You are here

Articles by: Julian Sachs

-

Events: ReportsAn exhibition of photographs by Ralph Toporoff taken on the set of the film.Also on view, two original posters of the film, courtesy of Posteritati.

Curator: Maria PolitanoCo-curator, Andrea De FuscoThe opening will include the screening of A Dying Breed: The Making of The Leopard, an hour-long documentary featuring interviews with Claudia Cardinale, screenwriter Suso Ceccho D’Amico, Rotunno, filmmaker Sydney Pollack, and many others, produced by the Criterion Collection, followed by a Q&A with Ralph Toporoff.

-

The Metropolitan Opera is a little more Italian, this year. The big news this summer was that, due to health reasons, Music Director James Levine was handing the position of Principal Conductor to Fabio Luisi, already Principal Conductor of the Vienna Symphony and future Generalmusikdirektor of the Zurich Opera. He was already scheduled to conduct Massenet's Manon and La Traviata in the spring, but had to take over Levine's Don Giovanni and Siegfried this fall. Levine is still Music Director and is still scheduled to appear regularly in 2012.

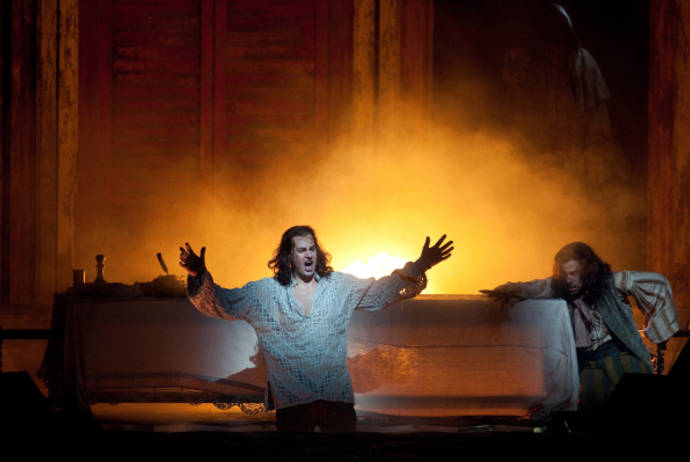

Meanwhile the season has begun. The opera chosen as the season opener (September 26) is

Donizetti's Anna Bolena, his first success back in 1830, eclipsed in time by his common repertoire works Lucia di Lamermoor, Don Pasquale and L'Elisir d'amore. In fact, this is the Met premiere of the work, entrusted to the expert hands of Marco Armiliato, by now a veteran of everything Italian at the opera house. Anna Netrebko stars as the unlucky heroine, decapitated by her husband, King Henry VIII (Ildar Abdrazakov) in order to marry his third wife, Jane Seymour (Ekaterina Gubanova), Anna's lady-in-waiting.

The production was directed by David McVicar, whose successful production of Il Trovatore in 2009 has been a constant presence during these past seasons. McVicar was the right choice for Anna Bolena, since the opera calls for the kind of elegance and fluidity that the director had demonstrated in his previous work. Premiering such an opera at the Met with a more contemporary approach would probably not have worked as well. McVicar uses massive walls to depict Anna's solitude and confinement (both physical and mental), moving them around to allow changes in locations (including a scene in the woods where trees suddenly sprout down from the elegant palace ceilings), and literally uprooting the whole set for the beautiful climactic final scene in the dungeons, where Anna faces execution while, off stage, the new Queen is being crowned.

It is remarkable to notice that until October 27 (the opening night of Robert Lepage's new production of Wagner's Siegfried), every performance of this season will have been in Italian. Also, for a whole month after that, only Siegfried (German) and Satyagraha (English) will be in any other language. Among the more common Italian repertoire on display is Bartlett Sher's popular 2006 production of Rossini's Il Barbiere di Siviglia, always an audience favorite, led as before by Maurizio Benini, a fantastic conductor when it comes to early 19th-century Italian opera.

On stage, Swedish baritone Peter Mattei enchanted the audience in the title role, countered by the expert Italian buffo bass Maurizio Muraro, who will be back this winter as Sulpice in Donizetti's La Fille du Régiment. Mezzo-soprano Isabel Leonard was terrific as Rosina,

contributing to the top-notch acting of the whole cast, with the substantial contribution of guest artist Rob Besserer, in the mute comic role of the servant Ambrogio, gaining the most laughs from the house.

Another new production, this season, is Mozart's dramma giocoso Don Giovanni, conducted by Luisi, who is also providing the harpsichord continuo. Mariusz Kwiecien was supposed to star as the famous ladies’ man, but he injured himself during the dress rehearsal, and is being replaced in the first performances by Mattei, borrowed from the Barbiere cast. In the opera he is pursued by one of his ex-lovers Donna Elvira (Barbara Frittoli), his enemies Donna Anna (Marina Rebeka) and Don Ottavio (Ramòn Vargas), and is brought to his demise by the ghost of the late Commendatore (Stefan Kocan). Through all this he is accompanied by his unhappy servant Leporello, sung by the terrific Italian bass-baritone Luca Pisaroni.

Pisaroni was present at NYU's Casa Italiana Zerilli-Marimò on Friday, October 14, for the series Adventures in Italian Opera with Fred Plotkin and spoke about his formative experience and his approach to baroque opera and to Mozart's music. "In Italy, if you don't sing Puccini, Verdi, Bellini, Donizetti, you're not considered a real singer", he said. "My voice teacher at the conservatory wanted me to sing Zaccaria [from Verdi's Nabucco] in my third year", adding that he though he would wind up singing Wotan by the fifth. He explained that the repertoire he sings allows one to grow without damaging the delicate instrument that is the human voice. This is thanks to the lighter orchestration and the lack of sustained notes in the high register.

