>> Visit the Parole ParoleYouTube channel to find all the currently available episodes.

*Stefano Albertini is the director of Casa Italiana Zerili Marimò at NYU,

>> Visit the Parole ParoleYouTube channel to find all the currently available episodes.

*Stefano Albertini is the director of Casa Italiana Zerili Marimò at NYU,

IN ITALIANO >>>

Pope Francis is a pope who, despite the strength of his sermons and his writing, prefers gestures to words: for his first trip outside the Vatican, he wanted to go to Lampedusa, where he celebrated mass in memory of the migrants who died. He used the wreckage of a boat as an altar and a cross made with two pieces of wood, which came from the same shipwreck. At the Holocaust Museum in Jerusalem, he kissed the hands of concentration camp survivors. He celebrated his first Coena Domini mass in a juvenile detention center, where he washed and kissed the feet of twelve detained youths, both boys and girls, two of whom were Muslim.

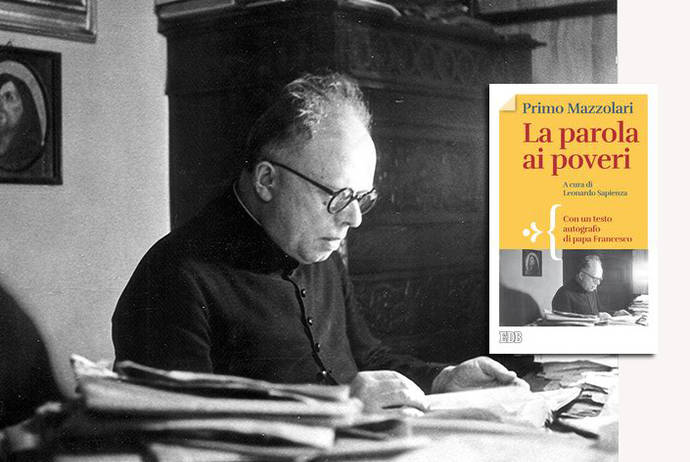

Even in remembering don Primo Mazzolari, Pope Francis’ gestures accompanied and underscored his words. A few months ago in Cremona, during the presentation of don Primo, La parola ai poveri curated by Monsignor Sapienza, the Pope handed the Bishop of Cremona a small blue box, which contained the so-called “Golden Rose” (coming from Francis, obviously it’s not actually gold) for don Primo’s tomb. It’s a highly symbolic gift that popes have been giving for over one-thousand years to leading Christians, cathedrals, and important Marian Shrines. For the first time, I believe, the precious rose wound up on the tomb of a country priest in a church within the village. But the most symbolic, effective, and memorable gesture on this journey to discover don Primo is definitely the Pope’s pilgrimage to Bozzolo, his silent prayer over the tomb of don Primo, and, later that same day, over that of don Lorenzo, two priests who in their times were considered “rebels,” “disobedient,” and “agitated.”

The sentiments of the Pope and don Primo regarding the poor are so clear that if you were to thumb through their written accounts on the subject at random, it would seem that they were written by the same person. The archbishop of Buenos Aires always made the poor an absolute priority even before becoming Pope and even before becoming familiar with don Primo. And I believe that it is reasonable to think that this discovery happened after becoming Pope. His associates remember that when Pope Francis was asked to preside over a Latin-American episcopate conference, they kept asking him if there was a mock-up for the conference. His response was simply “Jesus Christ and the poor.”

The Pope himself said that during the conclave while the votes were still being counted, but the quorum for his election had already been reached, his friend Claudio Hummes, a Brazilian (and Franciscan) cardinal, hugged him and whispered “don’t forget about the poor.”

He gave, and continues to give, unequivocal evidence in facts, more than in words, of wanting “a poor church for the poor.” However, this attention to the poor is not sentimental pauperism; it’s a radical and revolutionary change in perspective. In 1949 don Primo wrote “The destiny of the world develops in the suburbs.” This is the suburb where Bergoglio comes from. He believes it to be an existential locus more so than a geographic one.

Pope Francis’ ecumenism is under the eyes of the world. Even here, we see an ecumenism of gestures in addition to words; the embracing of orthodox patriarchs, the visits to both Lutheran and Evangelical churches, and the trip to Germany for the anniversary of the Reform have strengthened a reciprocal trust and has reopened a dialog that had lost steam during the last papacy.

Francesco’s ecumenism is, like the rest of his papacy, more pastoral than theological. When asked questions regarding existing doctrinal obstacles, he says that he prefers to leave that discussion “to the theologians. They know it better than we do. [...] What do we, as the people, need to do? Pray for one another. [...] And, second, we need to do things together: there are the poor; we work together with them; [...]; And the migrants? Let’s do something together with them…”

Don Primo’s ecumenism came from his heart and soul and was persecuted and punished. That’s why it’s still rare and precious even today. In 1934 his book La più bella avventura was published. It was a reflection on the Parable of the Prodigal Son. For Mazzolari, the older brother represented the conformist Catholic that struggles to understand God’s mercy and the church’s embrace of the prodigal brother.

The book was received favorably among Italian Evangelicals, and, as a consequence, it caused the first overreaction from the Holy Office toward the archpriest of Bozzolo. Even the bishop of Cremona, Cazzani, who tried to protect and defend don Primo from his prosecutors, was struggling to understand don Primo’s attitude and would scold him for his friendship with Ferreri, the Wesleyan pastor.

In comparing the Archpriest of Bozzolo to the Bishop of Rome, I didn’t want to invoke primogenitures, put quotations on the same level, and much less demonstrate the influence of one on the other. I only wanted to note the common sensibility of the two priests coming from the suburbs, who, at different moments in history, knew how to open the windows and doors of the Church to the spirit that constantly renews and transforms it.

Stefano Albertini is a professor of Italian literature and cinema at New York University and the director of NYU’s Casa Italiana Zerilli-Marimò.

Published in the special weekly “La Vita Cattolica” from the diocese of Cremona.

For more news and information:

La Voce di New York italian >>

La Voce di New York english >>

La Gazzetta di Mantova >>

La Repubblica >>

San Francesco >>

Pope Francis’ entire conversation in Bozzolo was published on Facebook by Don Antonio Spadaro

(Consultore at Pontificio Consiglio Della Cultura, Direttore Responsabile at La Civiltà Cattolica and Editor at La Civiltà Cattolica) >>

Papa Francesco è un Papa che, nonostante l’estrema efficacia della sua predicazione e dei suoi scritti preferisce i gesti alle parole: per il suo primo viaggio fuori dal Vaticano ha voluto andare a Lampedusa dove ha celebrato la Messa in suffragio dei migranti morti in mare usando il relitto di una barca come altare e una croce pastorale fatta di due pezzi di legno che venivano dallo stesso relitto; al museo dell’Olocausto a Gerusalemme ha baciato le mani dei sopravvissuti dei campi di sterminio; la sua prima Messa in Coena Domini l’ha celebrata in un carcere minorile dove ha lavato e baciato i piedi di dodici giovani detenuti, maschi e femmine, due dei quali musulmani.

