In Search of the Real Caravaggio

ROME – Archivists toiling away in dusty libraries are the Cinderellas of art history, and yet the men and women whose building blocks of documentation recreate the greatest glories of culture. So it is with Caravaggio. Marking the fourth centennial of his death, he is the subject of an elegant exhibition of original archival material supplemented by paintings—two Caravaggio masterpieces and others by his peers. Caravaggio in Rome, Una Vita dal Vero (Caravaggio in Rome, A Life Seen from Truth) is on view through May 15 inside the original La Sapienza University of Rome building with its chapel by Borromini, Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza. This was Caravaggio territory: here he lived, worked, drank in taverns, and walked the streets with his friends in the middle of the night. Here too he quarreled—just why and how often is being revealed only now, in the work of a team of seven young art historians, paleographers, archivists and historians from the Tor Vergata University in Rome.

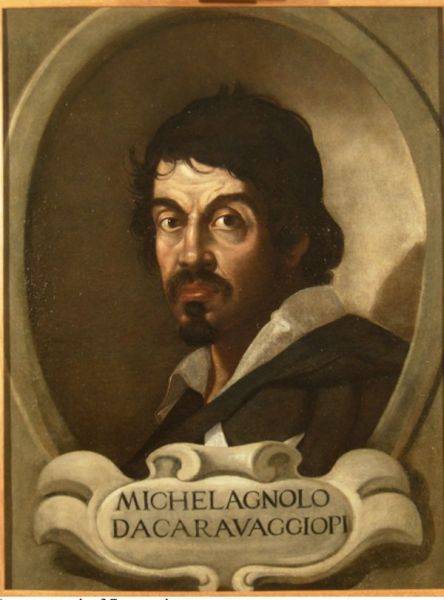

Michelagnolo Merisi (his real name) da Caravaggio was born in 1573 and died in 1610, aged 37. He was an extraordinarily visionary artist who marked the point in time when the Renaissance gave way to the Baroque. For his experiments in creating chiaroscuro effects he is considered the first modern painter. He was also among the earliest to depict ordinary people in extraordinary situations, as in his inspired chapel wall paintings of around 1600 known as the Calling of St. Mathew in the Church of San Luigi dei Francesi in Rome.

Any Caravaggio exhibition is a blockbuster, and art historians acknowledge that he ranks in popularity today with Michelangelo, Raphael and Leonardo da Vinci. Besides his visionary works of art, his turbulent life style captures imaginations, and book shelves are well stocked with biographies. However, knowledge of his life has been based largely upon diplomats’ reports sent to such foreign states as Mantua and Lombardy. An important early account of his life was written by Giovanni Pietro Bellori, but Bellori was born three years after Caravaggio died. Caravaggio himself left no diary, no last will and testament, either because he was illiterate or simply died too young.

Inside the old university building, the team was confronted with more than 60 kilometers of material inherited from the Vatican by the Italian state after unification in 1870. These official records, assembled into thick, ribbon-tied volumes called faldoni, were believed to include complaints to Vatican gendarmes (the birri, they were called) about Caravaggio and summaries of testimony given by witnesses at Inquisition tribunals. But the documents were in too poor condition to be deciphered properly until every page of his Roman years was restored. And there was urgency. The high acid content of the iron gall ink was eating up the documents; without restoration, all would be lost. To finance the slow restoration of ten volumes, each with from 600 to 2,500 parchment pages, art historian Eugenio Lo Sardo, director of the state archives, appealed to sponsors. From all walks of life they responded, among them the Italian Tobacconists Federation, the Axa Insurance Co. at Frosinone, Autoservizi, a bus company, and one individual, Prof. Giovanni Pezzola.

The results have shown that Caravaggio was not born in the Lombard town of that name, but in Milan, and that he came to live in Rome not at age 19, as had been written, but when he was 25, making him something less than the child prodigy heretofore depicted. The new information also sheds light on his friendship with a kindly Sicilian artist, his wife and four children. The police blotters and court records also document just how aggressive he was. In one instance, around 2 am on May 4, 1598, Caravaggio was stopped by a policeman, Lieut. Bartolomeno, near Piazza Navona carrying a sword. Asked he he had the requisite permit, Caravaggio retorted that he had verbal permission from his patron, Cardinal Francesco Maria Del Monte. Indifferent to the name-dropping, the lieutenant hauled Caravaggio off to the Tor di Nona prison.

Two years later one Girolamo Spampani of Montepulciano was purchasing candles in a Via della Scrofa shop at 3 am on Nov. 19, when he was attacked. Spampani told police that Caravaggio beat him with a stick and tore his cape with a sword. The artist ran away, but was recognized. Again, on the night of October 1, 1601, Caravaggio was in the company of friends on a road near Piazza Campo Marzio when he ran into Tommaso Salini, whom he insulted and then assaulted. “With the sword he was carrying he hit me from behind and wounded my arm, which I had raised in my defense,” Salini testified. Caravaggi allegedly insulted Salini as well, saying, “becco fottuto,” or “[shut your] fucking beak”. (Although this incident was partly described in l994, the new documentation is the first complete account.)

On April 24, 1604, Pietro da Fosaccia, a young waiter in the Osteria del Moro tavern complained to police that after serving Caravaggio eight artichokes, he was assaulted. When the artist asked which were cooked in butter and which in oil, Fosaccia suggested that Caravaggio should sniff the artichokes to find out for himself. An infuriated Caravaggio grabbed an earthenware platter and flung in into Fosaccia’s face, injuring the boy’s left cheek. Witness Pietro Antonio de Madiis verified the account.

Six months later, on October 19, 1604, Caravaggio dined at the Torretta tavern with a book dealer named Ottaviano Gabrielli and errand boy Pietro Paolo Martinelli. Later, near Via del Babuino, they began insulting policemen making night rounds and throwing stones at them. Questioned, Caravaggio claimed that he’d been walking and chatting and had heard the stones being thrown, but had no idea who had thrown them. He was arrested..

On May 28, 1605, Caravaggio was seen on Via del Corso near the Church of Saints Ambrogio and Carlo carrying a sword and a dagger without a permit. Captain Pino arrested him, but this time, when Caravaggio claimed verbal authorization, he was released. The weapons were returned to him, but the scribe who had taken the complaint made drawings of them.

Just two months later a notary for the Vatican Vicariate, Mariano Pasqualoni from Accumoli, told police that on July 29 he was walking, unarmed, near the Spanish Embassy in Piazza Navona when he received a severe blow on the back of his head from "either a sword or pistol,” according to an eyewitness. The aggressor was surely Caravaggio, Pasqualoni told police, because the two were involved in a quarrel over one Lena, described as "Caravaggio's woman."

The new information alsos sheds light on the quarrel in which Caravaggio killed a man. Like a Los Angeles gang battle, the fight between two groups of four was not spontaneous, but planned. In a pitched battle May 26, 1606, at or near a pallacorda court (an early version of tennis) near Via della Scrofa, two rival gangs of four met and fought. The fight was over neither a bad call during a tennis match or a dispute over a woman, but more likely over a 10,000 scudi gambling debt owed by Caravaggio. During the fight Caravaggio ran his sword through and killed Ranuccio Tomassoni of Terni. Captain Petronio Troppa of the papal troops, a professional soldier whom Caravaggio presumably hired for the fight, suffered a severe sword injury and was arrested and imprisoned; the new details are from his testimony. Arrest warrants were issued for Caravaggio and the others.

Now wanted for murder, at risk of being beheaded, Caravaggio fled Italy, returning only four years later in hopes of a papal pardon. He did not die on a beach north of Rome, but in hospital—yet another hitherto previously unknown detail.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.