About playing Don Giovanni's servant, Pisaroni suggested that the role is successful when the singer conveys how much Leporello enjoys being the servant, conveying the idea that - as much as he might wish it - he will never be like his master. "His life has a meaning because he lives it through Don Giovanni", he said. Don Giovanni, he added, is the engine of the opera and changes the lives of the other characters. "I don't believe in the happy ending. When he dies everybody has a sense of loss".

The new production, directed by Michael Grandage, at his Met debut, is smart and functional, alternating tight proscenium moments such as the Act I duel and the Act II sextet with wider spaces for the scenes with the chorus and the two finales. The large sets by Christopher Oram, rows of tall condominium-style buildings enclose and release the space as if they were a curtain, while the final scene, in which Don Giovanni is dragged to the fiery pits of Hell is achieved with pyrotechnics.

Peter Gelb's greatest achievement as the Met's General Manager is certainly the successful High Defenition live broadcasting of the season's highlights around the world. This year, the Italian film distribution company Nexo Digital announced that it would broadcast eleven performances from the Met in forty Italian cinemas. For those who read this from the Bel Paese, www.nexodigital.it includes all the necessary schedule and location information.

A terrific season awaits us at the Met, and it is exciting to know that opera lovers around the world are gathering to take part in it, even (and finally) in the land that gave birth to this art form over 400 years ago.

-

Art & Culture

Art & CultureVanity Fair has described it as "a poignant, fascinating, linguistically rich book". From the Land of the Moon is the first English translation of a novel by Sardinian author Milena Agus, published by Europa editions.

Agus published her first work, Mentre dorme il pescecane, in 2005, which was soon followed by Mal di pietre in 2006. It was the latter that won her the 2008 Zerilli-Marimò/Città di Roma Prize for Italian Fiction, awarded in New York at NYU's Casa Italiana Zerilli-Marimò on December 9, 2008. The prize consisted of a grant of $3,000 and, more importantly, a large financial contribution for the translation and publication of her book in the United

States,

Interviewed by i-Italy at the time, she had said, "I would like the passages in Sardinian dialect to be left just as they are. Maybe the translators could add the English version in a footnote at the bottom of the page. This is what they did in France and I find it to be the best solution possible. I think that the Sardinian language lends a sort of intimacy, a familiarity to the characters, which is unknown to their Italian counterparts."

Her wish was respected and this edition leaves the Sardinian passages untouched. This is the 7th novel translated from Italian into English and published in the United States thanks to the literary prize, an outstanding result considering the great difficulties for foreign authors (Italian in particular) to be published in the across the Atlantic. The American public has now a great opportunity to discover a new foreign author and reward the hard work that Casa Italiana Zerilli-Marimò and the Casa delle Letterature di Roma put in towards facing the challenge of spreading contemporary Italian fiction in America.

-

Art & Culture

Art & CultureBetween Sunday, April 10, and the following Sunday, April 17, a remarkable number of concerts ended with the public going wild and giving the performers well deserved standing ovations and endless rounds of applause. The recipients of these waves of love and approval were two of the greatest active conductors, James Levine and Riccardo Muti, both of whom have recently seen their activities seriously threatened by health problems.

On April 10, Levine led his Met Orchestra at Carnegie Hall in a performance

of Schoenberg's Five Pieces for Orchestra, Brahms' Symphony No. 2, and Chopin's Piano Concerto No. 1, featuring the Russian pianist Evgeny Kissin. The great conductor, who will turn 68 in June, had recently made the papers for having left his position of Music Director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra and having delegated almost 50% of his Met engagements to others, owing to health problems.

On Sunday he needed a walker to cross the stage and a cane to climb up on the podium. But when he set those items aside and wielded his baton, it was as if nothing were wrong. The execution of Schoenberg's Op. 16 from 1909 was unbelievable. The piece was written in the composer's intermediate phase between his tonal and 12-tone periods, and Levine did a masterly job in expressing the melodic freedom of the work, dragging the captivated audience along in its sudden bursts of fortissimi and spine-chilling pianissimi.

The big star of the evening, though, was the 40-year-old Russian virtuoso Evgeny Kissin, who enthralled the public with a breath-taking execution of Chopin's first Piano Concerto, written at the age of 19. In perfect symbiosis with the orchestra, Kissin offered an unforgettable example of how to tackle the Polish composer's early works with strength and dynamic range. Maybe too much so, one might argue, considering Chopin's reputation as weak and quiet, delicately performing his fast and complicated passages on pianos that did not yet have cast-iron innards. After a long standing ovation, the pianist treated the public with a solo encore, Chopin's B-flat minor Scherzo, Op. 31.

Back in their natural habitat, at the Metropolitan Opera, Levine and his orchestra performed a run of Berg's first opera, Wozzeck, reprising a 1997 production by Mark Lamos and featuring the amazing baritone Alan Held in the title role. Making it sound really easy, Levine unraveled the intricate score for the audience with precision and expression, helped by the Weimar-esque sets and lighting and an ideal cast that also included Waltraud Meier as Wozzeck's companion Marie, Walter Fink as the Doctor, and tenors Gerhard Siegel and Stuart Skelton as the Captain and Drum Major, respectively.

Also, Levine was preparing for a run of performances of Wagner's Die Walküre, in Robert Lepage's new production, which opened on Friday, April 22.

Meanwhile, back at Carnegie Hall, the long-awaited three-day

visit of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, led by their new Music Director, Riccardo Muti, was taking place. Muti, who will turn 70 in July, was forced to bow out of his first month of residency due to exhaustion, and when he finally returned to Chicago in the winter for three weeks of concerts, he collapsed on the podium during a rehearsal, which resulted in multiple fractures to his jaw and cheekbone and prompted doctors to install a pacemaker. Considering his complete rehabilitation and his triumphant return to success, as well as a youthful choice of “pure energy” repertoire, a joke is circulating involving the Maestro asking his doctors to set the pacemaker on “High”.