Anche nel suo avvicinarsi a don Primo Mazzolari i gesti hanno accompagnato e sottolineato le parole. Qualche mese fa, in Comune a Cremona, durante la presentazione del libro di don Primo, La parola ai poveri curato da Monsignor Sapienza, lo stesso prelato ha porto al Vescovo di Cremona, tra la sorpresa generale, un cofanetto blu che conteneva la cosiddetta “rosa d’oro” (venendo da Francesco, ovviamente d’oro non è) per la tomba di don Primo, un dono altamente simbolico che i papi da più di mille anni fanno a principi cristiani, a cattedrali o importanti santuari mariani. Per la prima volta, credo, la preziosa rosa finisce sulla tomba di un prete di campagna in una chiesa di paese. Ma il gesto più simbolico, più efficace, più memorabile in questo cammino di scoperta di don Primo è senz’altro il pellegrinaggio del Papa a Bozzolo, la sua preghiera silenziosa sulla tomba di don Primo e, più tardi lo stesso giorno su quella di don Lorenzo, due preti ritenuti ai loro tempi ‘ribelli’, ‘disobbedienti’, ‘inquieti’.

La comunanza di sentire tra il Papa e don Primo riguardo ai poveri è così lampante che sfogliando anche a caso i loro scritti sul tema sembra che vengano dalla stessa mano. Certamente anche prima di conoscere don Primo, e credo sia ragionevole pensare che questa scoperta sia avvenuta dopo l’ascesa del card. Bergoglio al pontificato, l’arcivescovo di Buenos Aires aveva fatto dei poveri una sua priorità assoluta. Ricordano i suoi collaboratori che una volta incaricato di presiedere i lavori di una conferenza dell’episcopato latinoamericano a chi gli chiedeva insistentemente se ci fosse una bozza programmatica rispondeva solamente “Gesù Cristo e i poveri”.

Il Papa stesso ha raccontato che durante il conclave, mentre si contavano ancora i voti, ma si era già raggiunto il quorum per la sua elezione, il suo amico Claudio Hummes cardinale brasiliano (e francescano) abbracciandolo gli ha sussurrato “non dimenticarti dei poveri” e, una volta Papa.

Egli ha dato e continua a dare prova inequivocabile nei fatti ancora più che con le parole di volere “una chiesa povera per i poveri”. Per entrambi però l’attenzione ai poveri non è pauperismo sentimentale, ma è un radicale e rivoluzionario cambio di prospettiva: “i destini del mondo si maturano alla periferia” scriveva don Primo nel 1949, quella periferia del mondo dalla quale Bergoglio viene e che per lui è un locus esistenziale più che geografico.

L’ecumenismo di papa Francesco è sotto gli occhi del mondo; anche lì un ecumenismo di gesti, oltre che di parole: l’abbraccio coi patriarchi ortodossi e le visite alle chiese luterane ed evangeliche, il viaggio in Germania per l’anniversario della Riforma hanno rinsaldato una fiducia reciproca e riacceso un dialogo che si erano raffreddati durante il precedente pontificato.

L’ecumenismo di Francesco è, come tutto il suo pontificato del resto, più pastorale che teologico. Quando gli vengono rivolte domande sugli ostacoli dottrinali ancora esistenti risponde che preferisce lasciare quella discussione “ai teologi, loro sanno farlo meglio di noi. (…). Che cosa dobbiamo fare noi, il popolo? Pregare gli uni per gli altri. (…). E, secondo, fare cose insieme: ci sono i poveri, lavoriamo insieme con i poveri; (…); ci sono i migranti?, facciamo qualcosa insieme…”

L’ecumenismo di don Primo era uno slancio del cuore e dell’anima che fu perseguitato e punito e che proprio per questo è ancora più raro e prezioso. Nel 1934, esce il suo libro La più bella avventura, una meditazione attualizzante della parabola del figliuol prodigo. Il fratello maggiore rappresenta per Mazzolari il cattolico benpensante che fatica a capire la misericordia del Padre e il suo abbraccio al fratello dissipatore.

Il libro viene ricevuto favorevolmente negli ambienti evangelici italiani e scatena, di conseguenza, la prima sproporzionata reazione del Sant’Uffizio nei confronti dell’arciprete di Bozzolo. Anche il vescovo di Cremona, Cazzani, che cercò sempre di proteggere e difendere don Primo dai suoi accusatori, faticava a capire l’atteggiamento di don Primo e lo rimprovera per la sua amicizia col pastore wesleyano Ferreri.

Nell’accostare l’Arciprete di Bozzolo al Vescovo di Roma non ho voluto invocare primogeniture, mettere citazioni in parallelo, e molto meno dimostrare l’influenza dell’uno sull’altro. Ho voluto solo notare la comune sensibilità di due preti venuti dalle periferie che in momenti storici diversi hanno saputo aprire le porte e le finestre della Chiesa allo Spirito che costantemente la rinnova e la trasforma.

* Stefano Albertini, e' professore di letteratura italiana e cinema alla New York University, e direttore della Casa Italiana Zerilli Marimò (NYU)

Pubblicato sul numero speciale del settimanale diocesano di Cremona "La Vita Cattolica"

Per approfondimenti e cronaca:

La Voce di New York >>

La Gazzetta di Mantova >>

La Repubblica >>

San Francesco >>

Il discorso integrale di Papa Francesco a Bozzolo , pubblicato su Facebook da Don Antonio Spadaro

(Consultore at Pontificio Consiglio Della Cultura, Direttore Responsabile at La Civiltà Cattolica and Editor at La Civiltà Cattolica) >>

Conosco mons. Gennaro Matino non solo dai suoi libri e dai suoi articoli, ma ho la fortuna di averlo sentito predicare, discutere e averlo visto in azione pastorale tra i suoi fedeli e coi suoi confratelli, per tanti dei quali è stato maestro e continua ad essere guida. Conosco la sua fede e la sua apertura al mondo e se potessi scegliermi un parroco, lo vorrei proprio come lui. Ma leggendo il suo ultimo articolo su i-Italy (Voglio bene a papa Francesco, ma…) (vedi related articles a destra) mi sono trovato in disaccordo con lui.

