The Italian American Community’s War on Negative Stereotypes: a Failure

Some random thoughts:

In charging Italians and Italian Americans with confronting the “unbearable prejudice” of association with organized crime, Saviano has actually reminded us of our collective responsibilities. Like Paul Ginsborg, Maurizio Viroli, Alexander Stille and others who, in examining the phenomenon of “Berlusconismo” have charged Italians with the responsibility of such a deplorable political development, Saviano grants agency to Italians and Italian Americans. We are not just the passive victims of the reality and the representations of Mafia and Camorra, but are (or should be) the writers of our own history.

At a recent conference on Naples at Hofstra University, I was stunned and outraged when several people in the audience (not academics or scholars) criticized us for having organized a panel on the neo-melodica musical tradition in Naples and its relationship with the Camorra. How dare we criticize Naples and defame the Neapolitans? I asked: “Are we supposed to only talk about pizza and ‘O sole mio’”?

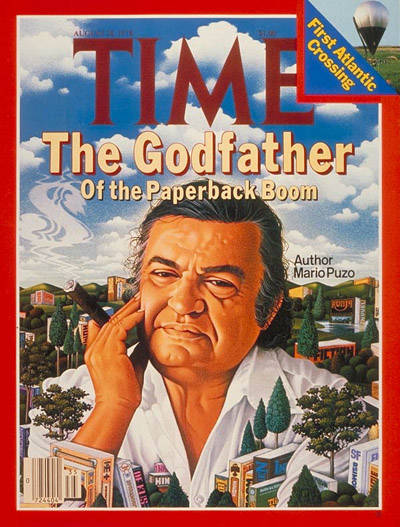

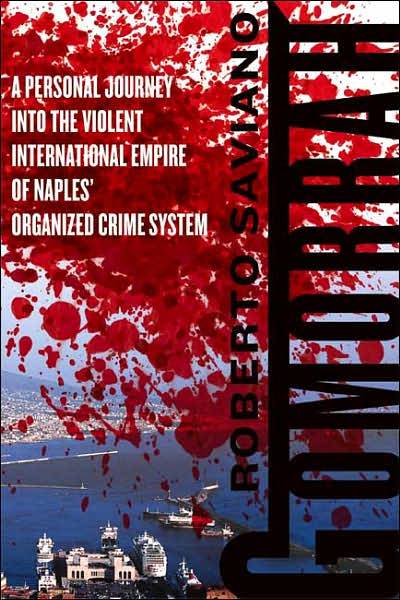

As much as I admire Tom Verso’s writing, I think he overstates his criticism of Saviano. One of the more interesting aspects of Saviano’s journalism and his talk at NYU is the insistence on the inter-connected relationship between capitalism and organized crime; between crisis capitalism and criminal capitalism, or, what I have called in my course on Naples last semester as students and I were discussing Saviano’s book, “capitalism on crack cocaine.” Included here is Saviano’s explicit condemnation of the “legitimate” economy. What does it mean when Citibank openly launders $200 from Raul Salinas (brother of former Mexico president Carlos Salinas) who had an “official” salary of $190,000? To paraphrase Mario Puzo: “you can steal more money with the point of a pen [or the click of a mouse] than with the point of a gun.” How are we to interpret that just three weeks after the fall of Berlusconi, Michele Zagaria, infamous Camorra boss, is arrested in Naples after being sought by the police for nearly two decades?

There is currently in vogue a tendency to criticize Saviano as a lightweight, a media-hound, a celebrity in love with his persona. I was in Pescara in July 2010 when he received the Premio Flaiano and moved when he thanked the people and police of that city for putting him up at a seaside hotel where he could hear the ocean at night instead of the usual police barracks he was used to. The death threats against him are real and he should be credited with showing us a more sophisticated understanding of organized crime.

Also, note how Saviano speaks about the reporting of organized crime: it is much easier to speak about the depravities of bosses, of their ostentatious villas and Hollywood-inspired dress, clothing and mannerisms, of rendering the AK-47 into a fetish object. (Gomorra – both book and film – are guilty of this to some degree.) It is much more difficult, as Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino did, as Saviano does, to understand the incredibly complex web of legality and illegality, commerce and cocaine, consumerism and violence, banking and bullets. This is what truly renders him a dangerous man in the eyes of others.

I would suggest that, like the “war on poverty”, the “war on drugs” and the “war on terrorism,” the Italian American community’s war on negative stereotypes to date has been a failure. Protesting negative media representations is all well and good, but what we are lacking is a sense of the ironic and tragic nature of history.

“Italy is a country that’s forgotten how its emigrants were treated in the United States, how the discrimination they suffered was precisely what allowed the Mafia to take root there.” Saviano wrote in an op-ed essay for the New York Times on January 24, 2010, commenting on how recent African immigrants to Calabria were struggling against the ‘Ndrangheta. “It was extremely difficult for many Italian immigrants, who did not feel protected or represented by anyone else, to avoid the clutches of the mob. It’s enough to remember Joe Petrosino, the Italian-born New York City police officer who was murdered in 1909 for taking on the Mafia, to recognize the price honest Italians paid.”

I recently learned that Saviano’s mother is from the tiny Jewish community in Naples. So perhaps it is fitting that we recall the saying of the founder of Hasidism, the Baal Shem Tov, “Forgetfulness leads to exile while remembrance is the secret to redemption.”

Stanislao Pugliese is professor of history and the Queensboro Unico Distinguished Professor of Italian and Italian American Studies at Hofstra University. He is the author, most recently, of “Bitter Spring: A Life of Ignazio Silone.”

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.