Pirandello's Muse: Marta Abba Unveiled

Friday, at Casa Italiana, Pietro Frassica of Princeton University presented his new book “Her Maestro’s Echo: Pirandello and the Actress who Conquered Broadway in One Evening” (Troubador, 2010), based on the correspondence between the revered dramaturge and his actress- muse Marta Abba. Abba bequeathed her archive to Princeton in the late 1980s and Frassica’s many labors include an English translation of selected letters, published in 1994, and several other volumes in Italian. The new text aims to shed light on the person of the actress, also providing a more in depth analysis of the artistic relationship between the two. A dramatized reading of excerpts by Meghan Duffy and Ric Randig - staged by Mimi Gisolfi D’Aponte and sponsored by the Pirandello Society of America - followed.

The second historic, early 20th century 'artistic' romance Casa Italiana has unearthed this fall, the event complements the Gabriele D’Annunzio exhibit currently on view in the Casa gallery (through Dec. 15). The former pays homage to D'Annunzio's enduring liaison with the diva Eleonora Duse. Moreover, the themes of we encounter here – modernity and language, cinema and technology, representation and perception, art and politics – also find an echo in the Guggenheim retrospective Chaos and Classicism: Art in France, Italy and Germany 1918-1936 (on view in NYC through January 9).

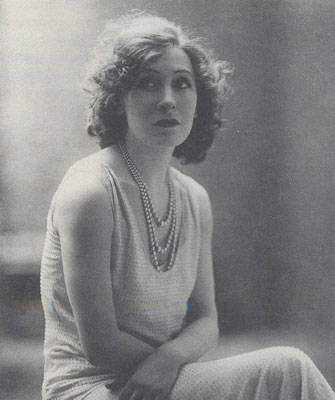

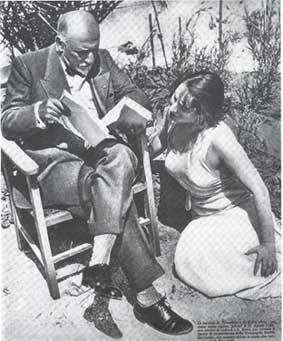

Pirandello and Abba met in Rome in 1925; he was nearly 60, an established and accomplished writer, playwright and director of the Teatro di Roma. She was barely 25, a recent graduate of the Accademia dei Filodrammatici in Milan, flush with enthusiasm after a successful debut in a Milanese production of Chekhov's “The Seagull”. Upon seeing her perform Pirandello wrote to request her collaboration and each, in his own way, would remain forever altered by the encounter. “Come tu mi vuoi”, [As You Desire Me] (1932) is considered to be the best of their joint ventures but their letters do much to illuminate Pirandello’s obscure masterpiece, “I giganti della montagna” [The Mountain Giants], the last of his plays.

Writing Marta from Paris, the poet describes his imaginative toil and the new play elatedly, “The lightness of a cloud over the depth of an abyss; powerful laughter exploding among the tears.” The source and the reason for this rush of inspiration is, of course, Marta herself: “With all your soul, which rejoices in me and creates inside me that sense of a fable in which all the characters breathe, and the words bloom like flowers that seem astonished at being born”(Paris, February 16, 1931).

It is easy enough to dismiss these words as the musings of a man in love with a beautiful young women, but upon reading Marta’s words, we discover that she was no Galatea. A spirited, independent woman with ideas and thoughts of her own, she exhorts her maestro, “I should like it that you extend yourself further […] Do not be afraid to […] embrace everything, including the beauty that fills our spirits with wonder and dismay”(Salsomaggiore, May 28, 1930). In fact, throughout their correspondence, Marta develops from a proud, girlish actress – flirtatious and yet reproachful in response to the poet’s attentions - into a mature and sensitive young woman. From her hotel room in New York in 1936, she reflects upon the plight of the “modern woman” and entreats Pirandello to consider the feminine experience: “with your sharp eye, you might come up with the right words to express it”.

The period in which their correspondence flourished (1925-1936) saw a great deal of transition and turmoil - politically speaking as well as artistically. And, as is often the case, dialogue proves to be all the more revealing – transforming historical personages into nuanced characters on the set of life.

The archive holds some 552 letters penned by Pirandello and 238 in Marta’s hand. Their conversations range from Mussolini to the invention of the ‘Talkie’. They discuss Pirandello’s anxiety over work, money and family and Marta’s concern for female emancipation. This period marked the height of Italian Fascism – and the letters expose the pair’s ambivalence in the face of Fascist politics. Pirandello went abroad (to Berlin) in 1928, presumably to distance himself from the party. Meanwhile Abba was criticized for the “autonomous” nature of her performances and her rather “free interpretation of characters” – neither was appreciated in a young woman. After a visit with the Duce, in her report a “tragic man”, she divulges - not without irony - the statesman’s irritation over Pirandello’s “foul temper”, his homage to Verga, and his dismissal of D’Annunzio.

The portrait of an epoch emerges through this emotionally and intellectually charged exchange: Pirandello, however ready to embrace the new technology - especially in film - struggled with mechanical reproduction and other modern modifications. Swooning over the moon (and Marta) from a balcony in Nettuno at 2AM, he laments her multiplication in the municipal streetlamps. Meanwhile, for her part Abba resisted the film industry, clinging tenaciously to the stage. (Notably, Greta Garbo replaced her in the screen adaptation of "As You Desire Me" (1932).

Perhaps “The Mountain Giants” - in many ways the fictional mirror of Abba and Pirandello's mutual affection - best explains the artists’ struggle with reality. In Frassica’s words, the play is “a testament to the power of fantasy and poetry but also to the tragedy of art in a brutal modern world”. A portrait of the illusive imaginary world Marta helped him to create and maintain, the mild- monstrous ghosts in Pirandello's final poetic effort - living distantly yet nearby in fantastical allegory - also serve to illustrate the contradictory impulses which characterized 'modernity' in Interwar Europe.

Pirandello (b. 1867) expired in 1936 and Abba, who had already moved to the States, married Severance A. Millikin, a wealthy business man and art patron from Cleveland OH, in 1938. Abba’s life spanned much of the 20th century (1900-1988) but, though her performance on Broadway - especially in Gilbert Miller's "Tovarich" - won her praise and fame in the U.S., her artistic career never recovered from her maestro’s loss. She divorced Millikin in 1952 and returned permanently to Italy.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.