Le prima critica di Monsignore a papa Francesco riguarda il fatto che le sue dichiarazioni pubbliche ed estemporanee (ad esempio sui divorziati risposati o sulle persone LGBTQ) non sono seguite da direttive e decreti chiari. È vero che sulla questione della comunione ai divorziati non c’è stata una modifica del codice di diritto canonico o del Catechismo della Chiesa Cattolica e che la Amoris Laetitia chiede ai singoli vescovi di impostare una prassi pastorale adatta alla loro diocesi e soprattutto a considerare le peculiarità di ciascun caso, ma non impone nessuna ‘svolta’. È una questione complessa al centro dei cosiddetti ‘dubia’ espressi pubblicamente dai cinque cardinali ribelli ultraconservatori (che in altri tempi sarebbero già stati spogliati della porpora e spediti a purgare i loro peccati in qualche certosa senza riscaldamento). Ma Francesco ha sempre detto che non era interessato a una ridefinizione teologica del matrimonio (che rimane uno e indissolubile), ma in una diversa prassi pastorale e su quella (e don Gennaro lo sa meglio di chiunque altro) non si legifera. Quella è basata sul rapporto con le persone, sulla conoscenza dei loro problemi e del loro percorso di fede. Francesco, praticamente, invita vescovi e preti a fare quello che don Gennaro fa da decenni: ascoltare, accogliere e dialogare con tutti e a basare la pratica dei sacramenti non sui canoni del codice, ma sulla Fede vera delle persone.

La seconda critica è relativa al linguaggio poco ‘delicato’ che il papa avrebbe usato in diverse occasioni. Ricordiamoci che l’italiano del Santo Padre non è l’italiano colto e raffinato dell’alta borghesia italiana da cui veniva papa Montini e nemmeno quello sintatticamente perfetto e algido delle aule universitarie da cui veniva papa Ratzinger. È l’italiano degli immigrati piemontesi imparato in cucina dall’amata nonna, è l’italiano familiare, quotidiano e colloquiale che Jorge Mario ha assorbito col latte materno.

Nella fattispecie, don Gennaro rimprovera al papa di aver definito la presunta Madonna di Medjugorie “postina”. Premesso che postina non è un'offesa, ma una degnissima e nobile professione, il Papa, senza scomunicare nessuno, ha detto semplicemente cosa pensa di queste presunte apparizioni, peraltro mai riconosciute dalla Chiesa. Su questa faccenda si sono espressi tutti, solo lui doveva tacere? Le responsabilità sul fenomeno (ma sarebbe il caso di dire ‘affare’ visto i miliardi che muove) Medjugorie sono dei preti e dei vescovi che hanno continuato ad organizzare pellegrinaggi nonostante la proibizione e gli inviti alla cautela da parte del Vaticano e delle conferenze episcopali. E se vogliamo proprio dirlo chiaramente, la responsabilità maggiore è stata dei predecessori di Francesco che non hanno avuto il coraggio di dire pubblicamente quello che tutte le commissioni che avevano incaricato di indagare avevano concluso e cioè che le presunte apparizioni sono bufale o, nel migliore dei casi, frutto di un fenomeno di autosuggestione collettiva. A recare scandalo alle nonnine che recitano il Rosario non è stato il “Madonna Postina” di papa Francesco, ma i preti e i frati che le hanno abbindolate inducendole a credere in quella bizzarra e non conclusa storia.

E permettetemi di concludere questo scambio di idee con don Gennaro con i versi di Dante che anche lui conosce ed ama:

Siate, Cristiani, a muovervi più gravi:

non siate come penna ad ogne vento,

e non crediate ch'ogne acqua vi lavi. 75

Avete il novo e ’l vecchio Testamento,

e ’l pastor de la Chiesa che vi guida;

questo vi basti a vostro salvamento.

(Paradiso V, 72-78)

Non so se papa Francesco abbia in mente questi versi, ma so di sicuro che a Dante un papa così sarebbe garbato. E parecchio.

Maria Chiara, Riccardo, Tao Massimo e Yang

Board Members of New York University and of Casa Italiana,

Friends and fans of our founder, welcome back home! Bentornati a Casa!

I have climbed these two steps to reach this podium almost every day of my life for the past twenty-one years, but today my legs feel heavy and my voice struggles to come out and, I know, will struggle even more as I try to share with you how the Baroness shaped not only the appearance of this building but also its substance and its soul. With Maria Chiara, during the days preceding the Baroness’s funeral, we were talking about how she lived at least three lives: a first one as a young girl growing up in Fascist Italy and in war-ridden Milan; a second as the wife and partner of one of the most prominent protagonists of the industrial reconstruction of Italy after WW2 and of the economic miracle that witnessed Italy's transition from one of the most impoverished European countries to one of the most industrialized nations in the world; and a third as the young widow who, after a period of deep sorrow and lack of motivation, found the strength to re-invent herself by crafting a new ‘persona’, and inventing a role that was rather unique if not completely unheard of especially for a woman and even more so for an Italian woman in an American context.

Regarding Mariuccia the child and the young girl, there is nothing we can add to Beyond these Walls, https://youtu.be/qKCQq-bwd08 a little jewel of a documentary that combines history and poetry and that could be subtitled ‘a story of two stubborn ladies' (one in front of the camera and one behind it). When approached by the producer Elizabeth Hemmerdinger, the Baroness was surprised and had doubts about shooting a documentary about herself: “who is going to care about what I did during the war? I was one of the millions of people affected by it, and not even in the most horrible way” she used to repeat to me. But the film did not have the ambition to unveil a new source on WW2 history, but more acutely to show how the war experience shaped and streghtened the personality of the young Mariuccia by giving her a sincere commitment and longing for peace and ultimately for dialogue, the only way in which wars can be avoided and peace can be achieved and maintained.

During her 'second' life, she lived by the side, and partly in the shadow, of the larger-than-life entrepreneur Guido Zerilli. All of you, I’m sure, heard her talk about her Guido on some occasion or another and you must have been as struck as I always was in hearing the same unchanging love, admiration and devotion coming from her whenever she talked about her late husband. By Guido’s side, she also started her social and diplomatic apprenticeship, rubbing elbows with industrialists, heads of states, and diplomats. She would always remember, among the daytime nightmares of that period, the small dinners at the Quirinale Palace, the residence of the President of the Italian Republic who, possibly encouraged by her young age and even younger appearance, never missed a chance to test her knowledge on Italian and European history. What was the name of the finance minister of a certain king, who succeeded some queen or another… But of that period, the Baroness always remembered the spirit that animated all Italians involved in the reconstruction effort; everybody wanted to put the country back on its feet: enterpreneurs, workers and politicians seemed - for a short while - to have overcome their differences in order to achieve a single strongly desired goal: the moral, economical and political rebirth of the motherland, la Patria, a word the Baroness was not ashamed to pronounce.

But most of us here, except her family, obviously, came to know only the 'third' Mariuccia, a woman who overcame the grief and sorrow for the loss of her husband by creating a brand new life for herself, driven by the desire to promote culture and the arts as fundamental parts of the dialogue between people of all nations. It is after Guido’s death that she finally was able to complete with great passion and - you can be sure - brilliant results, the college degree she hadn't completed as a young woman. Her beloved romance languages and literature, as well as European history, kept her company during many sleepless nights in Lausanne.

