Tony Scott. This is the Story of the Italian-American God of the Clarinet

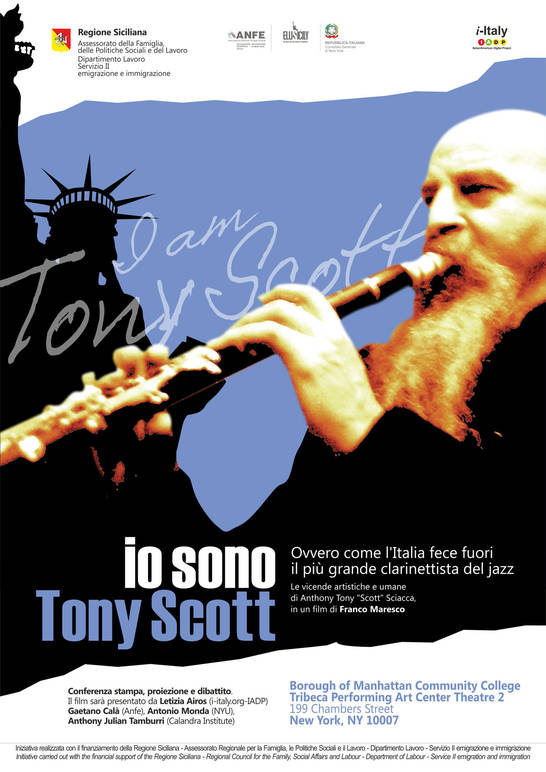

I met Franco Maresco for the first time, a little over a year ago in Palermo. They told me he had made an important Italian-American film, Tony Scott, ovvero come l’Italia fece fuori il più grande clarinettista del jazz [I am Tony Scott: How Italy Got Rid of the Greatest Jazz Clarinetist].

I knew him as a Sicilan director, screenwriter, and director of photography for sketches on Cynical TV and other documentaries, which were often very provocative. Knowing his attention was focused on an Italian-American story made me very curious. Why had he made a documentary about Tony Scott, actually Anthony Joseph Sciacca?

I enter and inside his office I immediately notice an indescribable amount of material collected to make the documentary. While speaking to Maresco, one of his associates played some film, mostly footage that was not used in the final cut. Beautiful, moving, almost always in black and white. And so disucssing the film, the director slowly loses his initial detachment and allows himself to share some special memories.

I saw Maresco’s film along with Gaetano Calà from ANFE. It was clear to both of us that we had to screen the film in New York City. This was made possible thanks to the work of the Calandra Institute and ANFE, and the film will be screened on October 2 at 6:00 p.m. at Borough of Manhattan Community College.

And so I began to discuss the documentary. What follows are responses to questions that I asked in a recent interview with the filmmaker, when he had just received confirmation that the film would be shown in New York City.

Tony Scott, ovvero come l’Italia fece fuori il più grande clarinettista del jazz [I am Tony Scott: How Italy Got Rid of the Greatest Jazz Clarinetist]. The title contains a sense of contradiction. How? Why? A country that doesn’t appreciate the greatest jazz clarinetist?

The interview with Maresco begins with my own curiosity: “Italy has erased Tony Scott with the weapon it knows how to use best: underestimation and indifference. Italy did not have it in for Tony, but it does have this attitude towards its most distinguished artists. This isn’t the case if there were a prize, the Riccardo Bacchelli prize, for example, which is awarded to artists who are living on the edge of poverty. Italy, alas, is a country that has a short memory and it’s not hard to imagine that someone like Tony, eccentric and bizarre, eventually became a sort of clown and was then marginalized by keeping his artistic greatness quiet.”

The idea caught on many years ago when, along with screenwriter Claudia Uzzo, Maresco decided to make a film about musicians of Sicilian origin who emigrated to America. They began researching and found that in Italy there lived a great musician, Tony Scott. In 2000 he was invited to play in Palermo and they shot a long interview at his residence in Rome. Much of this conversation was used in the film.

But it is the death of Tony Scott as an artist, forgotten by nearly everyone, which inspired Maresco to make a movie about him. “It was 2007 when I heard the news that Tony was dead. Something moved in my soul, a strong instinct that led me to take out the old interview and start making the film. Between research, preparation, and review, the project took almost three years.”