The ailments seemed completely consigned to the past when Muti charged to the podium, smiling, amid the cheering of the audience on his first night at Carnegie Hall, on Friday, April 15, to perform one of Verdi's masterpieces, his second-last opera, Otello.

The hall was completely sold out. The stage was overloaded by the large orchestra, the Chicaco Symphony Chorus, the Chicago Children's Choir, and a cast of singers that included the excellent Latvian tenor Aleksandrs Antonenko in the title role, veteran Carlo Guelfi as the evil and cunning Iago, and an amazing Krassimira Stoyanova as the innocent Desdemona, who delivered an unforgettable performance that outshined her colleagues.

From the opening orchestral explosion it was clear to all the listeners that this was going to be a real treat. Like Verdi’s Messa da Requiem (1874), Otello is as much a choral work as a straight opera, and this allows it to be experienced at its fullest even in a concert performance, in the same way that one could experience Beethoven's Ninth Symphony or Berlioz's Damnation of Faust. Verdi puts everything into the music: movement, feeling, chaos and madness. One wants to seek cover during the sublime storm and battle that opens the opera, just as clearly as one wants to peek out from the previous shelter when the clouds have dissipated in the second half of Act I, and witness the tender exchange between Othello and Desdemona.

But as much as Verdi has put into this indescribably beautiful

work, it takes an expert to extract the hidden nuances that are necessary to grasp the full potential of its drama. There is no conductor alive better than Riccardo Muti at this task. Italian opera is his domain and Verdi is his stronghold. Nobody present at the performance will ever be able to forget it.

The clarity and passion the CSO expressed on Friday night reverberated throughout the following two concerts and, personally, Otello kept looping in my mind while attending Saturday's performance of Berlioz's Symphonie fantastique and Lélio.

Moving back in time from Otello, the harmonically revolutionary character of Berlioz's symphony – which he wrote in 1830, at age 27 – was almost muffled, but the execution certainly was not. Muti is also a great Berlioz interpreter, and he knows how to get the right sound from the orchestra. Lélio, a fairly boring composition, creates a somewhat anti-climactic juxtaposition with the symphony, but Muti likes to perform the two works consecutively, as Berlioz wished. In recent years, he has done this with the help of the most famous French actor alive, Gérard Depardieu, who offered an entertaining reading of the text, written by the composer himself, albeit with a strong Shakespearean influence.

The final concert – the least unusual of the three - took place on Sunday afternoon and featured Cherubini's Overture in G Major, Liszt's Les Préludes, and Shostakovich's Symphony No. 5. It was originally supposed to have featured a work by Varèse and a new piece commissioned by the CSO, but that program had to be skipped by the conductor during his rehabilitation. A rarely performed work, Cherubini’s overture was the real treat of the program, especially since Cherubini is another Muti specialty.

In conclusion, every week of classical music in New York is a special week, and that is what makes the city the musical capital that it is. But sometimes there are peaks. Carnegie Hall boasts the best acoustics in the city and among the best in the country and beyond, and by hosting these two great conductors who have recently reminded us of their own mortality and human frailty in general, it gifted us with a little extra slice of temporary infinity.

-

Art & Culture

Art & CultureOn March 24, the Metropolitan Opera staged, for the first time, Le Comte Ory, Rossini's only French comic opera, in a production directed by Bartlett Sher, featuring Juan Diego Flórez in the title role, Diana Damrau as Countess Adèle, and Joyce DiDonato as Isolier, the Count's page. Maurizio Benini led from the pit.

In the story, Ory, a womanizer, tries to take advantage of the Crusades to seduce the many lonely wives who have been left behind by the soldiers fighting in the Holy Land. Dressed first as a hermit and then as a nun, the Count plots to win over Countess Adèle, who lives secluded in her castle, but runs up against his young page, Isolier, who is also in love with her.

In this production, Isolier, sung by DiDonato, hops on stage half-way through Act I in leather traveling clothes and boots, with a long flow of curly brunette hair, fueling the remainder of the performance with romance and true passion.

Born and raised in Kansas, DiDonato studied at Wichita State University, where she became interested in opera. She began winning important competitions during the 1990s and in the course of the last decade quickly ascended to the Olympus of stars of the bel canto repertoire and beyond, debuting at New York City Opera in 2003 in Jake Heggie's Dead Man Walking. Her Metropolitan Opera debut took place in the 2005-2006 season as Cherubino in Le nozze di Figaro, and since then she has become a frequent performer on the main New York operatic stage.

On March 30, she shared the small stage of New York

University's Casa Italiana Zerilli-Marimò with music expert Fred Plotkin in his ongoing series, Adventures in Italian Opera with Fred Plotkin. In front of a full house the two participants, who had never met before, discussed many aspects of the world of opera, and the mezzo-soprano gave a demonstration of her solid knowledge, attention to detail, respect for the art form, personal modesty, and terrific sense of humor, which greatly entertained the public.

Dressed in pants and leather boots – almost identical to Isolier's garb in the current Met production – the singer began by speaking about the current musical scene in Kansas and the influence that that state had on her attitude towards her work:

“One of the things that has served me really well growing up in the Midwest is that I'm not afraid of work and I'm very aware that it takes a lot of people to produce something. I've never shied away from the workload involved in starting a career and building a career, and hopefully maintaining a career at a high level.”

The singer explained that today we are more specific about voice types, but that actually a mezzo-soprano is a voice type that can fill the gaps, touching very low notes as well as reaching well into the soprano range.

“I can't stay in [the soprano] tessitura; it is where I am not most comfortable. I can go up there with a certain degree of success, but I can't stay there. For example, I would never sing Donna Anna [in Don Giovanni], but I have sung Donna Elvira rather successfully in the transposed version of [the aria] “Mi tradì,” which Mozart actually did, taking it down a half step.”

