The Secret Behind the Pseudonym

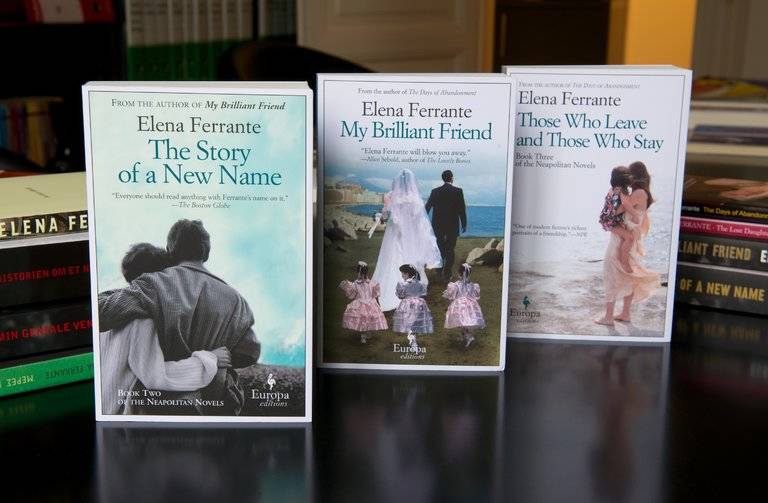

From the beginning of her extensive writing career in Italy, the internationally recognized author of the four part, Naples based, book saga that includes My Brilliant Friend, The Story of a New Name, Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay, and The Story of the Lost Child chose to write under the pseudonym Elena Ferrante since the early ‘90s.

On October 3, 2016 at 1 am an Italian investigative journalist Claudio Gatti (whose name translates to Claudio the cat) released an article to the New York Review of Books stating he had acquired adequate information to prove that Anita Raja, German translator for the Rome based publisher Edizioni E/O and wife of Domenico Starnone, is Elena Ferrante.

Even though Gatti has Italy buzzing about the news, Ferrante’s fan base is not receiving the released information so courteously in the article he entitled “Elena Ferrante: An Answer?” Before delving into Claudio Gatti’s intrusive accusations, we ought to understand the author’s reasons for protecting her identity.

Originally claiming that she chose to write under a pseudonym because of her shyness, Elena Ferrante quickly became a name for sexual liberty and a mother figure for the feminist movement in Italy and around the world. Committed to the choice, the author further explains that she does not stand for competitive writing between authors. She is persistent in her belief that putting a face to a book is unnecessary, and that the book’s power hails from the written word, not the face that promotes it.

Despite consciously rejecting facial recognition, avoiding public promotions, and entrusting her writing to do all the heavy work, Ferrante was betrayed. Claudio Gatti has sleuthed his way into real-estate records, payments from publishers, and literary interpretations. All of these may seem far-fetched, but they are enough for him to connect the translator to the alias.

Through his article he has “outed” an artist who had made a specific and personal career choice for none other than to place her writing and audience on an anonymous level. Gatti has gone beyond speculations to seek tangible evidence to connect Ms. Raja and Ms. Ferrante.

So how, exactly, does Gatti’s article convince English, German, French, and Italian readers (the languages in which he has his article released) that his findings are legitimate? Especially when the audience does not want to know the truth.

He began with payment records he acquired from Edizioni E/O, the company that publishes both Ferrante and Starnone’s work. In his article, Gatti states that there is a connection with the publishing house’s annual revenue, the number of Ferrante’s books sold, and the income of the husband and wife. Through an anonymous source he obtained information that led him to believe that between the financial patterns of the company and Raja’s income checks, Ferrante and Raja are the same.

He then goes so far as tracing the couple’s real estate expenditures from the early 2000’s to present day. Since Anita Raja is a translator, and her husband is a writer, Gatti claims that the two could not possibly afford their 2,500 square foot apartment in Rome and their Tuscan mansion.

Next, he made reference to previous conspiracy theories that attempted to identify Ferrante. The first one being that Ferrante is actually Domenico Starnone, Raja’s husband. Gatti’s article states that based on evidence obtained from a Sapienza University of Rome student-based side-by-side text analysis, there must have been some sort of “unofficial collaboration” between the husband and wife. This means that his belief, as presented in his article, is that the work of Ferrante is Raja’s with influences from her husband’s writing style.

The theories do not stop here. When Claudio begins to claw through Ferrante’s literature and penname, he claims that the name Elena was chosen after Raja’s aunt. Highly studied literary scholars have already proved that her name is a play on Elsa Morante, an Italian novelist and huge inspiration to the work of Ferrante and feminist literature. Many connections are made to Morante’s life and Ferrante’s new novel Frantumaglia, which is written in autobiographical form; a novel Ferrante has countlessly claimed that it is a work of fiction. Even though Cladio attempts to make incorrect relations between the book’s plot and Raja’s upbringing.

Another interesting connection between Raja and Ferrante is her work with Christa Wolf. Raja translated Wolf’s rendition of the classical tale Medea into German, later Ferrante published "The Days of Abandonment," a modern take on the similar Ancient Greek tragic themes. For Gatti this is enough to prove Ferrante’s connection with Raja, but the themes of the Greek and Roman Classics such as Medea, and many others from mythology/theater have been revamped and recycled for generations.

Gatti finally attempts to make in-text connections between Raja and Ferrante. First being the name Nino, romantic subject of the main character of her four part Neapolitan saga released from 2012-2015, is also the family name of Raja’s husband. He also highlights a significant amount of detail about the importance of libraries, a hot topic in My Brilliant Friend. He claims this is Raja’s personal input being that she has been the head of Rome’s European Library. These are truly just two small details in twenty years of Ferrante’s writing that Gatti clings onto.

In all honesty, his strongest case lies heavily in the financial and real estate records. In an attempt to extract more personal information from Raja, her husband, and those working at Edizioni E/O, Mr. Gatti had countless unrequited phone calls and stark conversations that left him without information as he pried for more tangible evidence. Everyone’s refusal to comment on the previous indignations and his overall lack of concern for privacy and protection of Ferrante’s identity has left Gatti sneaking around for his own answers.

But there is one thing Ferrante has that Gatti will always lack, a loyal fan base. Copies of her work have been sold to forty different countries, and when it comes down to it, Gatti is the only one trying to out her, but disrespect can only get him so far. Ferrante clearly does not want to give up her anonymousness for upstanding reasons that she has been open about. For this reason she prefers to conduct her interviews via email and does not partake in book tours.

So wherever the true Elena Ferrante is, weather she is Anita Raja or someone else, I hope she reads Gatti’s article with a smile, confident in the support base of her present and future readers, and aware that the work she has done is far superior to the work of a sleuth.

I wish I could write as mysterious as a cat. -Edgar Allan Poe

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.