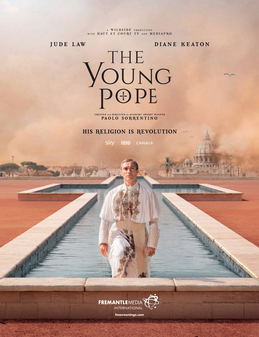

The Young Pope and a Few Questions About God

With the season winding down, hordes of people continue to tune into Paolo Sorrentino’s The Young Pope, myself included. Every week I’m further surprised by how much the Neapolitan lmmaker’s monumental opus inspires a believer like me to re ect on faith, to ask the big questions about God and why we go before Him.

I’m well aware that many clerical circles regard the series with suspicion and, perhaps misguidedly, have already branded it irreverent and sacrilegious. But I think the show is immensely spiritual insofar as it posits questions that man has long posited yet struggles to ask today. But there remain and will remain monuments of philosophical and theological searching. So, the perennial questions, but in a fresh language that could prove interesting to theologians and the Church from the standpoint of method, for introducing new words with which to understand the world.

The grand style of The Great Beauty remains potent, but it is outshined by its tendering of meanings that, with each carefully choreographed frame, appears to hint at a different kind of searching. The Church is just a pretext. In reality the show speculates on whether it is still possible to reveal God to contemporary man. The papal court, the curia and its con icts, remain in the background, though they provide the stage for the story, a space for suggestive dialogue, mostly monologues spoken by someone struggling to find answers within himself, someone still interested in ultimate. questions about existence—the end of being and the reason for being.

That is what fascinates me most about this production, which has invested capital and resources into a product that, were it not presented as a TV series, would no doubt be nominated for an Oscar, given the courage with which it outs convention by proposing the idea of God to a secular, positively pagan society.

Sorrentino’s hero is young but already world weary, a vicar of Christ robed in disquiet, a man of God one would think knew God better than anyone else who is actually wracked with more doubt than anyone else, a man who rises above his personality, the icon of an age dominated by image yet overwhelmed by decadence. Within the Church and—equally if not worse—outside its walls, there reigns a mediocrity af icted by the need to escape anonymity by every means and at all costs.

Sorrentino responds to questions about the meaning of life, history, the why and wherefore of injustice, pain and suffering, by feeding the pope words that belong to pioneers of reason, words be tting the great medieval thinkers who—wavering between heresy and dogma, between burnings at the stake and canonization— gave rise to free speech and noble ideas that once ushered in a new Europe, a new world.

This pope returns to speaking of God with painful probity and the shadow play of psychoanalysis, unwilling to sacri ce man’s intelligence or become a puppet, a caricature, but instead staying upright and not bending to servility, infantilism or mythic and superstitious superstructures.

Where is God? Where mercy? Where is man headed? The questions are time honored yet the novelty lies in restoring spiritual and intellectual inquiry to the center of the world and its destiny, without which—short of an answer, and a different kind of answer at that—the fate of the world is condemned to barbarism.

Such questions are frightening. They aren’t crowd pleasers. But thanks to the inventiveness of a cinematic genius they might nd a large audience once again. It takes courage to unseat the facile and convenient talk of a church that acts as a simple charitable organization only interested in performing good works and never saying why, that gets its hands dirty for the poor whom it often betrays yet doesn’t understand its choice.

Because in truth, talk of God and ultimate aims and the pursuit of thoughtful men might not even serve the purposes of the church. It’s no way to win audiences or sign clients. When newspapers report on the Pope or the church, they report on clerical organizations, ethics, scandals, travels and politics. Never God. Major papers cover Francis when he rebukes the elite or champions charities for the destitute, but why he does so, or what design animates him, is something we don’t know, take no interest in, fail to question.

Sorrentino points his camera on God to avow Him, deny Him, pursue Him, reject Him, invoke Him and curse Him. But God is still the star, and along with Him, man and his questions. That’s quite a feat to take on, and as far as I’m concerned, the director has already won.

To watch the Trailer >>>

* Gennaro Matino teaches Theology and History of Christianity in Naples. He collaborates extensively with both traditional and new media.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.