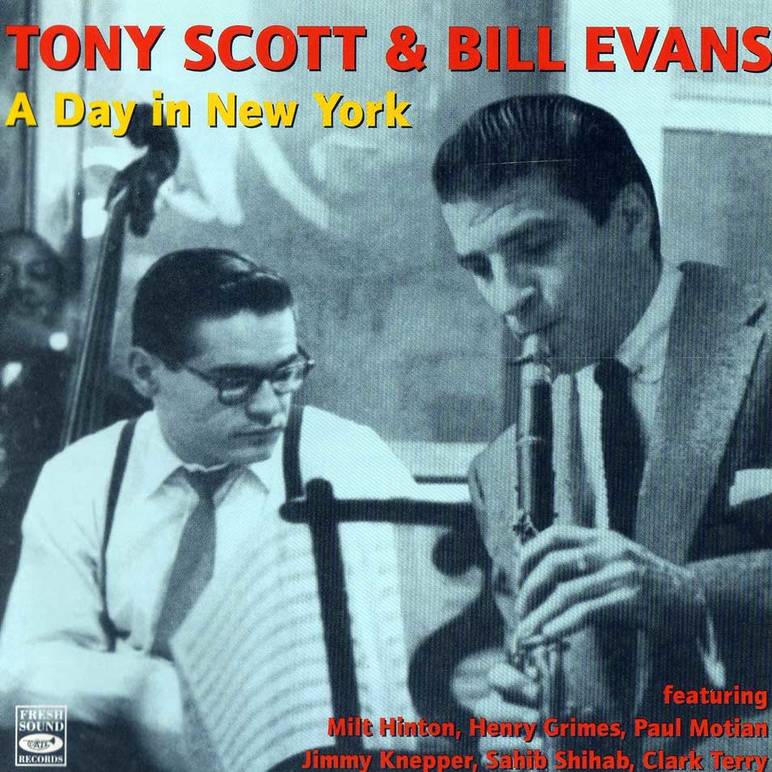

Tony Scott enjoyed great success in New York City between 1930 and 1950 when he was considered a god of the clarinet, but later led a humiliating life in Italy. Back in his homeland, he was crushed by tedious nights spent on TV, in the streets, in second-rate clubs. He died forgotten.

To make this documentary a reality, Maresco moved heaven and earth. His research spanned an ocean in 360 degrees. “We had to go back in time, to Tony’s birth in 1921 and his work as a musician from an early age. We went through the swing era and the 1950s with bebop, which were the happiest years of Tony’s artistic career. To help with the research we enlisted friends who are musicologists, especially Stefano Zenni, critics, musicians, and historians. We also investigated the history of migration, the history of the Sicilians in America, and the relationship between entertainment, music, and the mafia.”

It was certainly a challenge for the director, but he also knew what to look for. “I must say that I had some familiarity with the subject because I’m a jazz fan and so I had to know about the major contribution to jazz music that Italians made from the beginning. The two souths, the southern United States and southern Italy, join at the turn of the century and together they create this wonderful music that is jazz. This film debunks a number of misconceptions and highlights the importance that all have contributed something to jazz; Italians in general and Sicilians in particular have made a great contribution.”

And Scott was born in Salemi. Italians were not loved by the Americans back then. I ask what his research revealed. “There were so many stories and I regret not being able to keep them all in the film. For the sake of editing we had to cut a lot of things, including a part about the relationship between Sicily and the American Cosa Nostra, and the price that thousands of honest emigrants had to pay, shouldering the reputation as mafiosi, dagos, criminals. In the film there are many interviews with musicians and scholars on one hand and Tony on the other; when he was alive, he told me about the difficulties that Italian-Americans and southern in particular encountered in everyday life.”

And there was the mafia…. “This is a story that goes deeper and affects not only Italians. Even more mainstream films tell us this. Music was an essential element because the mob ran brothels and illegal gambling dens, and entertainment has always been a big business. On other occasions I’ve always said that, paradoxically, the mafia has made a significant contribution in supporting jazz and therefore the development of jazz music.”

The film is full of ideas. The personality of Tony Scott is extremely varied as is the historical period of his life. His relationship with Blacks, the battles for civil and human rights–he was a major supporter and this is recounted with great sensitivity in the film:

“This is one of the most fascinating aspects of Tony’s persona. I loved Tony and still love him as a musician and as a person because Tony was a Don Quixote, an true idealist. At the height of discrimination, Tony was also a great champion and defender of civil rights like few others.”

The story of Tony’s sad decline after his return to Italy for Maresco also becomes a way to describe a country that knows how to destroy itself. “The film is not just for jazz fans. It was important for me because I wanted to not only tell Tony’s story, but the drift between Italy and Italians. Tony arrives in Italy in the 1960s just at a time when our country enters into an endless tunnel that will lead it to its current path. Tony’s story reveals the abyss into which this country collapses and the moral degeneration which is now visible to the entire world.”

It’s clear that there’s much more than the mesmerizing music of Tony Scott. “It’s certainly about the figure of the artist who does not bend or compromise, his dedication to his art because he believed that art serves to change the world. On the other hand there is also Dr. Jeckyll and Mr. Hyde, which is a complex personality, a problematic personality with dark sides. So that’s what fascinated me most about Tony, and it also made me think that there were, from time to time, some similarities between our personalities.”

Maresco could not attend the film screening despite very much wanting to do so. “In the first part the film, New York City is the protagonist – the city that gave birth to bebop. I’d like the audience to recognize and feel my own love for this music and for this city that for a thousand reasons I have never had the pleasure to visit.”

Borough of Manhattan Community College

Tribecca Performing Art Center

Theatre 2

199 Chambers Street

New York, NY 10007

Translated by Giulia Prestia

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.