The audience was particularly fascinated when the diva gave a demonstration of the work involved in figuring out the characterization of a role. “It's in the music. All the cues for interpretation are mostly in the score,” she explained, pointing out the difference between singing a role in a Haendel opera – where there is almost no notation for the singers beyond the bare notes – and performing twentieth-century operas, in which composers tend to mark everything they require of the singer. She added that in performing Rossini, there is usually more than one version to choose from, since in different cities he would adapt his works to particular voices. “That's the great freedom of this kind of music. I get to put my signature on it.”

A few nights earlier, DiDonato had sung a Rossini aria in front of a Broadway crowd, trying to transmit the composer's audacity in the vocal line. The public went wild. “My mantra is that if you give people the good stuff, they get it.”

A brief discussion followed about the upcoming run of Strauss' Ariadne auf Naxos, which will feature DiDonato in the first act as the Composer, alongside Lithuanian soprano Violeta Urmana in the title role, a rare occasion in which such different voices can come together. Urmana will be Fred Plotkin's next guest at Casa Italiana, on April 13.

The audience was able to listen to a few examples of Ms. DiDonato's repertoire, especially from her Diva/Divo album (EMI/Virgin Classics), a collection of arias featuring different characters, both male and female, one of the peculiarities of the mezzo-soprano repertoire. While commenting on her performance as Romeo in Bellini's Romeo e Giulietta, Plotkin mentioned having seen her perform the role in Paris opposite a seven-month pregnant Anna Netrebko. “I'm really good at those pants roles,” joked DiDonato.

And a pants role is what DiDonato is performing now at the Met: a role that, character-wise, lies halfway between Romeo and Cherubino. Like Cherubino, Isolier is a page, but a slightly older one, who not only longs for a woman but is loved back by her.

Rossini wrote his second-last opera over a fifteen-day

period in 1828, at age thirty-six, one year before Guillaume Tell and his subsequent retirement from the world of opera. By then he had thirty-nine titles behind him and was easily the most popular composer in the genre. At the time, he was living in Paris, having been commissioned by one of his fans - King Charles X - to write five operas a year as music director of the Théâtre des Italiens.

However, Ory premiered at the Opéra in Paris, which usually staged serious operas. Although the work is a farce, the music follows the more canonical alternation of long set-pieces and accompanied recitatives, unlike the shorter pieces and spoken dialogue of the opéra comique genre. As frequently happened with Rossini's works, a large amount of the score was taken from a previous opera, in this case Il viaggio a Reims, composed three years earlier for the coronation of Charles X.

The opera was a huge success with both public and critics, and Hector Berlioz declared that the second act love trio was Rossini's masterpiece. The trio involves the tenor, dressed as a woman, seducing the mezzo-soprano who is playing a young man dressed as the soprano, while the real soprano remains hidden.

The current Met production, like the world premiere 183 years ago, has been a success. The singing is outstanding, with the three lead singers tackling their roles with agility, humor, and flawless virtuosity. Benini and the Met orchestra are terrific as usual, but the production seems ready to fall apart under the weight of its tastelessness. Bartlett Sher is a remarkable director whose two previous productions at the Met – Rossini's Il barbiere di Siviglia and Offenbach's Les Contes d'Hoffmann – were clever and never felt overdone.

Ory, on the other hand, has ups and downs. The concept behind the production is meta-theatrical, with a small, commedia dell'arte-style, candle-lit wooden stage placed in the middle of the real stage, and with the performers entering and exiting in full view, offering staged glimpses of back-stage frolics and vintage stage management, such as wind and thunder machines and hanging candelabras. This is all reminiscent of Giorgio Strehler's classic production of Goldoni's Arlecchino servitore di due padroni with the Piccolo Teatro di Milano, but it completely lacks Strehler's taste in never carrying the farce too far.

Sher never misses the opportunity to deliver some sort of joke, whether it is someone being knocked over or grabbed in the private parts. None of these situations would, by itself, flunk the production, but the overload kills it. The sets, by Michael Yeargan, are well done and fit in beautifully with Sher's concept, and, of course, it is the result that counts: the musical quality is outstanding and the audience loves the whole thing.

-

Art & Culture

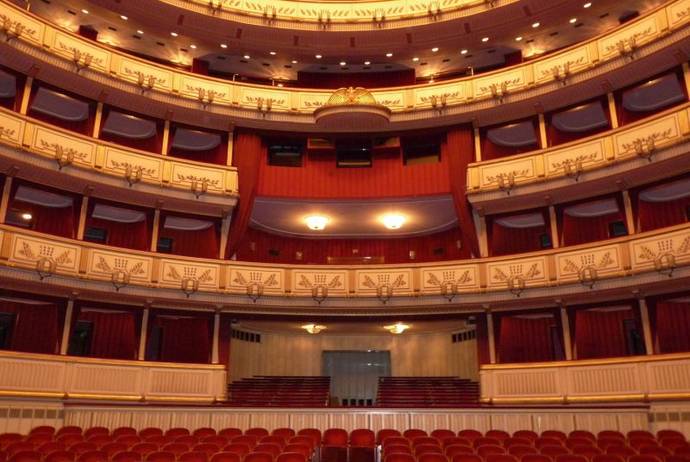

Art & CultureI was born and grew up in Italy, and since I am an opera fan, I often meet other opera fans from other countries, especially the United States, who think of Italy as the land of opera, a country in which this art form plays a central role in the daily life of its citizens and maintains an important status among forms of entertainment. Unhappily, it always pains me to explain that this is not so.

It certainly used to be so. Italy has an amazing number of opera houses that are now either boarded up or converted into something else. Most Italians haven't got a clue as to what this art form is, and I wouldn't be surprised to learn that their only operatic experiences come from the background music in television commercials.

Being a young opera lover in Italy is not like being a film buff; it means being an outcast, someone who loves something ridiculous, boring, elitist, and expensive. Why do most Italians think this? I believe it is because there is no music education in most Italian schools, which will make it impossible for future generations of adults to be as informed about opera as they will be about art history – which is mandatory in most schools – and cinema, which has played an important role in their daily lives since childhood.