The foundation of this Casa was the pinnacle of her much larger and influential presence, especially here in New York, a city she loved from the first trip with her husband (on an ocean liner, of course) until she established her residence on Central Park South. She loved the fast pace of New York, she loved the no-nonsense attitude of newyorkers, she loved the never ending surprises that pop up at every corner, she loved the many layers of its relatively short history, and, of course, she absolutely loved its bustling and sparkling cultural and artistic life. When she had to choose the base for her third life, she had no doubts and chose New York, a city that embraced her and understood her.

Let me define her with five adjectives, only because I have to limit myself: She was MAGNIFICA, as Stefano Vaccara defined her in his article for La Voce di New York, and indeed her mecenatism had its roots in the Italian Renaissance. She was and remains an exception on the Italian scene, where many people with extraordinary patrimonies don't give anything to anybody. Her generosity was not an action, the action of donating something to a person or a cause; her generosity was a state of mind, a natural disposition of her kind heart, as so many people have reminded us these days. Her generosity was a tactful, graceful, and truly noble way to help people and causes.

She was PASSIONATE about the things she loved. And this place, her Casa, she loved very dearly. She did everything she could so it would not only be "named" Casa but also would "feel" like a home for the students, professors and members of the community who crossed its threshold. When she was in New York, she wouldn't miss a single event, and when she was here, she would graciously greet the people who came in and ask them about themselves and their families. She always said, and Maria Chiara is not jealous, that Casa was her other daughter, and we try every day to be faithful to the values that the Baroness taught us through her example more than with words: work hard, use resources intelligently and without squandering, always put that touch of elegance and class in everything we do.

She was strongly OPINIONATED and at the same time RESPECTFUL of all points of view. A short episode will help me explain her attitude in this regard: an Italian politician of the far left came to give a talk. The Baroness came, took her seat, listened to the whole speech, graciously greeted him, thanked him afterwards and went home. The morning after I was waiting, somehow anxiously, for her call, as she would normally call me every morning after an event she attended, to comment it together. “He is really brilliant -she started- he has the rhetorical skills of a Roman tribune and an excellent preparation” followed by a long pause and, while I was starting to feel relieved, she continued: “he is very dangerous”. I was silent and she suggested that now we should invite somebody from the right wing coalition to somehow counterbalance the very successful talk of the evening before. But her conclusion was: “who are we going to call? They are all so clumsy that they would damage their own cause”. We both had a good laugh and continued to talk about other plans for the Casa.

Not once in the twenty-plus years we worked together did she tell me “why did you invite so-and-so?” or “I don’t like that conference or the politics of that film”. Never. On the contrary, she was always and only constructive and a true explosion of ideas and suggestions; she would read the Italian paper Il Corriere della Sera every day from cover to cover and she would cut out articles and handwrite on them “Per Stefano. Could this be of interest for an event at the Casa?” and when she came over she would hand me these big overstuffed envelopes with clippings that very often really turned into events.

You will forgive me if I keep to myself what she meant to me personally, especially in the darkest moment of my life, but that alone to me is the proof of the adjective that defines her better than any other, the simple and sometimes overused GOOD. I want to close my remarks not with my words, but with the words of the poet Attilio Bertolucci from a short poem he wrote in 1929. I’ll read it in Italian and will not translate it. It is my farewell to the Baroness and my promise to her and all of you. Her absence from this home will be her more intense presence:

Assenza

Più acuta presenza.

Vago pensier di te

Vaghi ricordi

Turbano l’ora calma

E il dolce sole.

Dolente il petto

Ti porta,

Come una pietra

Leggera.

-----------

Traduzione in italiano

Familiari, parenti e amici della nostra fondatrice, bentornati a Casa!

Da 22 anni salgo praticamente ogni giorno questi due gradini per raggiungere questo podio, ma oggi le mie gambe sono pesanti e la mia voce fa fatica ad uscire e, lo so già, farà ancora più fatica mentre cercherò di raccontarvi come la Baronessa non ha solo determinato l’aspetto esteriore di questo edificio, ma anche la sua sostanza e, direi, la sua anima.

Con Maria Chiara, nei giorni precedenti il funerale della Baronessa ci dicevamo che aveva vissuto almeno tre vite: la prima da ragazzina nell’Italia fascista e nella Milano devastata dalla guerra; la seconda da moglie e ‘sodale’ di uno dei più importanti protagonisti della ricostruzione dell’Italia, dopo la fine del secondo conflitto mondiale e del miracolo economico che vide l’Italia passare da uno dei paesi più poveri d’Europa a una delle potenze più industrializzate del mondo; la terza da giovane vedova che, dopo un periodo di profonda tristezza e mancanza di motivazioni, trovò la forza di reinventarsi creando di fatto una nuova ‘persona’: un ruolo che era piuttosto unico, se non completamente inedito specialmente per una donna e ancora di più per una donna italiana in un contesto americano.

A proposito della Mariuccia ragazzina non possiamo aggiungere niente a quel piccolo gioiello che è Beyond these Walls, https://youtu.be/qKCQq-bwd08, un documentario che combina storia e poesia. Quando la produttrice del documentario, Elizabeth Hemmerdinger le propose il progetto, la Baronessa mi manifestò ripetutamente la sua perplessità e i suoi dubbi: “a chi può interessare quello che ho fatto io durante la guerra? Io ero solo uno dei milioni di persone toccate e nemmeno nella maniera più atroce”.

Ma il film non aveva la pretesa di svelare una nuova fonte della storia della seconda guerra mondiale, ma più acutamente, di mostrare come l’esperienza della guerra aveva formato e fortificato la personalità della giovane Mariuccia, dandole un sincero desiderio di pace e quindi una propensione per il dialogo, l’unico modo in cui le guerre possono essere evitate e la pace può essere ottenuta e mantenuta.

Durante la sua ‘seconda vita’, visse accanto e, in parte, all’ombra del marito, Guido Zerilli, straordinario imprenditore farmaceutico, ma anche giornalista e diplomatico. Tutti voi, ne sono sicuro, l’hanno sentita parlare del suo Guido in qualche occasione e credo che anche voi, come me, sarete stati colpiti dall’amore immutabile, dall’ammirazione e dalla devozione che trasparivano dalle sue parole tutte le volte che parlava del marito. Proprio accanto a Guido iniziò il suo apprendistato sociale e diplomatico.

Ricordava spesso tra gli incubi diurni di quel periodo le cene riservate al Quirinale, durante le quali il Presidente della Repubblica Einaudi, forse incoraggiato dalla sua giovane età e ancor più giovane apparenza, non perdeva occasione per interrogarla in storia italiana ed europea. Ma di quel periodo, la Baronessa ricordava soprattutto lo spirito che animava gli italiani coinvolti nella ricostruzione: tutti volevano rimettere in piedi il paese. Sembrava che, per un troppo breve periodo, imprenditori, lavoratori e politici avessero superato le loro differenze per raggiungere un unico agognato fine: la rinascita morale, economica e politica della Patria. Patria, una parola che la Baronessa usava senza timidezza.

