Augustus Bimillennary: Now, his Palatine palazzo is reborn

ROME – The Eternal City’s celebration of the second millennium of the death of Augustus in that month that takes his name proceeded this week with the formal opening to visitors of newly restored rooms in his palace and of the stunningly renovated Palatine Museum. Augustus was the emperor who famously said, according to Suetonius, “I found Rome a city of bricks and left it a city of marble.” The empire was taking profit from its expansion, but, in addition, new marble quarries had only then been discovered at Luna, near today’s Carrara, on the Italian coast.

In a curious way the dozens of experts who have beavered away on the Palatine for the past two years, and spent the relatively modest sum of $3.2 million of public money, have done something of the same: the team found an inchoate mass of ruins and left them vastly improved. The Palatine is an area of extraordinary importance, but for most of us who are not classicists, its ruins have been a tough read, until now.

The Palatine was inhabited well before 1000 BC, and archaeologists have excavated traces of its bronze age huts plus the famous dwelling of the first king of Rome, Romulus, traditionally dated to around 750 BC. The Palatine’s prehistoric aspect is reproduced in a model inside the museum, at the same time newly outfitted with up-to-date video aids to understanding, including a short film on the life of Augustus.

The five halls of the museum cover the origins of Rome, with tools, pottery and utensils from prehistoric times; the period from the early monarchy under Etruscan kings to the dawn of the Republic; the era of the Republic itself, when the Palatine Hill became the residence of the Roman hierarchs with their expanding military reach; and, finally, the Augustan era, when his palace stood on the Palatine. (That word, of course, comes from the name Mons Palatinus, the centerpiece of the famous seven hills of Rome overlooking the Roman Forum on one side and, on the other, the Circus Maximus.)

The museum offers a broad collection of findings from all over the Palatine Hill and reflecting its various eras. Augustus placed himself under the protection of the god Apollo, and frescoes from the Apollo sanctuary on the Palatine are among the treasures on view. Some of the tiny votive offerings to Roman deities date from the Republican era but, from around the Third Century AD, comes a singular anti-Christian graffiti panel showing a Cross topped by the head of a donkey and, below it, insults to those early believers in Christ.

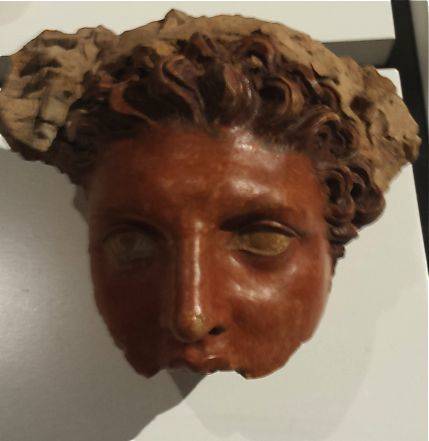

Under Augustus the style was dominated by things Greek – caryatids, decorative motifs on walls – because, scholars tell us, they reflected his propagandistic desire to be identified with the Golden Age of Athens under Pericles. Among the masterpieces therefore are fine white marble sculptures of a newly restored Aphrodite – on view for the first time ever – and of a life-sized nymph seated upon a rock. In another first, finely carved marble wings are on view, discovered only in 2011 in the House of Tiberius. And there are also dozens of strictly Roman realistic portraits in terra cotta and stone of emperors (one is Nero), of soldiers, solid citizens, little children, and one that looks like a cheery, busybody housewife.

Visitors can also access for the first time not only the House of Augustus, and see through a glass panel the famous, perfect “Studiolo” (Little Study) of the emperor and his reception rooms with their fine polychrome marble flooring, but also the House of Livia, with its frescoed walls. The emperor’s house and that of his beloved wife Livia were divided by the temple to Apollo (not preserved).

The number of viewers into the House of Augustus proper is limited, but reservations can be made by telephone: +39 06 3996 7700

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.