Italian Cinema: Where Art and Comedy Coexist

Where does a film buff go when he or she visits Italy?

I think if you really want to do almost anything in film, you have to go to Rome, because that’s where most of the producers are, but Bologna, for example, has the best film archive in Italy. They do wonderful restorations, especially of early Italian silent films, and we once helped the archive with a big restoration project, and we have continued to work with them over the years. But actually one of the recent shifts in Italian film is that it has become quite regional. You now have filmmakers who live and work not only in Milan and Sicily, but in Naples, in Bari, and places you never really thought of as filmmaking centers. But now, of course, with the new equipment people can make films anywhere.

That’s very true. What have been some of the more successful Italian films in the Lincoln Center series?

Of all the Italian shows that I’ve done, I guess the one that I’m most proud of was a very big show on Neo-Realism. Italian Neo-Realism is, for me, one of the watershed moments in film history. It’s really kind of a game changer – not only for Italian but for world cinema. Unfortunately, as happens over time, when people say in the U.S. would talk about Neo-Realism, they were only talking about three or four films, and those were always the ones that we showed.

Can you give us a little 101 on that time period?

We are talking about right after the war, when Italian film studios were largely destroyed or very seriously damaged during the war. Italian filmmakers began taking their cameras out into the streets, shooting with natural light in real locations. Very often the films told stories about common people. In a way they offered a very different kind of cinema than people had been used to. And it had a huge effect all over the world. It was a different way to make films.

Can you name a few exemplary films we might know?

