Sergio Rubini Discusses His New Film: Il Grande Spirito

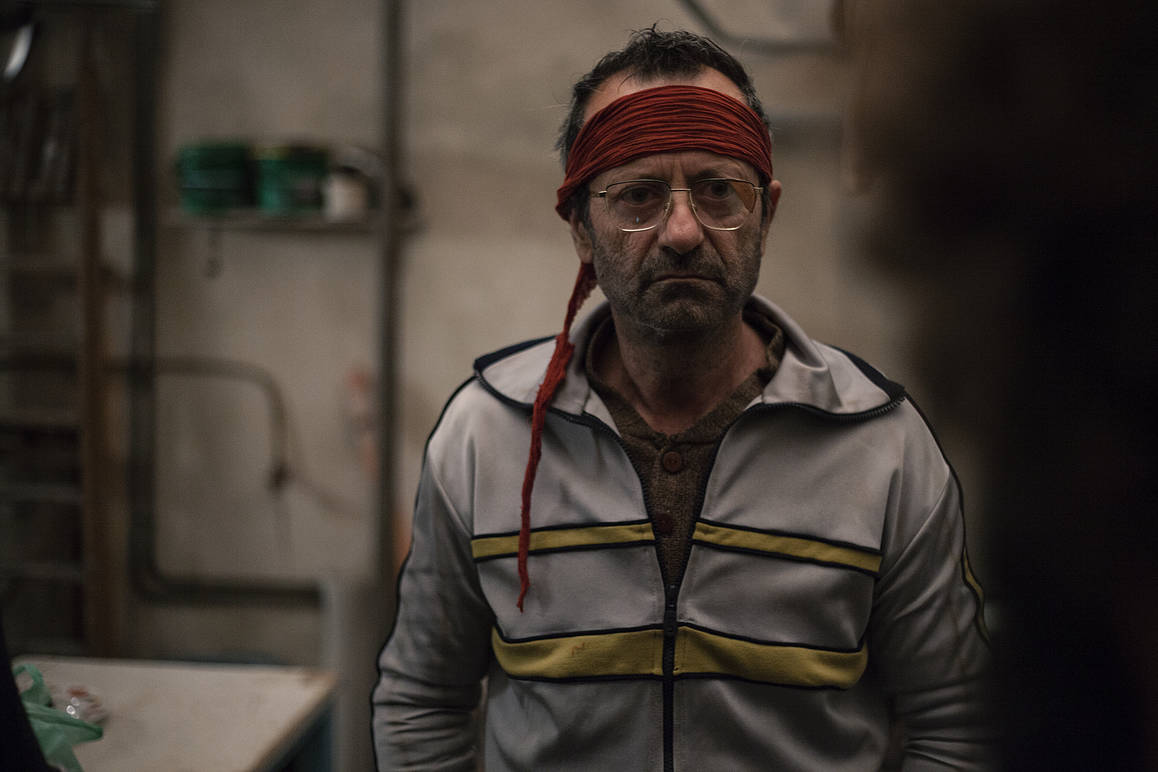

During a robbery on the outskirts of Taranto, one of three accomplices, Tonino (Sergio Rubini) a.k.a. “Barboncino” (poodle), takes advantage of his colleagues’ distraction and runs away with all the goods. His escapes upward, going from roof to roof, until he reaches the highest rooftop and takes refuge in an old water tank, where he finds Renato (Rocco Papaleo), a strange and eccentric individual who claims his name is Cervo Nero (black stag) and he belongs to a Sioux tribe.

Tonino, who is forced to remain there, realizes his only alternative is to team up with this peculiar character who acts “like a Native American” and who, perhaps because he sees the world from another perspective, might be able to give him the key to solving the absurd situation he finds himself in and even change his entire existence.

“Il Grande Spirito” (the Great Spirit) is a new film by Sergio Rubini, which was presented at Bif&st, the Bari International Film Festival 2019. Produced by Fandango and Rai Cinema, it opened in Italian theatres on May 9th through 01 Distribution.