The website www.operabase.com, a public site that has been documenting operatic activity since 1996, with over 260,000 performances on file, recently published a page of statistics regarding the world of opera, and it sheds some light on Italy's position.

According to statistics based on 23,000 performances, worldwide, during the 2009-2010 opera season, 7,892 (more than a third) of them took place in Germany. The United States is a distant second (1,935); Austria follows with 1,426 performances. Italy is still high on the list – in fifth place, with 1,206 performances during the season.

But this statistic does not take into account the size and population of each of these countries, which is why OperaBase also published a per capita statistic, resulting in Austria's amazing supremacy, and Italy coming in seventeenth, with Lithuania.

As far as cities are concerned, Vienna is by far the most operatic city in the world, with its four main opera houses producing most of its 617 performances, and it is followed by Berlin, with 521. The amazing fact is that among the top 100 opera cities, 47 are in Germany, 7 are in Austria (I can't even name 7 cities in Austria), 5 each in Switzerland and Poland, and only 4 in Italy (Milan at #54, Rome at #71, and Trieste and Verona barely making it into the top 100, respectively at #95 and #99).

Italian opera itself, though, still rules. Based on counts of performance runs over the last five seasons, our own Giuseppe Verdi is in the lead with 2,259 productions, followed closely by Mozart at 2,124 (although his popular singspiels, The Magic Flute and The Abduction from the Seraglio, are included); Puccini lags slightly behind at 1,732. Four of the top ten composers are Italian, alongside two Germans, two Frenchmen, an Austrian (Mozart) and a German/Englishman (Handel); these last two, of course, produced mainly Italian operas. In recent decades there has been a constant rise in interest for bel canto operas, as the high positions of Rossini (5th), Donizetti (6th), and Bellini (16th) demonstrate.But Italian opera today is visibly in decline. In a list of the most performed living composers, only six Italians appear in the top 100, in contrast with 21 in the previous statistic.

As far as the operas themselves are concerned, The Magic Flute leads the way as the most performed work, followed closely by La Traviata, Carmen, and La Bohème. Mozart's three Da Ponte operas – Le Nozze di Figaro, Don Giovanni and Così Fan Tutte – are respectively 5th, 7th, and 11th. As expected, Puccini is present in the Top 10 not only with Bohème but also with Tosca and Madama Butterfly. Rossini's Il Barbiere di Siviglia (#9) completes the list. I was surprised to note that after La Traviata (#2), Rigoletto (#10) and Aida (#13), the most performed Verdi opera is Nabucco (#17), ahead of the popular Il Trovatore (#23).

I thought it would be interesting to share some of these statistics, but of course we must keep in mind that there are many other factors involved that produce these results. The main examples are production costs and talent requirement: a small opera company (and many large ones, as well) are able to stage The Magic Flute or Il Barbiere di Siviglia much more easily than a more massive opera such as Wagner's Siegfried (#50). This can be demonstrated by searching for German operas down the list, where one encounters first Humperdinck's fairy tale opera Hänsel und Gretel (#14) and Wagner's Der Fliegende Holländer (#25), which precedes his most representative works and is, in fact, easier to put on stage. It is after the Top 30 that one finds two one-act operas, Strauss' Salome (#32) and Wagner's Das Rheingold (#33), Beethoven's Fidelio (#34) and, finally, Die Walküre (#36).

I feel that in many parts of the world, opera is as alive as it ever was, and it is becoming more and more accessible to everyone, also thanks to new technological achievements in broadcasting. On March 12, Riccardo Muti, conducting Nabucco at Rome's Teatro dell'Opera, gave an encore (which he rarely does) of the “Va', pensiero” chorus after having criticized the government for cutting Italy's art budget (Fondo Unico per lo Spettacolo), the already feeble lifeline that barely keeps Italian opera companies alive. According to Associated Press, the conductor turned to the audience that was yelling “Bis!” and conceded the encore on the condition that the public sing along in the name of culture and patriotic spirit.

One hundred fifty years after the unification of Italy, Muti said, “I don't want, today, in 2011, for Nabucco to become a funeral hymn to culture and music. I tell the chorus, the orchestra, the technicians to keep up their work, but their salaries don't even let them pay their bills at the end of the month. Culture is seen as some kind of aristocratic bonus by too many politicians, instead of being intrinsic to the nation's identity.”

I hope that steps will be taken soon to re-establish music in general and opera in particular as “intrinsic to the nation's identity” by re-introducing them in the schools, on television, and in the national budget.

-

Art & Culture

Art & CultureOn February 22, a large public gathered at Casa Italiana for the popular series Adventures in Italian Opera with Fred Plotkin, which was supposed to feature the soprano Aprile Millo, who was ill and had to cancel. At the last minute, Fred Plotkin came up with a Plan B lecture entitled “Voci Verdiane. The Art of Singing Verdi”.

Plotkin began by telling everyone that he had just returned from Parma – Verdi's home city – and the “Voci Verdiane” festival. Faced with the question “What is a 'voce verdiana'?” he said that there is no single style necessary. Considering that the composer wrote 26 operas over 57 years, it would be impossible for there to be a one way to perform his works. Not only did styles change over Verdi's lifespan, but the nation itself changed many times.

The author of Opera 101: A Complete Guide to Learning and Loving Opera singled out the essential aspects of singing Verdi and accompanied each one with audio selections. He chose Pavarotti's “Sì, lo sento” from I due foscari and Leonie Rysanek's “Nel dì della vittoria” from Macbeth as examples of “Unmistakably Verdian” voices, where the singers understand the music and the words, which led to the aspect of “Language”. The public was offered recordings of Licia Albanese singing “Teneste la promessa” from La Traviata and Alfredo Kraus singing “La donna è mobile” from Rigoletto. The speaker explained the importance of using the breath for acting as well as for support, especially in rendering a character like Violetta – at death's doorstep, at that point of the opera.

