The Force Of Things - From Italy to New York and Back

The deeper one delves into Alexander Stille’s captivating The Force Of Things, the more tangible it becomes how sometimes the subject matter itself determines the tone and genre of a book. Ostensibly a memoir centered on his parents’ troubled relationship, the book merges biography, intellectual history and psychological portraiture, in a carefully calibrated prose at a novelistic pace.

The unlikely, often unhappy, enduring-against-all-odds, union of Mikhail “Misha” Kamenetzki, a.k.a Ugo Stille, a Jewish intellectual of Russian origin- with Elizabeth Bogert, a beautiful and restless Midwestern white Anglo-Saxon Protestant,allows the author to tackle from multiple perspectives a key element in the make up of contemporary American society: the “cross-pollination” (as Stille refers to it) which occurred as Jewish intellectuals in flight from Nazi-Fascist Europe entered the mainstream of American culture.

While much has been written about the impact of the German and Austrian Jewish intelligentsia that settled on the two American coasts after Hitler’s raise to power, the story of the much smaller (roughly 2800) Italian Jewish emigration remains largely unwritten.

The Kamenetzki family had fled Russia after the Bolshevik revolution, and after a brief residence in Germany arrived in Italy in the 1920’s. Mikhail (Michele) Kamenetzki grew up in Rome under Fascism. Italian language and culture were central to his education. He attended a prestigious Liceo Classico (where one of Mussolini’s sons was his classmate) and then enrolled at the University of Rome. In 1938, when the racial laws excluded Jews from all public schools, those who were already enrolled (as in Kamenetzki’s case), were allowed to finish. He graduated with honors from the University of Rome receiving praise from Giovanni Gentile, the author of the infamous “Manifesto of Fascist Intellectuals”.

Although his sympathies were from early on anti-Fascist, he remembered participating in uniform to the parades welcoming Hitler to Rome, where he and his best friend felt as “toy soldiers on parade”. As Italy entered the war and foreign Jews were sent to internment camps or confined to small villages, the family managed to obtain a visa to Portugal and passage to New York, despite the many roadblocks posed by both fascist authorities and the American Consulate, less than eager to allow Jews into the States.

In New York the Kamenetski’s settled first in Brooklyn and then on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. After Pearl Harbor, Kamenetzki joined the US Military, placing himself on the fast track for obtaining citizenship and seizing an opportunity to contribute to the fight against Nazi-Fascism. Like Peter Treves and a number of other recent Italian Jewish immigrants, Kamenetski joined the U.S. Intelligence, where thanks to his fluency in Italian he was assigned to the Psychological Warfare Branch. The now Sargent Michael Kamenetzki was shipped first to Algeria and - after the Allies’ landing in Sicily - in Palermo where he was in charge of setting up a radio station.

Before emigrating, Kamenetzki had shown precocious journalistic talent writing a column for the periodical Oggi, under the pseudonym Ugo Stille, which he alternately shared with his friend Giaime Pintor. Paradoxically, the racial laws that had forced him out of Italy, provided the big break in his journalistic career. In the immediate post-war years, Italy’s leading daily Il Corriere Della Sera had difficulty obtaining a visa for a correspondent; Kamenetzki/Stille, by then an American citizen, was uniquely positioned for an initially freelance job. This led to a protean forty-year career in that newspaper (which in itself deserves a separate book). In New York Ugo Stille frequented fellow Italian expatriates, among others Max Ascoli, Bruno Zevi, Nicola Chiaromonte and the future Nobel Prize winner Franco Modigliani. Through his work with Corriere Della Sera, he also quickly came into contact with the American political, financial and intellectual elites.

Anti-Semitism was an integral part of the background of Stille’s wife, Elizabeth Bogert. In rebellion against her own parents and the narrow mindness of her milieu, she came of age through contact with the (mainly Jewish) expatriates who attempted to recreate the new Bauhaus in Chicago. Interestingly, despite the fact that her first husband was also Jewish, when she re-married there was relief at her husband’s change of name from Kamenetzki to the less Jewish sounding Stille. Furthermore, in her only extramarital affair, she fell for Saul Steinberg, yet another European Jew who had arrived in New York after a formative period in Italy.

Misha and Elizabeth’s worlds collided in an explosive cocktail of attraction and disdain. Their daily conflicts deeply affected the upbringing of the author and his sister. As a result, a great deal of the author’s effort goes into a mixture of speculation and psychological insights into the mystery of what kept these two worlds together.

