European Union is at last to fund the refugee crisis Italy has been handling valiantly on its own; and a law permitting civil unions has been passed. Athough the economy remains sluggish, it is making progress, with the GNP up 1.6% since early 2014, according to ISTAT. Family consumption is also up by 3% over the same period of Renzi's government.

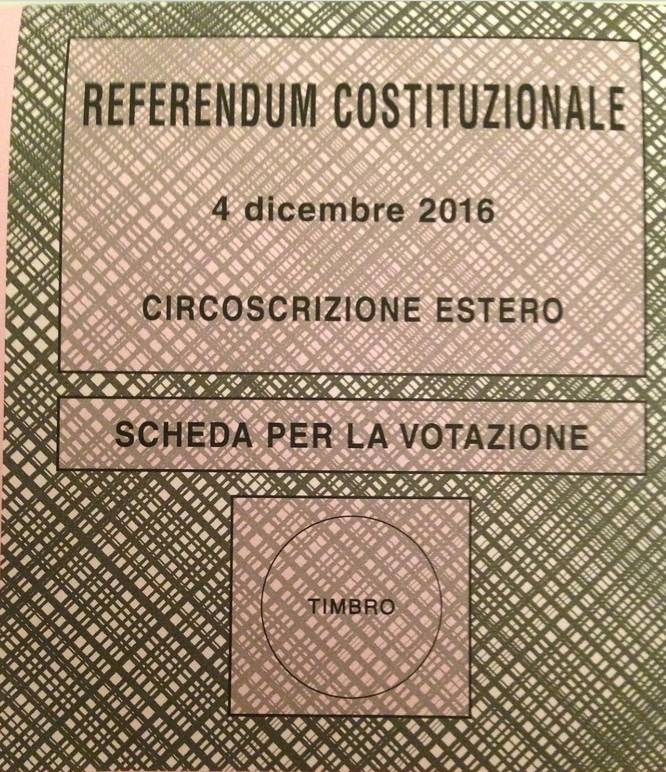

Premier Renzi's pride in these achievements are, however, seriously undermined by the approaching constitutional reform referendum taking place Dec. 4. In this highly controversial ballot, Italians, including those living abroad, are called to vote the reduction of the present 315-member Senate to an assembly of just 100 members: 95 regional representatives or city mayors plus five nominated by the President (but only for a seven-year term rather than, as now, lifetime). The powers of this smaller Senate would be drastically curbed, making it no longer the equivalent of the Chamber of Deputies, and ineligible to participate in a vote of confidence for a new government.

Behind the referendum is the theory that today's equivalency between the two legislative bodies is the cause of endless legislative slow-downs as bills bounce back and forth. The referendum is also expected to bring savings to the state because the new Senate members would be unpaid. In addition, the 110 provinces, which are more or less the equivalent of U.S. county governments, would be abolished as superfluous.

These are only a few of the main points. In effect, the referendum text is long and so viciously complex that only the most ardent voters are expected to sit down and read every detail. (Give it a try at >>). The result is that, although Premier Renzi has fought to avoid its outcome being read as a vote for or against himself and his government, that is what is happening.

The release of polling statistics for or against the referendum is now disallowed until after the vote takes place, but as of November 18 (in a DEMOS poll on the last possible day), the "no's" were well ahead of the "si's" which Renzi is seeking, 41% vesus 34% with 25% undecided. Renzi's own popularity has waned: when he became premier at age 39, his PD party won 41% in the EU elections. Today, its popularity stands at only some 30%, slightly ahead of the M5S according to some pollsters, but behind according to others. (For comparitive poll results, see: http://scenaripolitici.com/)

The battle against the referendum created an unlikely coalition of anti-Renzi forces, including within his own party. Alligned with the "no's" is former Premier Massimo D'Alema of Renzi's own Partito Democratico (PD) and his followers. Leading that coalition is Beppe Grillo's Movimento Cinque Stelle (M5S). The Northern League headed by Matteo Salvini is another adversary; populist right and left are hence best buddies. (Among those fearful of this alliance is former Premier Silvio Berlusconi, whose party vestiges risk being overwhelmed by the tandem M5S and Salvini; some believe that, playing his cards carefully, he is allying himself with Salvini so as to rein him in.) The mainstream media as well as Confindustria support Renzi, while the opposition expertly exploits the social media.

Just as with Brexit and the Trump triumph, the implications go beyond Italy and into all Europe itself because a vote for no could lead toward Italy, second largest EU economy, moving out of the Euro. The future is therefore of great interest beyond Italy itself. The big question is this what happens if the nays have it? Will Renzi and his government be obliged to resign? If so, who will succeed him -- a so-called "temporary" executive government (temporary for what)? Headed by whom?

Given the populist success of Brexit and Trump, the Italian populism as expressed by Grillo and Salvini implies that new elections might be an outcome. However, new elections are said to be possible only after passage of a revised election law, billed as the Italicum. But herein lies a problem: in the bill the Italian supreme court has found six possible instances of constitutional irregularities. The court is not expected to pronounce upon these until at least January. Without that new law, general elections appear unlikely. This makes a post-Renzi technical government a real possibility, even if, in the end, headed by Renzi himself.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.