Historically, the language in Verdi operas was fundamental for many reasons. Most Italians were illiterate at the time and learned world literature through opera, especially from Verdi's, since he was very close to European literature, and used libretti based on authors such as Shakespeare or Hugo. Also, Verdi wrote two operas on French libretti, Don Carlos and Les Vepres Siciliennes, from which Plotkin selected a recording of Beverly Sills singing “Merci Jeunes Amies”.

Speaking about “Interpretation”, Plotkin explained that singers have to understand the “tinta”, in other words the particular hue, of the opera, since Verdi wrote all kinds of operas with all kinds of different hues. La forza del destino has a rather dark and cold hue, having been written during the composer's stay in Saint Petersburg. The opera expert chose two drastically different interpretations of the “Pace, pace” aria, one very slow and contemplating by Aprile Millo, and one much faster and contained by Eileen Farrell, mainly known as a Wagnerian singer, but perfectly capable of adapting her voice to the needs of Verdi operas.

The final aspect, more complicated to define, was what Plotkin calls the “Imperative”, the ability to convey the specific moods in certain moments of the music, in other words what allows a listener to understand what is happening on stage and what the characters are feeling even without understanding the words. The excerpts chosen were Eileen Farrell singing “Teco io sto” from Un ballo in maschera and Zinka Milanov singing the “Miserere” from Il Trovatore with Jan Peerce.

Finally, the speaker tied all the threads together and played examples of how the different aspects are balanced in a great Verdian voice and a supreme artist. He chose baritone Tito Gobbi performing two completely different late-Verdi roles, Falstaff's “Quand'ero paggio” and Jago's “Credo in un Dio crudel”, from Otello, and Leontyne Price's beautiful “O Patria Mia” from Aida, after which the public dedicated a very long applause to the eloquent speaker, who reminded everyone present that the following Adventure in Italian Opera with Fred Plotkin will take place on March 30 and will feature the great Mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato.

-

Lorenzo Iosco

Lorenzo IoscoOn February 23, 25 and 27, the London Symphony Orchestra will be in New York performing Mahler symphonies at Avery Fisher Hall, led by their Principal Conductor Valery Gergiev. Sitting in the wind section will be Principal Bass Clarinet Lorenzo Iosco, an exceptionally talented young Italian musician who grew up in the hills of Tuscany and is now traveling around the world with one of the greatest orchestras, as well as performing with the orchestra of the Teatro Real in Madrid. I-Italy had the opportunity of asking him some questions on the eve of his third visit to New York.

What brought you to music and the clarinet?

The choice of clarinet was made for one simple reason: my grandfather was First Clarinet of his town band and until I turned six (after which I moved to Tuscany with my parents) I listened to him every day playing opera tunes and songs from the 1930s. Wanting to follow in his footsteps, among other reasons, I enrolled in the band of a nearby village, San Giustino Valdarno, choosing to play the clarinet.You are a perfect example of the so-called “fuga di cervelli” [brain drain] which represents today’s cultural class in Italy. What steps took you away from Italy?

After getting my conservatory diploma and gaining experience in the Orchestra Giovanile Italiana [Italian Youth Orchestra], at age 20 I began auditioning for various orchestras and after a few failures, due to lack of experience, I won the audition for clarinet and bass clarinet in the Orchestra Sinfonica di Roma, my first real job! There I gained my first true symphonic and operatic experiences. I have many fond memories of the time spent in Rome and all the people I met in that splendid atmosphere.After a few months I enrolled in a bass clarinet competition at the Teatro Real in Madrid, in a

period of economic boom for Spain and, consequently, for the Spanish cultural scene. I decided to give it a shot, and after a morning spent auditioning I won the seat. Obviously, in Madrid, working conditions and the quality of life are drastically superior to those in Rome, also because the Teatro Real is considered the best opera orchestra in Spain.

But I didn’t feel it was time for me to settle down, so I decided to continue preparing for more auditions. After a wonderful year, playing the most beautiful pages of operatic repertoire of all time (among which Berg’s Wozzeck, Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, Puccini’s Madama Butterfly, Mozart’s Don Giovanni), I thought it would be a good moment for me to return to Italy, more precisely at the Teatro La Fenice in Venice, where a clarinet competition had just been announced. I prepared and went. Here is where my first real disappointment struck, as I failed to pass even the first phase of the competition, the so-called “eliminatory phase”, where the axe falls upon those the jury feels don’t even have the requisites to play in an orchestra. I asked for an explanation and was told that my performance was “exuberant” with “too many dynamic excursions” and that I should continue my studies because they didn’t feel I was ready to work in an orchestra. It is easy to imagine how I felt as my self-esteem plummeted at hearing those words. But I kept wondering if I actually should take such criticism seriously, and if being “exuberant” and these “dynamic excursions” they spoke about actually were flaws, since I strongly believe these are attributes a musician should have.

It turned out that these flaws led me to win an audition and its following trial period with the London Symphony Orchestra. From that moment on I was torn between Madrid and London, until one day, in New York, during a month-long US tour with the LSO, under the baton of the great Valery Gergiev, the whole orchestra unanimously voted to offer me the job of Principal Bass Clarinet, after which I moved to London on a permanent basis, occasionally collaborating with the Madrid orchestra, as well.

This will be the third time you come to New York with the LSO. What do you think of the city and its public?

What can you say about such a fantastic metropolis? Well, first of all it is a city where I would love to live, because of the extraordinary combination and mix of different cultures and ethnicities, co-existing peacefully and respectfully! This is my view of New York, not to mention the consequences this environment has on artistic and cultural activities (and culinary, as well). It is a true capital that represents what the whole world should be like.

