Enrico Franceschini. "Voglio l'America" - A Story of Passion and Human Development

ITALIAN VERSION

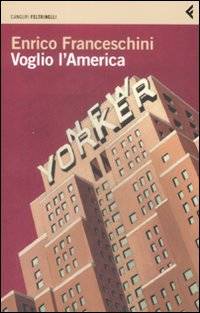

I read Enrico Franceschini’s new book Voglio l’America (Feltrinelli, 2009) in one sitting. It falls into a category that hasn’t yet disappeared despite the current state of affairs: the protagonist as dreamer. Feltrinelli has already published Franceschini’s autobiography Avevo Vent’anni: Storia di un collettivo studentesco (2007) and his novel Fuori Stagione (2006). Franceschini was able to capture the spirit of this category in his new work which takes the form of a novel and interwines two distinct time periods, the 1980s and the present, which are captured and brought to life.

Franceschini was born in 1956 and left Italy at a young age. As a foreign correspondent for La Repubblica in London, he won the Europe Prize for Journalism in 1994 for his coverage of an armed rebellion in Moscow. For his new book he did not rely on the usual autobiographical format to tell the fascinating story of his life as a journalist. Starting out in New York, he recounts his early days in Manhattan in the 1980s, a legendary place for many young people despite its daunting and conflicted reality.

He tells of his lively adventures as he tries to scrape by in an unwelcoming city. He plumbs the depths of journalism without a grasp of the language or any professional connections while trying to make a start in New York City -- Robert De Niro’s Manhattan.

Early on he realizes that life would be much harder than what he gleaned from Hollywood images and the excitement on the basketball court. His passion for the sport was the basis for many of his articles written for local newspapers in Bologna. He tried to make a living by taking on menial jobs while continuing to write and sending unsolicited articles to Italy. (One can only imagine the inherent challenges in doing this before the days of digital media, email, Twitter, etc.)

The progression from his initial articles to his first successful interviews was not a quick ascent, beginning with coverage of American sports leading up to interviews with Steven Spielberg and John Gambino. It was only after a fortuitous connection made through a local newspaper that he arrived at the newly established Italian language newspaper L’Espresso in New York.

Describing his successes and failures until he landed the post as a foreign correspondent from New York, Franceschini always refrains from referring to himself as someone who has “made it.” His book gives us a peak into a mythic time and place with the immediacy and intimacy of an insider’s perspective.

I met Franceschini after his book presentation at the Feltrinelli bookstore in Rome’s Galleria Colonna. I read the first passages as I waited for the presentation to begin, and I immediately decided that it would be worth interviewing him. The presentation opened with remarks by Ezio Mauro, La Repubblica’s editorial director, and Paolo Galimberti, president of the Italian national broadcasting system.

The first thing that struck me was the cover of the book, which shows an image of the New Yorker building, the weekly magazine founded in 1925 by two American reporters. If one believes in omens, it could be said that this choice, instead of, say, the New York Times building, could be seen as a reflection of the publishing world grappling with the global crisis, especially the New York Times. Is there a hidden message behind this choice, considering that the New York Times was considered to be a professional beacon throughout your career?

Book covers are usually a casual choice made by the editor or the graphic designer, as was the case this time. We were looking for a nice image of New York; Feltrinelli liked this one and I did, too. Sometimes casual choices and destiny work well together. The New Yorker building is one of the most quintessential symbols of New York City. I am very fond of that weekly magazine; it’s still one of the best in America. I have been reading it for years every week wherever I am in the world. Many years ago I interviewed the legendary former director William Shawn. The current director David Remnick, a two-time Pulitzer Prize winner, is another great journalist destined to become legendary. The New Yorker is not only a magazine, but more importantly, it implies “resident of New York,” which I also became and I hope to keep my honorary citizenship.

You chose the novel as the format for your work, or I should say, the formation or coming of age novel. It’s a story about professional and personal growth that led you to complete fulfillment as a journalist and as a man. Why did you choose the novel as a genre instead of an autobiography or an essay? By reading the book’s title there seems to be a hint as to what the content might be about.