Ma la maggior parte di noi, eccetto la sua famiglia, ovviamente, ha conosciuto solo la ‘terza’ Mariuccia, una donna che è riuscita a superare il dolore e l’angoscia per la perdita del marito, creando per sé una vita nuova, spinta dal desiderio di promuovere la cultura e le arti come parti fondamentali del dialogo tra popoli di tutte le nazioni. Fu infatti solo dopo la morte di Guido che riuscì a conseguire con grande passione e brillanti risultati la laurea che non aveva potuto completare da ragazza. Le sue amate lingue e letterature romanze e la storia europea le hanno fatto compagnia in tante notti insonni a Losanna. La fondazione di questa Casa è stata l’apice della sua ben più grande e influente presenza, specialmente qui a New York, una città che amò dal primo viaggio col marito in transatlantico negli anni ‘50 fino a quando stabilì la sua residenza su Central Park South. Le piaceva il ritmo veloce della città, si trovava a suo agio con l’atteggiamento pragmatico e poco cerimonioso dei newyorkesi, era affascinata dalle infinite sorprese che la città ti riserva praticamente a ogni angolo, era incuriosita dai molti strati della sua seppur breve storia, ma amava soprattutto la vivacità e l’originalità della scena artistica e culturale. Per tutte queste ragioni, quando si trattò di scegliere la base per la sua ‘terza vita’ non ebbe dubbi o esitazioni e scelse New York, una città che la capì e la abbracciò.

Vorrei ora limitarmi a cinque aggettivi per definirla. Era MAGNIFICA, come l’ha definita Stefano Vaccara nel suo articolo per La Voce di New York. E infatti il suo mecenatismo ha le sue radici nel Rinascimento italiano. Mariuccia Zerilli era e rimane un’eccezione sulla scena italiana, dove tantissime persone con patrimoni ingenti non danno niente a nessuno. La sua generosità non consisteva nell’azione di donare qualcosa a una persona o a una causa, la sua generosità era un tratto del suo carattere, una disposizione naturale del suo cuore buono, come tante persone mi ricordano costantemente. La sua generosità era discreta, direi elegante e veramente un modo nobile di aiutare persone e cause.

Era APPASSIONATA delle cose che amava. E questo lugo, la sua Casa lo amava in maniera tutta particolare. Fece tutto quanto era possibile affinché non fosse una Casa solo nel nome, ma affinché facesse sentire veramente ‘a casa’ gli studenti, i professori e chiunque attraversa la sua soglia. Quando era a New York non perdeva un evento e quando era qui salutava volentieri le persone che partecipavano e chiedeva a ciascuno di sé e della sua famiglia. La Baronessa diceva sempre, e Maria Chiara non è gelosa, che la Casa era la sua altra figlia e noi cerchiamo di essere fedeli ogni giorno ai valori che la Baronessa ci ha insegnato con l’esempio più che con le parole: lavorare sodo, usare le risorse in maniera intelligente e senza sprechi, mettere sempre un tocco di classe e di eleganza in ogni cosa che facciamo.

Era al tempo stesso OSTINATA, ma anche RISPETTOSA dei punti di vista altrui. Un breve episodio mi aiuterà a spiegare il suo atteggiamento a riguardo. Un politico italiano di estrema sinistra venne a fare una conferenza. La Baronessa venne a sentirlo, lo salutò molto gentilmente prima e lo ringraziò alla fine del suo intervento e poi tornò a casa. La mattina dopo aspettavo, anche con un po’ d’ansia, la sua telefonata, visto che normalmente mi chiamava sempre il giorno dopo un evento al quale aveva partecipato per commentarlo insieme. “È veramente brillante – esordì – ha le capacità retoriche di un tribuno romano e un’eccellente preparazione”. Seguì una lunga pausa e mentre io cominciavo a sentire un po’ di sollievo continuò: “È pericolosissimo!”. Io rimasi in silenzio e lei suggerì di invitare qualcuno della coalizione di centro-destra per controbilanciare il successo della conferenza della sera precedente. Ma dopo un’altra pausa di silenzio la sua conclusione fu: “ma chi invitiamo? Sono tutti così maldestri che finirebbero col danneggiare la loro stessa causa.” E così, chiuso il bilancio della sera prima con una risata continuammo a fare piani per la Casa.

Non una sola volta in più di vent’anni di collaborazione mi ha detto “perché ha invitato Tizio?” o “Non mi piace l’impostazione di quella conferenza o la linea politica di quel film”. Mai! Al contrario, era sempre e solo costruttiva e propositiva, una vera esplosione di idee e suggerimenti. Ovunque fosse nel mondo, leggeva Il Corriere della Sera ogni giorno da cima a fondo; ritagliava gli articoli che riteneva più importanti per noi e poi scriveva a matita un commento del tipo “Per Stefano. Potrebbe interessare per un evento alla Casa?” e quando arrivava nel mio ufficio la prima cosa che faceva era la consegna di queste buste strapiene di ritagli di giornale che spesso sono davvero diventate nostre iniziative.

Mi perdonerete se tengo per me quello che la Baronessa ha rappresentato per me personalmente, specialmente nel momento più oscuro della mia vita. Il ricordo del suo sostegno materno in quel momento giustifica per me l’attributo che la definisce meglio di qualunque altro: il semplice, e qualche volta inflazionato, BUONA.

Voglio chiudere questo mio ricordo non con le mie parole, ma con le parole del poeta Attilio Bertolucci da una breve poesia del 1929. È il mio addio alla Baronessa e la mia promessa a lei, alla sua famiglia e a tutti voi: la sua assenza da questa casa sarà in realtà una sua presenza più intensa.

Assenza

Più acuta presenza.

Vago pensier di te

Vaghi ricordi

Turbano l’ora calma

E il dolce sole.

Dolente il petto

Ti porta,

Come una pietra

Leggera.

---

Stefano Albertini is a native of Bozzolo in the Northern Italian province of Mantua studied at the Università di Parma, where he majored in Political History. After obtaining his M.A. in Italian Literature from the University of Virginia he was admitted to Stanford University where he earned his Ph.D. with a dissertation on the rethoric of violence in Niccolò Machiavelli’s writings.

He has published extensively on topics ranging from Dante to Renaissance Literature, to Church/State relations during fascism.

Since 1994, he has been teaching literature and cinema in the Department of Italian Studies at New York University. From 1995 to February 1998 he was Associate Director of Casa Italiana Zerilli-Marimò and since then he has served as Director.

Let’s start with your (clearly Sardinian) last name. Tell us about your origins, your education and training, what your cultural interests are.

