Italian American Identity: To Be or Not To Be

In the 1950s and early 1960s, it was the accepted view among many social scientists that, as ethnic assimilation advanced, ethnic group identities would fade away. But in fact, ethnicity continued to impact significantly upon political life. Why was that?

Acculturation and Assimilation

In 1967, I published an article in the American Political Science Review arguing that assimilation would not wipe out ethnic politics and ethnic identities in the foreseeable future because assimilation was not happening.

I suggested that we needed to distinguish between culture and social systems. A culture is a system of beliefs, values, images, lifestyles, and customary practices including language, law, arts, and the like. A social system consists of the structured relations and associations among individuals and groups both formal and informal: family, church, school, workplace, and other networks of roles and status. The culture is mediated through the social system or social structure, as it is sometimes called.

To become well practiced to a prevailing culture is to acculturate. To become absorbed into the dominant social structure is to assimilate. Since the beginning of the American nation the Anglo Protestant nativist population has wanted minority ethnic groups to acculturate but not necessarily assimilate. The "late-migration" Southern and Eastern Europeans were expected to discard their alien customs and appearances offensive to American sensibilities. A new verb was invented: they had to "Americanize."

To make matters worse, these immigrants of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries settled mostly in the large urban centers of the Northeast and Midwest (where the jobs were), places that small town Protestant America already loathed as squalid and decadent hellholes.

The public schools became special agencies of acculturation to be imposed on the immigrant children. As a child in a classroom full of Italian-American grade-schoolers in New York City, I was treated to patriotic tales about George Washington, Nathan Hale, Paul Revere, and other of our "heroic founders." We recited the Pledge of Allegiance and sang the "Star-Spangled Banner" and "America the Beautiful." And I recall at least one of my teachers telling us in an annoyed tone: "Tell your parents to speak English at home."

By the second-generation (children of the immigrants), the ethnics already had undergone a substantial degree of acculturation in language, dress, recreation, entertainment tastes, and other lifestyle practices and customs, while interest in old world culture became minimal if not nonexistent.

However, such acculturation was most often not followed by social assimilation. The group became Americanized in much of its cultural practices, but this says little about its social relations with the host society. In the face of widespread acculturation, ethnic minorities still maintained social group relations composed mostly of fellow ethnics.

The pressure to acculturate was not accompanied by any invitation to assimilate into Anglo Protestant primary group relations within the dominant social structure. It seems the nativist bigots well understood the distinction between acculturation and assimilation, even if they never actually used such terms. In a word, "You must Americanize but not in my social circle."

Dual Identities and Group "Traumas"

Many of the crucial images that a marginalized ethnic group has of itself do not come from itself but from the dominant culture and dominant social order. For us Italians, the immigrant generation was reduced to a Luigi caricature, a simple soul who spoke in a pasta-ladened accent. Then came the perennial Mafia mobster, recently given new life with The Sopranos. Also still going strong are the television commercials portraying large boisterous Italian families gathered around the dinner table to shovel immense amounts of food into their mouths and at each other in what resembles an athletic contest.

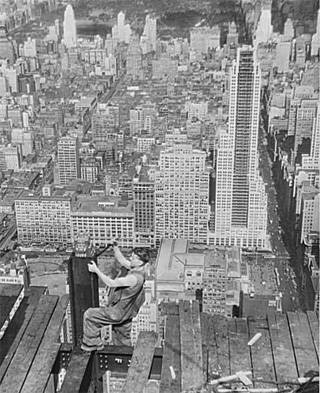

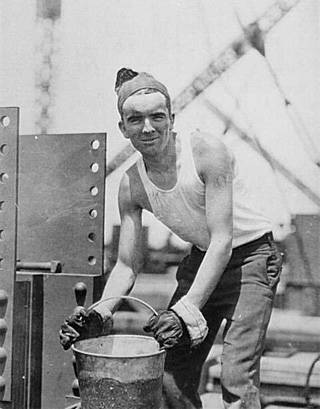

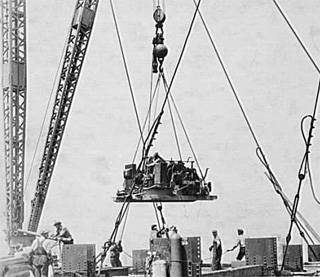

Another enduring stereotype is of the Italian American as a working-class boor, a dimwit proletarian, visceral, violent, and thoroughly unschooled. There is nothing wrong with being working-class but there is plenty wrong with a vulgar class caricature that defames all working people (whatever their ethnic antecedents). Left out of such scripts are the realities and struggles of workers, a subject seldom treated in the mainstream news or entertainment media.