As I mentioned before, New York has also a great meaning for my career, since this is where the LSO asked me to join the orchestra officially on a permanent basis.On January 15, 2011, you played your British solo debut, performing Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto, a milestone for every clarinetist. How did it go? Do you have future plans as a soloist?

Although I began my orchestral career playing bass clarinet, I never gave up the opportunity to cultivate the clarinet, the instrument I began with and never abandoned. When I was offered the opportunity to perform the most classic of classics for solo clarinet and orchestra, I tried to take advantage of it to personally get to know this score better, while never abandoning those canons determined by decades and centuries of interpretations. On this occasion I had the luck of working with a new youth orchestra, Kantanti Ensemble, made up of former students of the main schools of London (the Royal Academy, the Royal College, the Guildhall School, etc.), a team with a brilliant and decisive sound, which I hope will continue to grow in the future. After this series of performances, both the orchestra and myself were so satisfied that I was offered another collaboration (possibly for next year), probably performing Aaron Copland’s Concerto.Do you miss Italy? Are there any hopes for its musical and cultural scenes after the government’s recent cuts to the Fondo Unico per lo Spettacolo, the government funding of the public sector of the arts?

Well, I must say that wherever I am I never forget Italy and those who are dear to me, with whom I keep in touch all the time thanks to today’s technologies. Whenever I have a break I get on a plane and visit family and friends, so I don’t feel this separation so badly.

As far as the political and cultural situations are concerned, I don’t miss Italy at all: the two aspects are strongly interconnected and interdependent, and today’s political situation in Italy leaves no hope for a change of course. I believe that a rebirth of hope for the future could only come from a radical and definitive change of the political and social structures of the nation.Being able to travel around the world and see how different countries relate to culture and how orchestras are managed, what are your feelings about your Spanish and British experiences in contrast with Italian and extra-European systems?

My experiences in Italy, apart from my formative years at the Conservatory in Florence and a brief experience with the Orchestra Giovanile Italiana linked to the Scuola di Musica in Fiesole, are limited to my year in Rome and my audition in Venice. The latter was very meaningful for me, because it shed light upon the questionable recruitment systems of Italian orchestras, which allow for favoritism and partiality. Outside of Italy I respect the way orchestras are managed, especially in England, where I found the musicians to be highly concentrated and serious, unlike what in Italy I would refer to as pressappochismo and guaglionaggine [literally ‘sloppy-ism’ and ‘childishness’], even though they try to promote these as ‘creative disorder’ – but they don’t always succeed. -

Art & Culture

Art & CultureDecades before director Sergio Leone, with the fundamental aid of Clint Eastwood and Ennio Morricone, created a new western genre, made in Italy, commonly known as Spaghetti Western, there was Puccini's opera La Fanciulla del West (The Girl of the Golden West). On December 10, 1910, the Metropolitan Opera gave its world premiere, a huge event that involved the greatest operatic names of the day, such as Arturo Toscanini and Enrico Caruso. It marked the first time that an Italian opera was premiered in America and both the attention of the New York public and the price of tickets reached unprecedented levels.

One hundred years later, the Met commemorates this event by reprising the opera, in a Giancarlo Del Monaco production from 1991, starring Marcello Giordani, Deborah Voigt, and Lucio Gallo, and conducted by Nicola Luisotti. For the occasion, the Italian Cultural Institute organized an event coordinated by Prof. Deborah Burton of Boston University, which included the grandchildren of Toscanini and Puccini, musicologist Allan Atlas, music historian Harvey Sachs, as well as Giordani and Luisotti. Del Monaco himself and baritone Lucio Gallo were also present, but as spectators.

The panel was introduced first by the director of the Italian Cultural Institute, Riccardo Viale, who

expressed the importance of this 100th anniversary, simultaneous with the 150th anniversary of Italy's unification. Born in 1858, Puccini lived through the first six decades of his unified homeland, and died, in 1924, during the first phases of the Fascist regime.

After Viale, the podium was taken by Italian Consul General Francesco Maria Talò who suggested that this event was a turning point in the relationship between Italy and New York, the repercussions of which are still felt today, one hundred years later.

Next it was the turn of Sarah Billinghurst, Assistant Manager of the Metropolitan Opera, who explained some of the lesser known stories behind this work - for instance, the fact that Fanciulla was not commissioned by the Met, and that New York's famous opera theater was chosen as part of a bargain with the Ricordi publishing house in exchange for performing the composer's early opera Manon Lescaut in Paris (for the first time) during a tour of the

New York company; also, that Puccini was paid 20,000 Lire (“about 11 euros” joked Del Monaco from his seat) for composing the opera. Actually, if any such comparison is possible, the sum would round off to almost $120,000 of today.

Ms. Billinghurst explained that although the opera was a huge success (there were 19 curtain calls on opening night), the Met only reprised it ten times during its first century. On the other hand, it was the first opera to be performed in the new Met, when it was built in 1966 (during a student matinée; the actual first opera was Barber's Antony and Cleopatra) and this current centennial production will be broadcast live in HD in 46 countries around the world, although sadly not in Italy, which apparently remains technologically impaired.

Finally, the reins were handed to the panel, led by Prof. Burton, the mind and motor behind these centennial celebrations and their relative website, www.fanciulla100.org. After delighting the audience with a 1910 film of Puccini in America (audio and video from two different sources) and a tour of the website and its multimedia treasures, she handed the floor to music historian and Toscanini biographer Harvey Sachs, who moderated a mini-conversation between Walfredo Toscanini and Simonetta Puccini, the grandchildren of the two operatic titans. They elaborated mainly on the relationship between the two artists, and Mr. Toscanini explained that his grandfather referred to Fanciulla as a “symphonic poem”, with the orchestra as protagonist - a view shared by Giordani and Luisotti. Also, Toscanini had made a lot of changes in the actual score while preparing the orchestra, while Puccini was still in Italy. Sachs pointed out that this was not uncommon and that both artists represented an approach typical of their day to the preparation and performance of operas.