I was born in the province of Iglesias in the 1950s. I studied in Cagliari and then at the University of Pisa. I got my start in France with the Hachette Group, specifically in the field of communications. Then I came to the United States where since the late 80s I’ve been helping my wife Nancy manage a real estate practice.

The main thing your acquaintances remark upon is your passion for

contemporary Italian art. A passion you share with your wife. How did that passion come about? Was there a specific turning point?

As a student in Florence the 1970s, I fell in love with contemporary art, especially after seeing a Paul Klee exhibit. Since then I started to pay attention to what was being made both in Italy and abroad. Meeting Nancy in New York has me often going back to Italy to see what is being done today. I have to say that contemporary artists in our country are truly exceptional. I became interested in them by collecting... In fact, we initially began collecting Murano glass.

So Murano glass marked the birth of your passion...

Once again I have to thank my wife, because she was the first to pick out Murano glass at an auction. Back then there were no real detailed catalogs of the works, so we started cataloguing everything made in Murano from 1910 to the 1990s. We discovered all these artists through that process, including Carlo Scarpa, who had worked intensely for Venini and eventually became its artistic director for many years. Then there was Gio’ Ponti and the great Massimo Vignelli, who has been of immense importance to us. He meant a lot to us. And to our cultural education.

Massimo was a friend, an instigator, a mentor, a brother, a father. He helped us design our first exhibit and my book Murano: Glass from the Olnick Spanu Collection, which served as a companion to our various shows in America. We had 12 shows in the US, one of which later traveled to Spazio Oberdan in Milan, a space designed by architect Gae Aulenti. From there the exhibit returned to the US and traveled to many institutions and museums, the last one at the Metropolitan Museum, which dedicated two shows to the collection: one to Carlo Scarpa and one to the architect Buzzi.

Your passion evolved from glass to encompassing contemporary Italian art in all its forms: sculpture, painting, installation. How did you develop that collection?

Initially it was a collection of American – and, naturally, European – art, which focused on the mid-90s up. It was the Arte Povera Group born in Turin, and a group of young artists, of which there are now ten, that helped us develop a program: the Olnick Spanu Art Program. It’s located in Garrison, about an hour from New York, close to our house. A property of around 370 acres.

We’ve established a program that allows an Italian artist to come live with us and create, develop and install a work of art on the property. It’s a very ambitious and beautiful project. A necessary one from the perspective of those who, like me, are focused on the diffusion of Italian culture in the United States.

We bought an old factory and decided to construct an adjacent building that will serve to house our collection as well as thematic exhibits featuring our young artists-in-residence. It will also function as a library, because we want all Italian art books to be here in the US and get translated. It’s important to facilitate knowledge so that Americans can grow increasingly close to our art. We would like it to become a center dedicated entirely to contemporary art from the second part of the 20th century in the United States.

Let’s talk about Casa Italiana. You’ve recently been elected – unanimously – to chair our board of directors. But your relationship to Casa goes way back. You’ve been on our board from the beginning.

Practically since Casa was born. I met the Baroness Mariuccia Zerilli-Marimo when I was looking for a school for my daughter Stella. We had decided to send her to the Scuola d’Italia “Guglielmo Marconi.” The baroness was on the school’s board. She asked me to become a part of Casa. I was especially fascinated by the Baroness herself: her manner, her strength, her drive to make Italian culture known. As you’re well aware, the French ruled over the European cultural landscape here in New York.

What new things should our board members, friends, and audiences expect from Casa?

I will expand programs relating to contemporary art, including painting and sculpture, and I would like for students as well as big art collectors to become better aware of what is happening in Italy now. I really want to make that message more widely known, bring it to every screen, render it visible everywhere.

Bring it to every screen – that’s interesting. Over the last few years Casa has tried to focus on all things pertaining to new technology, audio-visual apparatuses, video recordings… We’re the only entity in the US that records all of our programs and makes them available for free on the web. I’ve found in you an ally for these high-tech proposals. Like me, you believe that Casa is wonderful as is but that it’s also important for it to stretch beyond these walls.

Everything is done through screens today: whether it’s an iPhone, an iPad or a computer. What we’ve started doing – recording everything and uploading it online – is extraordinary, and we have to keep doing it. The website is great and easy to navigate but I’d like to see there be more things pertaining to contemporary art and our exhibits. The exhibitions organized by Isabella del Frate are all beautiful and interesting. We have to make them even more broadly known; their art must become increasingly accessible… in honor of our dear Baroness, who I think is following us closely and listening to us word by word...

Since 2015, Giorgio Van Straten has been the director of the Italian Cultural Institute on Park Avenue in New York. We’ve known each other for a long time, going back at least to 2000, when Giorgio won the Zerilli- Marimò Prize for Italian fiction with his memoir-novel Il mio nome a memoria

Giorgio Van Straten, despite his non- Italian name, is very Italian.

Yes, my family has Jewish-Dutch origins. My grandfather, who worked for a transportation insurance company, was transferred to an office in Genova. And there he ended up staying. So I am a second-generation Italian.

What’s the origin of your name? You spoke about this at length in your book.

It goes back to the French occupation of the Netherlands under Napoleon Bonaparte. Napoleon emancipated the Jews, who up until then had been discriminated against by law. He told Dutch Jews, “You need to chose last names for yourselves,” since in the early 1800s, living in a very closed world, they didn’t have or need last names. An ancestor of mine had to pick one, a very difficult choice indeed: it’s hard enough to choose your child’s first name, which only lasts a generation, while last names may last for hundreds of years!

Why “Van Straten?”

It means ”From the Streets.” Originally it had a double “a” (Straaten), but one “a” was dropped later for easier pronunciation in Italian. I was intrigued by this and wanted to retrace my family history beginning with this ancestor down through seven generations. Some things were already known, while others weren’t, or I discovered after writing the book ,when I was able to discover many more traces of relatives online, beyond traditional archival sources.

Now you are the Director of the Italian Cultural Institute. I think this is the first time a ”Culture Manager” was named to the post, someone experienced in managing cultural institutions. Your experience in Italy includes running prestigious cultural institutions, including the Palazzo delle Esposizioni, Scuderie del Quirinale, Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, and the Consiglio di Amministrazione della RAI. What do you bring from these experiences to your new position in New York?

I hope that this range of experiences can indeed be my contribution. I think that a Cultural Institute shouldn’t only endorse or focus on one aspect of culture over the others. If our job is to promote Italian culture, that obviously means promoting art, literature, cinema, theatre, and music. The larger issue is how to promote all of this well. First, I have the instrument, the Cultural Institute itself, which is above all a team of people with a mission, and then a building with its own physical limitations. Not all the events and programs that we have in mind can be held there. And there are some things that might best be held elsewhere, frankly... Let’s take art, for instance.

