I write this blog with trepidation because I am reopening on the pages of i-Italy the controversy over MTV’s Jersey Shore -- a controversy that I wish could disappear. But after seeing the new Italian documentary Videocracy this weekend, it’s hard not to make the comparison between aspiring Italian-American reality TV stars and their aspiring paesani across the ocean.

Videocracy presents a well-known fact -- that Silvio Berlusconi, the Prime Minister of Italy, is also the President of TV, as filmmaker Erik Gandini repeatedly calls him.

Berlusconi controls ninety percent of Italy’s TV stations. Decades ago, Berlusconi realized how to better connect television and the people: one of his stations launched a quiz show in which every time a contestant got an answer right, an Italian woman would take off a piece of her clothing. And the rest is television history – Italy distinguishes itself by having some of the dumbest, raunchiest, and sexist television shows in the Western world. Videocracy documents the country’s obsession with TV and how the possibility of stardom (the American Idol phenomenon here) distracts a nation of people who are trapped in mediocre jobs with little chance of social mobility. That’s why thousands of girls line up from Italy’s tip to heel to try out to be a velina, a showgirl, who smiles and voluptuously shimmies next to a television host. In Berlusconi’s Italy that’s not too wacky a career choice since the Prime Minister (and the President of TV) hired an ex-velina to be in his cabinet.

The documentary is a grotesque portrayal of Italy under Berlusconi. By the time the audience sees a Berlusconi campaign commercial in which groups of Italians sing “thank God Silvio Berlusconi exists,” one begins to seriously fret about the future of Italian democracy. Indeed, it’s chilling to think about the message of Videocracy alongside that of Roberto Saviano’s brilliant book Gomorrah about organized crime’s control of the southern Italian economy.

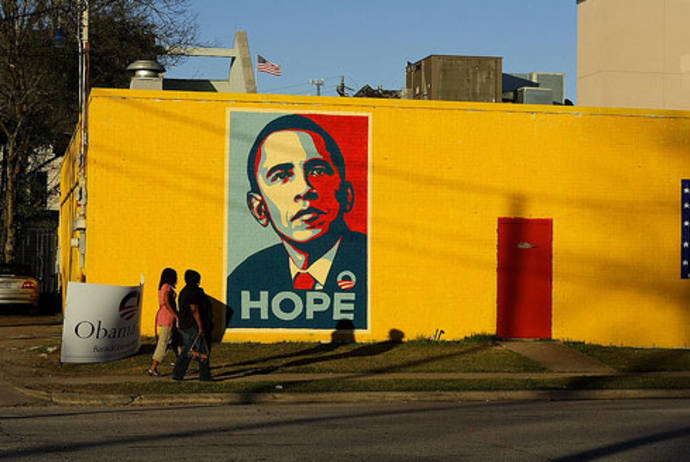

So why does this documentary remind viewers of the reality TV show Jersey Shore? Why does Time Out describe the documentary as "the Rosetta Stone by which we might come to understand Jersey Shore"?

What surprised me about the Italian-American outrage over Jersey Shore was the accusatory “they-did-this-to-us-again" mentality. Who is the “they” – all the Italian-Americans lining up to get a part on the show? The notion that the creators wouldn’t launch a similar show about African-Americans or Jews seems naïve in today’s land of reality TV – if money is to be made and people are willing, a show will be born. The kids who star in Jersey Shore have the right mix of fit bodies and sexual energy that television wants. If any other ethnic group meets the bill, they’ll get their own show too.

Videocracy shows how from the north to the south of Italy, everybody wants to get on TV, no matter how foolish they look (a woman with dyed red hair who looked to be in her sixties took her clothes off for a television audition, and it wasn’t a pretty picture). And who is the “they” doing this to them, insulting the image of Italians? None other than the prime minister of the country and the president of TV.

----

IFC Center

323 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY - (212) 924-7771

Videocracy

- 1hr 25min - Documentary - IMDb

10:45am 12:25 2:20 4:20 6:20 8:20 10:15pm