Between Faith and Guilt

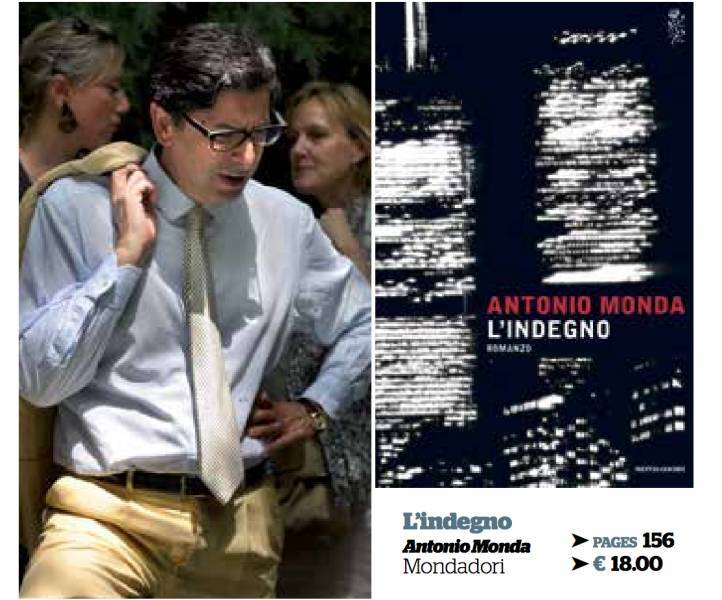

As with previous volumes, the cover is immediately striking, featuring an intense and blurry shot of New York’s Twin Towers. Written as an impassioned monologue, L’indegno examines the complicated relationship between faith and guilt.

A very tortured man

Abram Singer is a priest, a man who has chosen to dedicate his life to God and the Catholic faith. Conceived during a brief but intense affair between his mother and an artistic drifter named Nathan, little Abram will be raised by his mother and never know his father. Despite the Jewish origins attested to by his name, Abram decides to become a practicing Catholic like his mother, enrolls in a seminary, and eventually pursues a career as a pastor in bustling 1970s New York City. His choice may be prompted by his search for a male role model, by the fact that he has never had someone whom he could call “father.”

Abram is a good priest. He patiently hears confession, delivers vivid and passionate homilies and helps the needy. Yet he is also a very tortured man, constantly striving to be virtuous yet prey to temptations of the flesh. When earthly love enters his life, it causes him to break his vows, to renege on the very meaning of his mission.

Enters sweet Lisa

Lisa, the object of his affection, will lead him to commit sins, including lying and stealing.

Abram is overwhelmed by the drama and sense of absolute evil he experiences as a man living in sin, as someone who allows the world to drag him to the brink of eternal damnation, which shame supplies the novel with its potent title. His spiritual struggle is metaphorically reflected in a boxing match he watches in his parish refectory with three of his fellow priests, a young Jamaican student, and two nuns. The match happens to be the historic Rumble in the Jungle between the thirty-four-year-old challenger Muhammad Ali and the world heavyweight champion George Foreman. Round after round, Abram grows more and more excited watching the feather-footed Ali and the powerful Foreman. In the end Ali’s cunning prevails over Foreman’s blind rage.

What upsets Abram so much is the metaphorical equivalent of David versus Goliath, the clash between good and evil, faith and sin. The clash is the source of his morbid suffering, morbid because he can’t stop sinning or lusting after women or acting on his lust. There had been women before Lisa, but then the attraction was purely physical, nothing more. Instead, since the first time he met her, Abram has been deeply drawn to the young volunteer, who stimulates him intellectually with her talk of the Scrovegni Chapel, of Botticelli and Bronzino, Pontormo and Lotti, of the beauties to be found in art. Sweet Lisa loves him unconditionally. She accepts the fact that he is and will remain a priest. She doesn’t ask him to abandon the Church. So strong is her love that she is willing to give up their unborn child, choosing to commit the sin Abram’s mother had refused to commit, bearing him into the world despite the knowledge that her son would never have a father. And cowardly Abram does nothing to challenge Lisa’s decision. On the contrary, he celebrates mass – to his shame and horror – the day after.

Profound solitude

Then one day Lisa is diagnosed with cancer, a sickness that for Abram is both a punishment and a means to expiate his sins... But we don’t want to spoil the whole book. Suffice it to say that the finale is bittersweet, leaving the reader with a taste of Abram’s solitude, the book’s leitmotif. It is a profound solitude, one experienced in New York, a “city of loners,” as Abram calls it. Before he becomes a priest, we see him as a young man assisting in the construction of the Twin Towers, symbol of a city that challenged the sky, which people believed would last forever. We see him at 21, the city’s famous fancy restaurant, or in front of Studio 54. We also see him in his little room in the shabby church. Wherever he is, Abram is alone and tortured, incapable of living life lightly, conscious of his inability to change the world and, more importantly, himself – a human made of mud and spirit, condemned to be what he is.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.