If I select a big, ambitious, and well-structured art exhibition, I’ll talk to the people who actually do such a thing. I’ll talk to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, to the Frick Collection, to the Museum of Modern Art to see if they may be interested. In my view, this is the goal of the Institute and we need to achieve it both by utilizing our own premises well and also by collaborating with other institutions that promote Italian culture in New York. We can do extraordinary things by working together, but if we all remain stuck in our own little worlds, our achievements are going to be much smaller.

It’s an interesting philosophy.

Well, I’m not here for self-promotion after all! I’m of a certain age and have accomplished things in my life; I don’t need to show off. But I’m not even here to promote just the Italian Cultural Institute. I am here to promote Italian culture.

Is there in your mind some aspect of our cultural heritage that we Italians haven’t done enough for? I mean, is there a sector of Italian culture that has been neglected or that needs stronger international promotion?

There is an aspect of our culture that is difficult to promote, and it is the part of culture that has to do with language. You see, art and music are media that can communicate universally, while language is peculiar to a specific culture. I believe that not everything we do has to be done in English, not always—and of course not everything needs to be done in Italian either. But if I invite Italian writers to present at the Italian Cultural Institute in New York, it would be a crime to force them to do it in English, even if their English is good, because their ”working tool” is the Italian language! Language is important and Italian, although a minority language, is also a very beautiful one, and we need to use it.

Another point of discussion and often a source of controversy is the relevance that Italian-American culture has for our institutions. In the past the Italian Cutural Institute used to consider it a separate matter, not worthy of attention. Casa Italiana, because of the direction set down by our late founder Baronesssa Zerilli-Marimò, has always been inclusive, open to promoting a sense of Italian culture that can include Italian-American culture. What are your thoughts?

Italian American culture belongs to both Italian and American cultures, and this is what makes it interesting. It would be a mistake however to think that the Italian-American community or the most recent communities of Italians who have immigrated to live and work here are my primary interlocutors—because our goal is to promote the Italian and Italian-American cultures among Americans at large.

I understand that this was to be a conversation, but I ended up giving you the third degree. Now, to be fair, it’s your turn to ask me a question, about anything you want.

Well, here you go. If you were to offer me a piece of advice—and I think you well-suited for this, as you know this city infinitely better than I do—what would you say?

On many topics I think we see things in a very similar way. One of the goals that I’ve lately been trying to work on— and this could be perhaps a common objective—is to take advantage of this great interest that there is in our culture, and try to go beyond what the Americans already know about Italy. This is what I think our challenge should be. There is a whole culture in contemporary Italy, a culture that belongs to the Italians who immigrated in recent decades, but one that is not well known. There is an extraordinary culture of comics, for instance, that an American would not immediately associate with Italy. These may become areas to invest on. One of our strategies should be to take advantage of what Americans already know about Italy, those Italian things that fascinate them, and push them a little further, towards aspects of our culture that are less known and less obviously linked to their idea of Italy.

I think this is a great idea.

Thank you!

*Professor Stefano Albertini is the director of Casa Italiana Zerilli-Marimò (NYU)

I have heard people refer to “colonial cinema” but there is no other book that mentions “empire cinema.” Why did you choose that term as the title of your book?

Because I wanted to bring attention to the dramatic period from the invasion of Ethiopia in

1935 until the fall of the empire, a period marked by the militarization of society and propaganda. The state supported cinema and spawned this body of work. So I wanted to set it apart from the colonial cinema of the pre-empire period.

Was Mussolini very interested in cinema? Did he have direct control over the directors?

At the beginning of the regime Mussolini was not interested in entertainment movies. He founded the “Istituto Luce” for documentaries and newsreels. Gradually, he realized that this was a mistake.

Was the popularity of foreign films an object of concern to Mussolini? And could this be why he supported the production of empire cinema?

Well, Italians didn’t really want to see Italian films as much as American or even French ones. So, after the invasion of Ethiopia, the Fascist state reorganized the cultural bureaucracy, founded Cinecittà, and gave Istituto Luce a new home to combat American cinema. They took distribution away from American studios. And, in retaliation, American films withdrew from the Italian market. This had a rather ambivalent reception: some worried about not having enough Italian production.

Your book states that 91% of Italian entertainment at that time consisted in going to see movies. So not being able to produce enough was a legitimate concern.

But eventually, during WWII, Italian cinema backed by the state became very successful and was one of the best selling across the axis block. But they had to get rid of American films from Italian screens to achieve that.

In your book you also mention that there are other examples of empire cinema. What would you say is specifically Italian?

There is a lot of foreign influence in these fascist propaganda films. But there are certain things that make them more Italian, like the fact that women are seldom on screen, even when there is a love interest.

The focus is on male bonding, the “military ethos.” Then there are films about emigration, the great drama of early 20th-century Italy, the loss of millions of Italians abroad. Declaring itself an empire gave Italians a chance to leave Brooklyn and Buenos Aires, and come home, not to Italy, where there was no work, but to the colonies.

Which of these films was more surprising or challenging to you?

I would say the two films shot in Somalia, about which nothing is written. One, by Romolo Marcellini, featured real soldiers and very few actors. The other, called Giungla Nera, starred a French actor who made both the Italian and the French versions of the film and a Somali woman. These films are a mix of documentary and fiction with subplots of love and war.

You underline the fact that in empire movies the line between documentary and feature films is blurred.

One of the things I argue in my book is that empire films became a site for experimentation. Because you have to show the colonies, you want to convince people that Italy is making them flourish. So there was a lot of emphasis on getting direct footage, sure, but also on emphasizing the glory of the Italian military by showing real soldiers.

Two generations of important Italian directors worked on these films, including people like Genini, Alessandrini and Cameroni, and also Fellini, Rossellini and Antonioni. But afterward these films were not remembered. Very rarely did directors speak about them, and this cinema was put into the closet.

Finding the material for this book was not easy. For instance, I realized that one of the four storylines of a 1942’s Benghazi had been removed by the Christian Democrats after the war because it featured a prostitute. So I wrote to the archivists at the Museo Nazionale di Torino, and they heroically managed to find a copy of the complete film.

You’ve mentioned that this novel is part of a ten-volume series. Was this project born this way? Or is it a decision that came with time?

Actually, it wasn’t born this way. I wrote the first book of the series called L’America non esiste (America Doesn’t Exist) four years ago. Then, when I wrote the second book Casa sulla roccia (House on the Rock) I realized that I liked having a recurring character. And then I thought of making this a multi-volume saga. The character of Ota Benga is tied to both the previous volumes and the project is to have ten volumes on twentieth century New York with recurring characters and also a few recurring jokes.

Definitely, the city of New York is what ties all these books together. It’s yourpersonal love statement to the city that you chose as yours and you have loved continuously.

New York is my stepmother. She welcomed me twenty-one years ago. And, unlike many other experiences in my life, New York kept its promises. Whatever she promised has arrived in a way or another. I’m not saying that it isn’t tough living here, but I still feel the same excitement, the same enchantment of day one. Yes, this is a love letter to this city.

