Remembering Sicily's Slain Anti-Mafia Judges

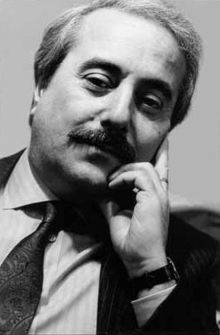

In Washington, D.C., FBI director Robert S. Mueller spoke Friday in a commemoration at FBI headquarters. Also in Washington, the Italian ambassador will host an exhibition devoted to Falcone, in which - for the first time - ten photographs and a selection of documents which narrate the Falcone story will go on view Tuesday, May 22. The exhibition catalogue is published by Gangemi Editore; sponsor is, together with the Italian embassy, the Compagnia per la Musica in Roma.

In Turin in North Italy, Gustavo Zagrebelsky has organized a series of programs dedicated toFalcone and his similarly slain colleague Paolo Borsellino, assassinated July 19 of the same year, 1992, called "For Legality." Among the participants are a number of mayors from towns which have suffered from the Mafia. This ambitious project includes readings in theaters, film showings, concerts and several public debates. Justice Minister Paola Severino will conduct a dialogue on the Mafia together with Zagrebelsky, who is president of the Biennale Democrazia. Our goal, says Zagrebelsky, "is to save legality in Italy."

In addition, a new book edited by Antonella Mascali, "Le ultime parole di Falcone e Borsellino" (Falcone's and Borsellino's Last Words, published by Chiarelettere), is making waves here in Italy. "The more the years go by, the more uncomfortable I become with participating in these public ceremonies commemorating the assassinations," writes Roberto Scarpinato in the introduction. "Falcone and Borsellino were assassinated because their work as extremely correct magistrates culminated in the convictions at the maxi-trial, making them the very symbol of a state which had struck a mortal blow against Cosa Nostra, and shattered the myth of its invincibility." The reason for his skepticism, as he goes on to explain, is that the Mafia has been all too often presented as the rotten apple in the barrel. Only occasionally is there mention of white-collar collusion.

Having reported on the Maxi-trial for both Time magazine and the Wall Street Journal, and on the Mafia drug wars in that period for the BBC, I can only agree. In that period I asked a courageous magistrate, whose brother had been assassinated in his place, why the Italian state failed to tackle and defeat the Mafia in the same way that it had defeated terrorism. His reply: "The terrorists were against the Italian system. The Mafia is the system."

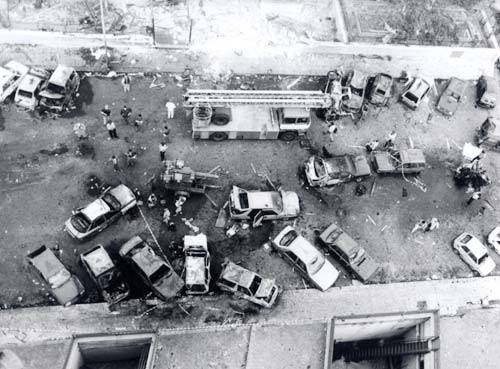

If this former magistrate is to be believed, then, it was the system which murdered Falcone, his wife Francesca Morvillo (also a magistrate) and his three bodyguards. Two months later the system also eliminated Borsellino and his five bodyguards when his car was, like Falcone's, was blown up.

As a foreign correspondent, I could hardly be expected to know much of the inside story of all this. But at the same time very few local Palermo reporters knew much more. I was sent, for instance, to interview the then head of the secret services in Palermo, a pleasant enough man, originally from Rome, named Bruno Contrada. A former police chief of Palermo, he headed the famous "flying squad" of detectives before becoming deputy director of the civil intelligence service SISDE. On Dec. 14, 1992, he was arrested for "external concourse in association with the Mafia" on the basis of admissions made by a number of Mafia bosses under arrest, including Tommaso Buscetta (the so-called pentito who was particularly helpful to Falcone), Gaspare Mutolo and others.

Reading of Contrada's first conviction and subsequent appeals, I found it difficult to believe that someone in such a crucial position could be guilty. But in 2007 Italy's supreme court of Cassations upheld Contrada's conviction to ten years in prison. The following year Contrada's lawyers asked for him to be released to house arrest at his sister's home in Naples on grounds of poor health; he had lost nearly 50 pounds. The request was granted. When Paolo Borsellino's brother, Salvatore, complained about the release, Contrada's lawyers threatened to sue Salvatore Borsellino for defamation.

On the day the maxi-trial opened in Palermo back in TK there was great excitement. A gigantic courthouse had been specially built with a secure tunnel that meant that the alleged Mafiosi could be introduced into the courtroom. It was difficult to ignore what looked like a a giant WWII cement pillbox, and so I went knocking on the doors of the apartment buildings that overlooked the courtroom. "I don't know what goes on in there," said one starchy woman. "None of my business."

The US and France too thought it was their business, at least, and Borsellino, Falcone and the others in the anti-Mafia pool (as it was called) shared evidence with other investigators for the successful prosecution in both those countries of the "pizza connection," which was in fact a drug connection linking New York to the world center of heroin manufacture at that time (the Eighties). What should not be forgotten, in this year's commemoration, is how many obstacles which "the system" placed in the way of these outstanding judges, prosecutors, magistrates and simple policemen, like my detective friend Michele, who took the place of his own slain boss, Boris Giuliano.

By the way, only a few hours ago the Francesca Morvillo High School in the Southern town of Brindisi - named for Falcone's murdered wife - was bombed, killing one and wounding seven.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.