Media stereotypes aside, there exists a duality in the Italian-American self-identity: on the one hand, a strong in-group pride regarding our heritage and an assertion of our worth as Italians to counteract the wretched stereotypes, along with strong family involvements that remain ethnically tinged, to say the least.

On the other hand, there are the strenuous assertions of our "100 percent Americanism" as a way of overcoming social marginalization. This is what I have called cultural ambidexterity, the promotion of both ethnic pride and Americanism all at the same time, usually accompanied by a political conservatism.

It is an image duality that fits into the acculturation/assimilation model: we acculturate to the American identity, often with a compensatory militancy because of our being somewhat marginalized and unassimilated. This marginalization at the same time adds to our determination to hold to an Italian group awareness and loyalty.

There are ethnic groups that have sustained enormous historic trauma, leaving them with an enduring mega-narrative. For them, ethnic identity is an especially strong imperative. A few prominent examples:

African Americans who have braved centuries of slavery, plus a century of segregation and lynch-mob rule, and today the persistent poisonous sting of White racism.

Jewish Americans who have been victimized by two thousand years of Christianist inspired anti-Semitism and violence capped by the historic trauma of the Holocaust.

Latino-Americans and Asian Americans who would be much further along the assimilation track having been fairly early arrivals, but whose ranks have been lately infused with millions of newcomers, thereby raising fresh issues of acculturation, economic hardship, and even residential legality, all of which heightens a defensive awareness of group identity. In the case of Asian-Americans--and to some extent with Latinos also--there is the additional mark of racism with which to contend.

Arab Americans and Persian Americans in this country in relatively smaller numbers with less visibility but who in recent years have been unjustly harassed and stigmatized as being associated with terrorist groups.

In each of the above examples, group identity retains a special saliency because it is linked to past or present issues of discrimination and mistreatment. What I wrote in my 1967 article still seems to hold: while much ethnic militancy and group boosterism is considered clannish, it "is really defensive. The greater the animosity, exclusion, and disadvantage, generally the more will ethnic self-awareness permeate the individual's feelings and evaluations."

In addition, let it not be forgotten that people retain ethnic attachments not only because their group is under assault but because the attachment provides a nurturing social and cultural experience. So along with the negative-defensive identity we have the positive-enjoyment ethnic experience. This is as true of Italian-Americans as of any group in the United States.

The Future Has Arrived

Does assimilation happen to any ethnic group? Yes indeed. Those northern European Protestants who invaded this country in what are called the "early migrations" of the seventeenth, eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, riddled as they were with sectarian enmities and national differences, pretty much blended into the nativist melting pot by the mid-19th century. Today persons of long settled and much mixed northern European Protestant lineage are often notably vague about their antecedents. Their ethnic identity is a matter of no great urgency and has a low saliency to their self identity.

Some white Protestant immigrants are relatively recent arrivals yet they have enjoyed a fast-track assimilation, given their linguistic, physical, religious, and tempermental resemblance to the Anglo-American Protestant prototype. British workers who migrated here at about the same time as Italians, Greeks, and Jews were more or less well assimilated within one generation.

The 1967 article I wrote about ethnic assimilation--or rather the absence of assimilation--focused on the Southern and Eastern European groups of the "late migrations" of 1870-1914. I concluded that ethnic identity would persist and would continue to play a role in political life well into the distant future. My article relied on data from the early 1960s but also from the 1940s and 1950s, in other words, as much as sixty or seventy years ago.

With this passage of time, one might say that the "distant future" has arrived, at least for the white ethnics: the Irish, Poles, Italians, Greeks, Portuguese, and others. Today the ethnic identities of these late migration groups have much less saliency. This can be seen most dramatically in the political realm where references to a candidate's ethnicity have become quite rare unless the individual is African-American, Latino, or Asian.

Recall how John F. Kennedy's Irish Catholic antecedents were such a touchy issue in the 1963 presidential contest. But by 2004 it no longer mattered that Democratic presidential candidate John Kerry was a Roman Catholic. And in the 2008 election, it went largely unmentioned that vice presidential candidate Joe Biden was Irish Catholic.

In 2006 the media took no notice that Nancy Pelosi was the first Italian-American Speaker of the House; instead attention dwelt almost exclusively on the fact that she was the first woman to occupy that post.

