The Grande Dame of Italian Cinema

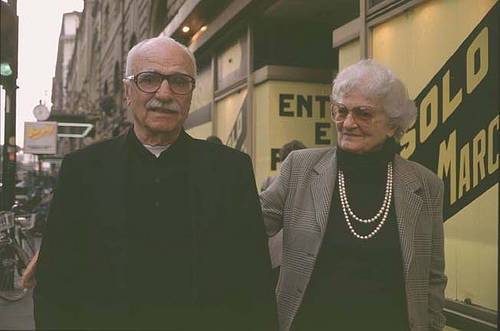

Think of some of the most famous Italian movies like The Leopard, Bycicle Thieves, Rocco and his Brothers, Big Deal on Madonna Street. Think of the setting, the character, the emotions, the historical relevance, the directors…You’ll probably be pretty familiar with them, you might recognize those scenes or at least a poster and perhaps you associate them with the image of Italy you hold in your heart… But do you know whose hand was actually behind those scripts? Who put those words in the characters’ mouth and influenced immensely Italian cinema? The answer is: a highly educated, passionate and witty lady named Suso Cecchi D’amico (born Giovanna Cecchi, 1914-2010).

For her screenwriting was a living, a job, but especially a craft. A pragmatic one. It wasn’t about claiming her authorship. It was about grasping the essence of what the director wanted to do and delivering the words. Her career, in the 30s and 40s, didn’t start as a pretentious call to Art; it was similar to what her character pursued: a realistic endeavor with a touch of culture, humor and awe.

A true artisan trusted by directors such as Visconti, Antonioni, Monicelli, Rosi. A chamelion, to a certain extent, in the way she adapted to such diverse styles. A woman, full of life, who became friends with this circle of artists, creating and becoming an integral part of a cultural movement centered around Rome, obviously, but also around the small town of Castiglioncello, on the Tuscan seaside, where a lot of actors, writers, intellectuals and artists met in the summer vacations or wile collaborating on a script or shooting a scene (for example parts of The Easy Life, Il sorpasso by Dino Risi was shot there).

Castiglioncello was Suso’s adoptive city, her true home, a place where her family (Cecchi)met another prominent Roman family the D’Amico, creating everlasting friendships and allowing her to meet the love of her life Fedele D’Amico. Suso grew up during the wars but her education and upbringing was a perfect contrast to the cultural and actual impoverishment of Italy during those years. As the golden age of Italian cinema flourished in fact, behind there was always somehow the touch of Suso. Who helped making Italy flourish, without ever considering herself a cultural icon, a VIP, just an essential piece in a well-constructed clockwork.

Born in Tuscany from Emilio Cecchi, a writer himself and the painter Leonetta Pieraccini, it’s obvious that the artistic genes were already in her blood. Her writing is deeply filled with literature and high-brow culture, theater and erudition but her true talent is in making things simple, in finding comedic elements in tragic situations, in bringing out of others and other things what matters instead of super-imposing a theme or a pre-fixed idea in them.

As she explains herself in a documentary, directed by Luca Zingaretti and Margherita D’Amico (her granddaughter) it’s important to recognize that cinema, screenwriting has its own rules and adaptation is truly a form of Art in itself. Bicycle Thieves was a short story without a clear dramatic story purpose, nor the ending that we all come to know and love. Those are the essential touches of a screenwriter. Same goes for The Leopard, a beloved Italian classic, a historical novel for which Suso had to incorporate the symbols and descriptions of the book into a scene and translate them into visual emotions.

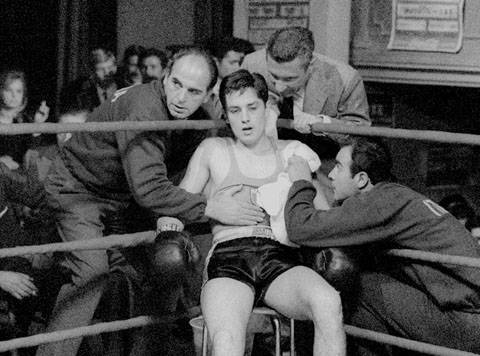

Unfortunately Suso Cecchi D’Amico died in 2010, along with another giant of Italian cinema Mario Monicelli, a few months before him. To honor and discuss her life achievements, ideas and influences, her son Masolino and her daughter Caterina, as well with Antonio Monda, journalist of La Repubblica and NYU professor, held a panel at Casa Italiana Zerilli-Marimò where many people, students and journalists gathered on December 1st, 2010. During the evening a short documentary (by Luca Zingaretti, 2007) of interviews to her shot in Rome and Castiglioncello was screened, as well as pictures of her, clips from her movies that were then discussed and as a homage to Mario Monicelli, Big deal on Madonna Street, a movie on which the two of them collaborated.

Another crucial collaboration in her career was significant as an important bridge between the two worlds. As her son recalled she was asked to contribute to the script of Roman Holidays with Gregory Peck and Audrey Hepburn. Her task was to “make it more Italian”, meaning that she had to infuse realism, certain expressions, turn the real Rome in more than a background to a the rom-com structure of the original script.

Suso gave during her life and indirectly during this event important advices to writers: she worked hard, methodically, she wrote something if she truly liked it, she did a lot of research, traveled to see how story actually happen. She wasn’t possessive of her work. She made it part of her life, never compromising, never turning it into a nerve wrenching task. She worked with her type-writer on her knees, not in her room. She adapted to directors but here and there let her voice emerge.

In the documentary she tells stories about her generation of writers, directors, her peers and her family that in Italy is linked to a certain highly educated group of people in Rome. She talks about that sense of a new beginning, of a honesty found only when not trying so hard to become someone one is not. She jokes a lot, with her dry humor and cynicism but she brightens up when recalling her first love, how young and excited they were while spending those long months in Castiglioncello, living through wars and cultural changes, writing and doing what they loved, meeting people that were like soul-mates for her, intellectuals with deep and complex ideas about music, art, movies, politics and life.

The documentary ends with kind of her joyful comments and yet a honest resignation about the state of modern Italian cinema and Suso seems to imply that back then young people had really different values, a culture that was a lot less mundane.

Although young people might be standing on the shoulders of giants, such as Suso herself and there was a golden age hopefully there can always be a new one.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.