Sergio Rubini, goes back to directing and for the occasion he crafts an incredible character for Rocco Papaleo, who reveals to be perfect in such a different and unexpected role. In a suspended place, framed by the roofs and chimneys of the Ilva steel plant in the distance, the lives of two men meet as they form a strange, crazy friendship: Tonino and Renato are each other’s “Man of Destiny” because by confronting each other they spark their inner light. A film dense with metaphors, where the fate of the Native Americans who were brought down by the advent of railroads, seems to be adapted to a modern context, that of Taranto, where people are confronted with ‘steel monsters’ and where spirituality and ascent (both physical and spiritual) serve bring catharsis.

For the occasion, we met with director Sergio Rubini.

What is this film to you?

It’s a comedy with a bitter undertone because it’s set in Taranto, which has been poisoned by steel monsters, just as it happened to the Sioux with railroads. The character of Renato, masterfully interpreted by Rocco Papaleo, in fact believes he belongs to a Native American tribe who faced the challenges of those times. It’s also a story of friendship that tells us how friendship can, in a way, save us. It’s a story of salvation, an optimistic film with a positive message, against cynicism because I believe that a film should always give a message. People should walk out of the movie asking themselves what it is that this man (points to himself, e.d.) wanted to transmit.

Taranto emerges as the backdrop of this film. So, even though the city is very present, you still managed to make this a ‘universal’ film, set in a sort suspended universe, possible anywhere.

Absolutely. I’m happy that the idea that this movie could take place beyond a specific territory comes across. It’s also true, however, that the history of Taranto is unique and can’t be easily found elsewhere; I want to remind everyone that Taranto is one of Italy’s most beautiful cities, it’s a city with two seas. Unfortunately, however, like the land of Native Americans, Taranto has been devastated by steel; many people died - let’s also remember that the percentage of work-related deaths is extremely high - and many are forced to work with the Yankees, the bearers of evil, that is with Ilva. This profound contradiction characterizes this city, so I could have changed the entire movie but I couldn’t leave out Taranto.

Where did the idea for this film come from?

When I was a young boy I liked the “Indians.” My father had described them to me for what they were. In movies at the time they were different, dangerous, the bad guys. My father gave me another version, explaining that they were victims, that they were, yes, different but good: they had a fantastic worldview, their spirituality was incredible, they lived together with nature and believed that God was everywhere. So the desire to tell the story of the last Sioux merged with Taranto and then I constructed the characters. I wanted to tell the story of these “last” people, so different from each other that it would even be comical, make people laugh. By the way, I was almost sad to have Rocco play Renato (smiles, e.d.) because I wanted to play him myself. After meeting Rocco though and seeing his enthusiasm, I understood that he would have done him wonderfully; and comedians are able to interpret complex characters showcasing all of their humanity.

Renato’s spirituality is a device for escaping the Yankees then?

Renato isn’t dissimilar from the bullied retiree from Manduria. At one point, Rocco’s character climbs up roofs and some kids make fun of him, pull down his pants. It always starts like this, with games, and then the cynicism that surrounds us, which we learn from the media and feels inevitable in life, brings us to commit monstrosities. I believe that these “crazy” people are bearers of wisdom, that they are the most reasonable. Renato’s idea in the film is the most reasonable: cynicism only helps us to get through the moment and live in the present but it gives us no prospects for the future.

One of the prizes of this festival is dedicated to Fellini. You had the honor of working with the maestro, what can you tell us about him?

I had the chance of having this encounter, just how in my movie when Cervo meets the Man of Destiny and it changes Tonino’s life. I was 22 years-old and I met the Man of Destiny, Fellini, a person who has remained with me throughout my life. A master, an angel of sorts, for me it’s a very intimate and private thing, something I carry inside, moving, indescribable and unexplainable.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.