For years Italian-American organizations had called for an Italian-American appointment to the Supreme Court. By 2006 there were two Italian-Americans on the Supreme Court, Antonin Scalia and Samuel Alito, both conservatives. Progressive Italian Americans like myself were not dancing in the streets bursting with pride. If anything, we opposed both nominations. Obviously the politics of such jurists were of more significance to us than their ethnic antecedents.

In fact, as far as I could observe, no one took note that there were two Italians on the High Court except for the several conservative Italian-American organizations that ran full-page ads in 2006 designed to misrepresent those who opposed Alito on political grounds as being opposed to him out of ethnic bias. Thus the ads argued that Alito was being derisively called "Scalito" (true) because of some anti-Italian prejudice (untrue). Actually the conflation of names was invited by their similarity and impelled by the fact that Alito was a right-wing reactionary twin of Scalia's.

Pre-election opinion polls and exit polls published in the mainstream press reveal what groups are still in the public consciousness and what groups have faded into the background. After the 2008 presidential election, the New York Times devoted an entire page to how various groups in America voted. The Times broke down the electorate by income, gender, education level, region, and religion, but no ethnic groups other than Latinos and African-Americans.

Gone were the old time Harris-poll and Gallup-poll reports on how Italians, Irish, Poles, Germans, Hungarians, Portuguese, Greeks, and the like have voted. The white ethnics of the late migrations seem to have assimilated into the electoral mainstream, at least as distinct voting groups.

Good-bye Columbus

Those of us who are Italian-Americans might ask, is assimilation our ultimate fate? And does assimilation mean disappearance as a distinct ethnic entity? Is it our destiny to be melted down by the melting pot, going the way of the earlier Anglo-Protestant groups?

Be aware that social assimilation also leads to a high degree of biological assimilation, in other words, intermarriage and interbreeding with increasing numbers of offspring who are of mixed heritage. This growing tendency toward intermarriage has been a source of concern among some Jewish organizations that posit the question: "Will intermarriage succeed in doing what 2000 years of oppression could not do?" (namely bring about the disappearance of the Jewish people).

For Italian Americans at the present time ethnic awareness still retains a significant saliency even among those who attain high levels of education and professional training--as demonstrated by the rich offering of scholarly papers presented at the yearly meetings of the American Italian Historical Association.

There is no reason to assume that a person's identity choices are mutually exclusive rather than multifaceted. Multiculturalism can obtain not only in society but within individuals. And individuals of mixed descent can enjoy multiple identities and loyalties.

In addition, as noted earlier, ethnic identity is not only reactive but proactive, not only a defense against derogatory stereotypes, not only a compensatory assurance of group worth, but a positive enjoyment, a celebration of our history and culture in this country and in Italy. It is a way of connecting with others in what too often is a friendless and ruthless market society, a nurturing identity that is larger than the self yet smaller than the nation.

It would do well if we could bring more of a social content to our ethnic identity. The Italian-American Political Solidarity Club has just published a book whose title urges as much: Avanti Popolo: Italian-American Writers Sail Beyond Columbus. The book urges that on Columbus Day instead of celebrating conquest we should acknowledge those who fought for the rights of all immigrants and for social justice.

Indeed Italian Americans need to bring substance to the symbolic politics that have been fed to us. We do not need another statue to Columbus. Some such as Diane Di Prima, Tommi Avicolli-Mecca, and Juliet Ucelli have organized "Dumping Columbus" readings and other events that challenge the iconic image of the Great Navigator and instead commemorate the Native Americans he enslaved and murdered.

Philip Cannistraro and Gerald Meyer (of German Protestant lineage) edited a book, The Lost World of Italian-American Radicalism, that reclaims some of the history of radical Italian-American immigrants, labor leaders, union organizers, antiwar activists, and political protesters, a history long neglected or repressed.

To frame the Italian-American experience within a context of struggle for social justice and economic survival is to give it a dimension that goes beyond nostalgia and sentimentality, and flies in the face of the stereotypes that weigh down upon us Italians. Thus do we not only realize more of ourselves but we connect to more of the world, especially to the class realities that compose so much of life yet remain too often unmentioned and unnoticed.

* Michael Parenti (www.michaelparenti.org) is the author of twenty-one books including The Assassination of Julius Caesar (New Press), The Culture Struggle (Seven Stories), Contrary Notions (City Lights), and God and His Demons (Prometheus Books, forthcoming).Reprinted by permission of the author.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.