And it’s a city that obviously changed immensely through the decades of the twentieth century. Let’s talk about the decade of Ota Benga: roughly the first fifteen years of the century. And tell us briefly about this character who gives the name tothebook.Yourotherbooks don’t get their names from their main character. In this case, you decided to give central stage to this person, a real person who truly existed. And perhaps we should mention that you always mix fictional characters with historical events, figures, and backgrounds. So who was Ota Benga?

First of all let me tell you that the best compliment my books have gotten so far was written in an Italian newspaper and said “this book reminds us of Wizard of Oz novels”. Of course, I don’t want to compare myself to the Wizard of Oz but there is something similar: the idea of putting together history with the small stories of some tiny made up characters. In this case, Ota Benga really existed. He was a pigmy from Congo, part of the Mutu pygmy tribe, who was kidnapped by slave merchants and sold to America to be exhibited in the world’s fair in 1904 in St.Louis. He was exposed alongside the great warrior Geronimo, with whom he became friends. But this is only the beginning of his tragic adventure because a few years later he was exposed in another exhibition in the Bronx Zoo, in 1906. The so-called “scientific” point of this exhibition was to “demonstrate” that this pigmy, being very short, was the missing link between monkeys and humans.

And this touches upon the central theme of the book: that is the confrontation of science and spirituality in the modernizing city of New York. And this type of science was so inclined to use some human beings as specimen, as things to be exhibited in museums or zoos, while on the other side there were a series of ministers, of clergy members who protested, arguing that these were human beings, and bringing up ethical issues focused around what constitutes a human being.

First of all, thanks for explaining the theme of the book so well. One of my main interests is in fact to show readers that when science - in this case distorted science or pseudo-science - becomes an icon, it loses the notion of empathy, of mercy, and creates monstrosities like this one. How can you show a human being in a cage alongside orangutans and chimpanzees? This poor man, who was still very young when he was kidnapped, suffered tremendously, not

only because his family was slaughtered, but because he was treated like an animal and no person should ever be considered an animal. And worse of all, this was done for the purpose of science, setting this case apart from many others like the one of the elephant man and of all the people who were part of freak shows all around the world.

And there’s a strong racial component here also.

Absolutely. And it’s interesting to note that the creator of this“scientific” exhibition was a man named Madison Grant, extremely famous at the time. If you google him, you will find lots of information. He did many good things for the environment, he loved animals, but he was a racist. He was convinced of the scientific truth of this project. In 1915 he wrote a bestseller entitled The Passing of the Great Race and by “great race” he meant the “Aryan” race, the Nordic white race. He was a racist, he hated Africans, African-Americans, Jews, Latinos. And his book was the primary inspiration for Hitler’s Mein Kampf. Even more disturbing is that a pupil of his became close friends with Heinrich Himmler and discussed genetics at length with him. This shows how distorted scientific ideas can lead to Nazism, genocide and horror.

Now let’s talk a little about the character you created. So far you’ve talked about the background characters, who have mostly negative, but important roles, that touch upon extremely important issues, so much so that they capture the attention of the reader. But let’s remember that this is also a novel, one about a boy and a girl.

Yes, the “real” protagonist is a young woman called Arianna Salis. She’s a fictional character, a young woman of Greek origin, who’s trying to understand who she is. She wants to be independent and studies anthropology at a time when that was really revolutionary. In the New York of the early twentieth century, for a young woman of Greek origin was not easy to travel the road of emancipation. Arianna finds work in the Bronx Zoo just at the time when Ota Benga is brought there to live with the orangutans and the chimpanzees. Arianna is in crisis before this affair, also because one of the organizers is her boyfriend. Here she starts a journey that leads her across the U.S. and beyond, while intertwining with Ota Benga a silent distance dialogue. In the end she will discover that the greatest treasure in life is not intended for those who have eyes full of certainties, but to those who know how to cultivate the doubt and research.

When in 1939 Pope Pius XII granted Italy two Patron Saints—Saint Francis of Assisi and Saint Catherine of Siena—he solemnly declared that St. Francis was “the most Italian of all saints and the saintliest of all Italians.

Whereas the second part of that statement is pretty obvious, despite fierce competition in theland “of poets, saints and navigators,” the second part always made me think about what made him characteristically Italian. What was it? His deep humanity, his cheerfulness, his love of nature, his untiring desire for peace? These are all beautiful traits of his personality, but the Italians hardly have a monopoly on them.

The most Italian of all saints

As I discovered in my second year of high school, what makes him so Italian is that he is the author of the first poem in the Italian language: The Canticle of Creatures. And for a nation that for about six centuries was only unified by its literature, being the founder of its poetic tradition is quite a big deal. I recognized the canticle from the modernized versions they had us sing in church as children, but the original was a different story. I could understand almost every word, but it was not the language I spoke with my friends or even in school. It had the arcane beauty of sounds and expressions that partly disappeared with time and partly typified the Umbrian vernacular that Francis spoke.

A solemn, yet joyful book of prayers

The canticle is a poem and a prayer (for some critics a prayer doesn’t count as a poem, but that escapes my understanding), a solemn yet joyful prayer of praise to God, the Creator for and from all creatures. Creatures that Francis calls, with moving confidence, ‘brother’ and ‘sister,’ as if he were extending Christ’s message of brotherly love outside its human boundaries. Each creature is defined with a perfectly equal number of adjectives (four adjectives each for the four fundamental elements, etc.) that aim to recreate in the poem the sublime harmony of creation. And each adjective is simple yet fitting: (Brother Sun is “beautiful and playful and robust and strong”(bello et iocundo et robustoso et forte). Sister water is “very useful and humble and precious and chaste” (multo utile et humile et pretiosa et casta). Wouldn’t you feel silly adding a single adjective to Francis’ description?

Francis’ multifaceted legacy

Francis even goes so far as to call death his sister. He probably felt its presence keenly while writing the canticle. He was likely quite sick at the time, weakened by fasting and penitence, and only a couple of years away from dying. But, as we know, death would not stop Francis’ brave and revolutionary march; his legacy is alive and well, despite the quarrels among his closest followers that led them to splinter off into dozens of different orders and congregations.

I see Francis’ presence in the environmentalist movement. I see his signature in every honest and courageous negotiation for peace. I see his style in every effort to bring people of different religions to a frank and open dialogue. And of course I contemplate much of Francis’ teaching in the words and actions of the first Pope who took his name.

But I like to think first and foremost that the Italian language is also one of his most precious legacies, a language that has his seal of approval and his blessing. He was our first poet, one of the founding fathers of our literary language, and every Italian poets and writer who has come after him is in his debt. Even the lofty, the aristocratic and the atheistic follow in the literary footsteps of the poor beggar from Assisi.