For two reasons: First of all, the events date back to 30 years ago and I couldn’t realistically remember every single detail, dialogue, or situation and so I had to invent some of them. The novel format relieved me of any guilt I might have felt for inventing the things that came to my mind. On the other hand, when I think about a provincial, 23 year-old boy coming to New York, as I did, with only $1,000, no connections, and a poor grasp of the English language, dying to become a journalist and work in the Big Apple, and that I finally made it, I still can’t believe that it really happened to me. These sorts of things only happen in fairy tales, or in films, or of course, in novels. In this way anyone is free to think, “Oh yeah, it’s a good story but that doesn’t happen in real life.”

At the beginning of the book there is an event, a sort of pre-journey on the train to Brussels. Was that just a literary technique to succinctly convey the significance of the journey to New York, a journey that begins with bad omens that could have deterred you in some way?

The book is autobiographical so there might be some distortions, some inventions that parallel reality. But these only refer to some small details. The substance is absolutely true, as the trip on the train is true. The flight to New York from Milan was too expensive so I took a charter flight from Brussels, where I headed to by train, which was cheaper. I did that using a trick that I won’t reveal here!

The protagonist’s attitude towards various ethnic groups struck me from the beginning, especially since he was politically incorrect and he used racial epithets while, at the same time, not coming across as overtly racist. Reading your book it is clear that you made a cultural journey from a small town to a multi-ethnic society such as New York. Was it automatic for the protagonist or did he have to go through an internal process?

I don’t recall how it was for me, exactly, but I think that it was a gradual process. My story tends to be, or at least I want it to be, an ironic and funny one, sometimes even comical. Political correctness is not laughable at all! When the protagonist dates a Chinese girl so he can have sex with her, he suddenly thinks that she doesn’t have a nose after staring at her for a while. The way in which the whole scene develops and the way he comes to his conclusions is not racist at all. What comes out is that he’s a real chicken shit, not the girl!

Longing for America or longing for Journalism? It was interesting to note how the simple desire to see the United States for the first time was influenced by Hollywood films, and how the mythology of Manhattan was transferred to the rest of the world, and how it transformed itself into a full awareness of the desire to become a journalist. This can be seen in the first few lines: “… my plan was rather simple: conquer America and become a journalist, a writer, and a screenwriter, too…”

Searching for stories to tell, informing one’s country about what is really going on out there in order to free the public’s opinion from stereotypes and prejudices…. Why has American journalism (and Anglo-Saxon journalism in general) always been considered the benchmark for anyone who wants to work as a reporter? What contribution have Italian or European reporters made to journalism?

“Wow it’d take me another book to answer all your questions! Well, let’s just say that the protagonist, or myself as the narrator, doesn’t have these noble goals: he just wants to write, at least at the beginning, he only wants that. He wants to see his name in print, he wants to tell some stories. This is what excites him the most, what drives him. Then it happens that, gradually, he realizes that American journalism is a good training ground, a good education, a place that will force him to become a better journalist. However, this is not very visible in the book; on the contrary it’s hardly perceptible. It’s something to get to, something that will happen in the future. Italian and American journalism are very different. First of all, the latter separates facts from opinions, it clearly understands the difference between good writing and baroque style, and it works really hard to find out the facts and verify them. Of course, Italy also has many excellent journalists; however there is a big difference between a small, local American newspaper and an Italian one, where the former clearly outstrips the latter… And even though there are many Italian reporters who have gained their experience in America and have contributed a great deal to Italian journalism, American journalism still has an advantage.

The periods that frame the novel highlight the passage of time after the first year in New York.

Thirty years have passed, full of experiences and emotions that have created a story of passion for a profession and writing itself. Is this still possible nowadays? Looking at the current global crisis, especially in journalism and the editorial field, and the new ways of providing people with information (such as the Internet, digital television, blogs, Twitter, etc.), does printed paper still have a value of its own?

Well, answering these questions will also take another book or two! If I were 23 years old today with the same hopes and dream, I’d choose Shanghai over 21st century New York. I would try to learn Chinese first and then start sending my articles from there. Of course, it would be more complicated but I’m sure anything is possible. As far as the value of printed paper, what really matters today is information: information, news on paper or in a digital format – an instrument to transfer the information will always be necessary. Stories from your own city, nation, or around the world will always need to be shared. I agree with Thomas Jefferson’s point of view: “Should I choose between a government without information or information without a government, I wouldn’t hesitate and would pick the second solution”.

The same opinion was shared by Mr. Barack Obama, President of the United States during a press conference. Notwithstanding the present situation and the current state of affairs, sometimes it is worth believing in omens and signs.

(Edited by Giulia Prestia)

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.