To Misha, Elizabeth represented the America he had come to love: “She had the freedom, naturalness, irreverent wit and beauty” of American actresses, “she had none of the layers of conventions and centuries of breeding that many European women had; she was genuine and direct”. And Elizabeth, while having little patience or understanding for Eastern European Jewish ancestry, was charmed by Misha’s intensity and conversational fireworks.

Despite an impressive amount of detailed research, Alexander Stille’s perspective necessarily remains that of a son, a scarred spectator to their ongoing conflicts. As Misha did not teach Italian to his wife and children, for many decades the family remained excluded from essential parts of his professional and social life.

The background for this tempestuous marriage is mid 20th Century New York, a time and place were individuals of diverging backgrounds could aspire to forge brand new identities for themselves.

Possibly the single greatest achievement of the book is the constant shift between the strictly personal and the collective: everything seems to occur on many distinct parallel planes.

While colorfully and painstakingly recording the specifics that made his parents exceptional individuals, Stille focuses on ways in which history, collective memory, a specific cultural climate, economic opportunity and random luck allow individuals to impact the world they live in. And conversely, on how historical events and cultural trends are ignited by individual actions and trajectories.

In a layered construction, the author conjures up a variety of group portraits that include his father’s anti-fascist circle in Rome, his mother’s party life in a Cornell sorority, the art and literary crowds they frequented in New York. There are also vivid reconstructions of the personalities and Weltanschaung of the two sets of grandparents and their universes. In these physical and psychological personas he builds up, the author places them within manifold literary and cinematic references. Among other, scenes from Middlemarch, The Great Gatsby, Candide, The Divine Comedy, Lady with the Lap Dog and Bunuel’s Exterminating Angel.

Unlike the majority of German and Austrian Jewish refugees who never returned to their countries of origin, most Italian expatriates returned to Italy in the post-war years. Ugo Stille, who had maintained a cultural umbilical cord with Italy through his work at the paper, was among the last to return when, in 1984, Corriere della Sera offered him the position of Editor in Chief.

Stille skillfully inserts himself into the narrative, alternating between the role of historian, investigative reporter and first person witness. In the shift between these roles, startling changes of perspective occur. For instance, when he uses his reporter’s skill to retrace from documents the movements across Europe of his paternal grandfather Ilya Israel Kamenetski, we are presented with a highly intelligent and wily man, equally at ease in Russia or in Naples, expertly manipulating the intricacies of Fascist bureaucracy. Among his startling-comical achievements he had managed to obtain a letter by the soldier-poet Gabriele D’Annunzio attesting to his services to D’Annunzio’s troupes during their short-lived occupation of Fiume.

This letter would later turn out to be providential in the family’s fate. The same man, through the eyes of the author as a young kid, was a “rumpled refugee moving slowly with the help of a cane”. And in the author’s mother words (over-medicated, shortly before dying) Ilya Kamenetzki is described as “a Yiddish-speaking shtetl Jew who had the instincts and manners of an itinerant peddler.”

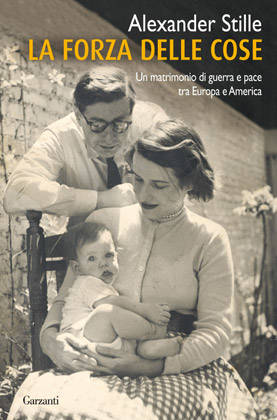

Next to the parade of characters who populate this book, the author pays close attention to material fragments that make up the fiber spun in weaving these lost worlds: scraps of paper, photographs, pieces of furniture, mental habits, turns of phrases each one a spring board for evoking an underlying world of unspoken emotion.

In the closing chapter of the book, Stille traces a sort of closing of the circle: after learning Italian and moving to Italy, he rediscovers the lost world of his father and embarks on his own adventure in journalism. As Ugo Stille spent decades explaining the US to Italian readers, in some generational symmetry, his son is now to scrutinizing facets of Italian society for American readers.

Alexander Stille’s first book, Benevolence and Betrayal was an attempt to presents the complex and diverse experience of Italian Jews under Fascism though the experiences of five families. In his latest one, while focusing and his parents’ marriage, he is also addressing large historical issues indispensible to understand contemporary American culture.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.