Being Leonardo Da Vinci: The Real Life of an Italian Genius

ll “We urgently need a science that honors and respects the unity of all life, recognizes the fundamental interdependence of all natural phenomena, and reconnects us with the living Earth. What we need today is exactly the kind of science Leonardo da Vinci anticipated and outlined 500 years ago, at the end of the Renaissance and the dawn of modern science.” So said one of my dear friends, Berkeley physicist Fritjof Capra, and it’s a statement I can get behind.

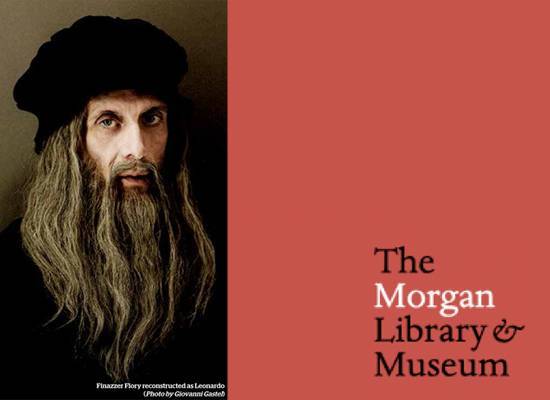

My performance, “Being Leonardo da Vinci,” depicts the real life of the Italian genius by bringing art history, science and contemporary dance to the stage. The show takes the form of an “impossible” interview, in which I physically become Leonardo, wearing period costumes and reconstructive makeup to render a true likeness of the genius, and reconstruct his Renaissance idiom; the text is culled from Leonardo’s own works, including his famous Treatise on Painting. Such a challenging performance has never before been attempted. “My” Leonardo answers 52 questions in the guise of philosopher, scientist, painter, inventor, architect, geologist, botanist and doctor. Leonardo, after all, encompasses everything, and to answer the question “Who is Leonardo?” we may concentrate on the painter, but we have to understand that without Leonardo the scientist, there is no Leonardo the man. The 52 questions touch on his childhood, his dreams, his civic and military work, how one becomes a “good painter,” and the relationship between science and painting, sculpture and painting, and music and painting. Leonardo holds forth on anatomy, experience and nature. He comments on the apostles in The Last Supper, discusses his passion for and obsession with water, argues for the primacy of sight as the most important of our senses, alludes to the fashion of his day, responds to his enemies’ attacks, explains the motions of the soul, prophesies human flight and, finally, dispenses aphorisms and advice on how to live in this day and age…

Years ago Mario Pomilio wrote: “I always believed deeply in the artist who talks about himself; and that, indeed, the best re-readings of a text occur each time we succeed in revisiting the world the author intended. The more I must believe in Leonardo, who proved so aware [of his own intended world] as to leave us not the first treatise of painting, but rather the first, in a modern sense, ‘poetry’ that no artist had hitherto attempted to conceive.” These words led me to believe that an imaginary interview is the one appropriate mise-en-scène that can capture the relationship between memory and the imagination. Only an interview allows Leonardo to address the pressing questions of our day and age, turning the theater into a place in which we can experience his way of thinking, his notion of a universal culture. Because the theater is the place where truth is overheard. We’ve all seen the works of Leonardo, but none of us has stopped to listen to him speak.

His real features, the gestures and gazes that have been carefully studied so as to give us a familiar image of Leonardo, help recreate a profile shrouded in mystery. The stark, deliberate contrast with a contemporary image of the interviewer underscores the revolutionary cast of Leonardo’s mind.

And the contemporary dance, choreographed by Michela Lucenti and performed by two dancers, is inspired by one of Leonardo’s most celebrated drawings, The Vitruvian Man, drawn around 1490 and currently kept in the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice. In an extraordinarily harmonious blend of space and movement, the two dancers bring to life a rich and highly technical dance, almost scientifically replicating Leonardo’s anthropomorphic model.

Da Vinci, the great genius of the Renaissance, has been the subject of hundreds of books, both popular and academic. Capra has written about him well, yet there remain few books about Leonardo’s science. To appreciate the range of his genius, we must understand the evolution of his thought and how it is linked to various disciplines. Art helped Leonardo advance his persistent explorations of life’s secrets. Leonardian synthesis is a synthesis of art, science and design, and in each area he sees nature as a guide and model. Yet Leonardo understood perfectly well that in the end, nature and the origins of life would remain a mystery. As art historian Kenneth Clark writes, “Mystery for Leonardo was a shadow, a smile, and a finger pointing into darkness.”

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.