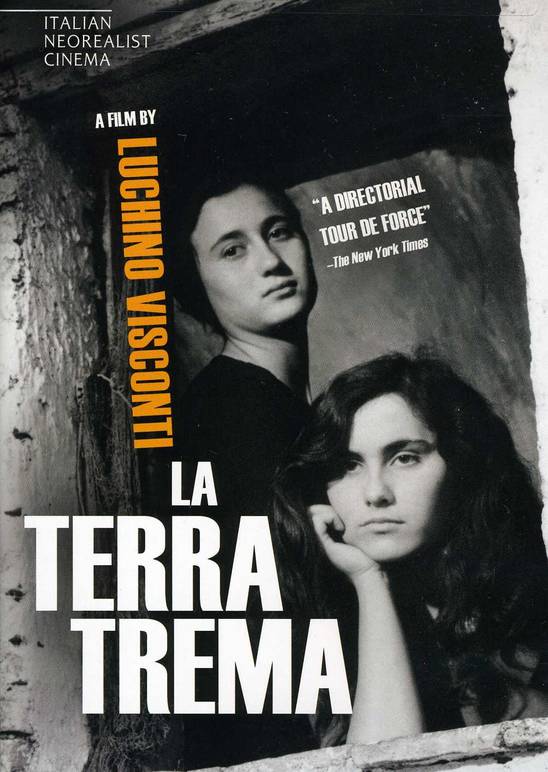

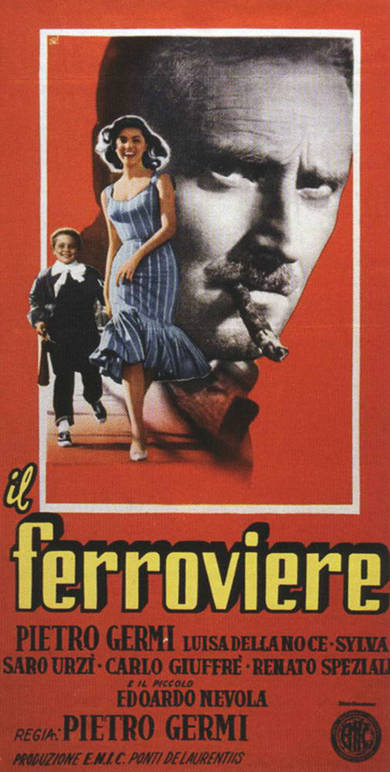

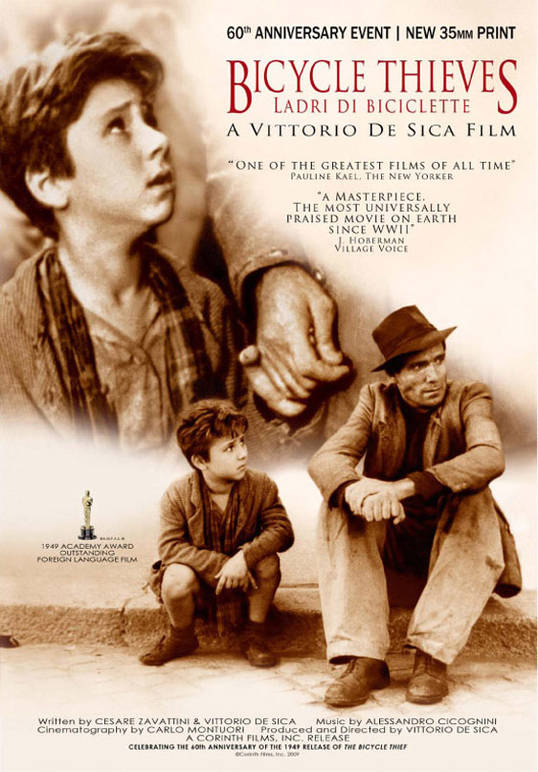

Rome: Open City, The Bicycle Thieves, La Terra Trema. Those are the classics one thinks of when you think of Italian Neo-Realism, the four or five that get shown repeatedly. And they should. They’re great films. But it always bothered me a bit that the movement was actually much broader more interesting than people tend to know. So I decided I wanted to do a very large series on Neo-Realism. After a few years and with the help, of course, of friends in Italy, I was able to put together about 40 films from the period 1945 to 1954. We held a major retrospective of the genre at Lincoln Center in 2009. I was very, very proud of that series because I think it helped shift the discussion and open people up to a whole other group of directors, such as Lattuada, De Santis, Germi, and others who had, in a certain way, been forgotten a bit in this country.

What are a few of these lesser known but worthy films?

Oh gosh, there are so many. The Railroad Man by Pietro Germi, or Lattuada’s The Thief or Senza Pietà – I mean, these are films that give us different shapes and flavors of Neo-Realism. In a way, I wanted to round out that picture [of Neo-Realism] as much as I possibly could. And again I think it had a nice impact; the series was extremely popular. And I’m glad to find in academia people now have a somewhat broader notion of what Neo-Realism was about.

Can you tell us some other periods of Italian filmmaking that you think readers ought to know about?

Again, there’s so much. Italian cinema is just one of the richest of all national cinemas. Certainly the period in the 50s and early 60s was a moment when Italian cinema seemed to be able to do no wrong. On the one hand, Italy had what you might call very serious artistic masterpieces by people like Fellini and Antonioni, and a little bit later by Bellucci or Bellocchio. At the same time, they produced fantastically successful popular cinema, wonderful Italian comedies from that era by Monicelli or Dino Risi. I think one of the strengths of Italian cinema was that both of these segments coexisted.

It is a rich film history. What about contemporary Italian movies?

Well, I was really happy that last year the Oscar went to La Grande Bellezza, which I think is a terrific film by Paolo Sorrentino, but there really is a lot of really good Italian filmmaking going on. I think it’s really not so much the fault of the Italians as it is of our own very limited film culture here in the United States. Very few cinemas show foreign language films and unfortunately the audience for that kind of cinema has dwindled.

Is there a hallmark of Italian film that differentiates it from a Spanish or American film?

I think it’s very difficult to make such distinctions. How do you describe one brand of cinema that contains both Antonioni and Totò? There is an enormous range of sensibilities presented there. So I think it’s hard to really say there is a single essence of Italian film. Again, for me, I would say that one of the hallmarks of Italian cinema has been its ability to keep a balance between popular cinema and a more ambitious kind of filmmaking.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.