Allan Atlas spoke about the very close relationship between David Belasco's original play and Fanciulla's libretto and punched holes in the myth of Puccini's using a piece from that play as the

Minstrel's song. Actually, he explained, Puccini didn't write the theme himself, but it came from a 1904 publication of a Zuni Indian melody, transcribed by Puccini’s friend Sybil Seligman from what was originally a chorus of virgin maidens, arranged by Carlos Troyer. But the real treat was Atlas showing excerpts of the Puccini manuscripts in the various stages of composition, from the early sloppy motive sketches to the more continuous – but still sloppy – successive drafts.

Next, it was the turn of the panel's two artists. Luisotti spoke about the first time he performed Fanciulla as a chorus member in Lucca in 1985, which marked the current production as his own personal 25th anniversary. He also confessed how scary it is to conduct this score, which he considers to be the hardest Puccini opera – a work that can create many difficulties for the conductor. Giordani, on the other hand, is singing his first Fanciulla, and he explained that the role of Dick Johnson is exotic, especially if one is more used to the traditional single-faceted roles of Cavaradossi or Rodolfo. “DJ”, as he calls him, is part of a different culture – for Puccini, but also for the other characters in the opera – and expresses his latino romantic and passionate side within the rough traditional western good guy/bad guy double-sided role.

The public listened carefully to all of these points of view and interacted with the panel, asking questions about the music but also about the issues and legends that surround this opera, such as Andrew Lloyd Webber's supposed plagiarism of Fanciulla in writing his famous Phantom of the Opera and the many stories of Toscanini in rehearsal. Del Monaco took part in the debate as well and explained his personal love for Puccini derived from what he calls his “cinematographic style”, not to be confused with a “movie composer”.

At the end of the Q&A, Prof. Burton thanked everyone present and – with a slight alteration to the libretto’s “Whiskey per tutti!” – announced, “Vino per tutti!”.

-

Art & Culture

Art & CultureThe Park Avenue Armory, built between 1877 and 1881, has become, in recent years, a unique and prestigious performing arts center. By New York standards it is unusual, to say the least: it stands out architecturally as a giant Gothic Revival fortress situated right on Park Avenue, across the street from the Italian consulate and cultural institute, and its 55,000-square-foot drill hall is one of the largest unobstructed indoor spaces in the city; it also boasts an 85-foot-high barrel-vault ceiling. In a city so dense with buildings and population, where artistic spaces are constantly split to allow more simultaneous events, such an open space is a precious luxury that has allowed the Armory to host, since 2007, an astounding array of logistically challenging artistic enterprises, including Christian Boltanski’s No Man’s Land, Ariane Mnouchkine’s Les Éphémères, Declan Donnellan’s Boris Godunov, and the epic opera Die Soldaten.

On the morning of December 1, the Armory’s president and executive producer, Rebecca Robertson, held a press conference to announce the 2011 season and to offer the media a first look at British director Peter Greenaway’s multi-media presentation of Leonardo’s Last Supper (on view December 3, 2010 – January 6, 2011). This is just one piece in a complex ongoing project entitled Ten Classic Paintings Revisited (although there were only nine until recently), in which the artist has set out to create what he calls a “dialogue” between 8,000 years of painting and 115 years of cinema. Greenaway, who was present at the press conference, explained his belief that human civilization began and will end with painting, or – more specifically – that the first mark ever laid down by mankind must have been a painting, and that the last one will be as well. Widely known as a film director, Greenaway actually started out as a painter and can boast deep practical and theoretical knowledge of the subject, including the many legends that surround certain works of art, as expressed in his documentaries Rembrandt’s J’Accuse (2008) and The Marriage (2009), which revolve respectively around Rembrandt’s painting The Nightwatch of 1642 and Veronese’s The Wedding at Cana of 1563. Together with Leonardo's famous work, these three are the first classic paintings to have already been “greenawayed.” For the record, the other seven paintings will be Raphael’s 1504 Wedding of the Virgin, Picasso’s 1936 Guernica, Velazquez’s 1636 Las Meninas, Monet’s 1920 Water Lilies, Seurat’s 1884 La Grande Jatte, Pollock’s 1950 One:Number 31, and, recently added, Michelangelo’s 1541 Last Judgment from the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican in Rome.

Greenaway was born in Wales in 1942, while his parents were there avoiding the London Blitz, and was educated in London. He has been making films since 1966 and is better known for The Draughtsman’s Contract (1982); The Cook, The Thief, His Wife & Her Lover (1989); The Pillow Book (1996) and The Tulse Luper Suitcases (2003). He lives in Amsterdam in a building that directly faces the Rijksmuseum. Being able to visit the museum as much as he wishes, he has developed over the years a very strong relationship with Rembrandt’s Nightwatch, the colossal canvas from 1642, and the most famous painting in the collection. In 2006 he obtained permission to create an “exploration” of the painting, by projecting lights on the actual canvas, thereby defining the method that can be seen today at the Armory. Technically, this practice involves a detailed mapping of the painting - in other words, a digital database that can allow a light to be focused on the tiniest detail while the rest of the painting remains in complete shadow. This technique allows the spectator to see days going by, shadows moving; it accentuates the three-dimensional perception of the perspective and allows Greenaway to convey a story that is accompanied by sounds and other images projected around the room.Although a common technique has been applied to all of them, the three paintings have been approached in very different ways. There are 34 figures in Rembrandt’s masterpiece, which, Greenaway suggests, is an allegory for a conspiracy within the musketeer regiment of Frans Banning Cocq and Willem van Ruytenburch in which each character plays an important role. He expanded on this theory in his feature film Nightwatching as well as in his documentary Rembrandt’s J’Accuse, respectively from 2007 and 2008. His work in Amsterdam, though, was relatively less elaborate. Coinciding with the celebrations for Rembrandt’s 400th birthday (2006), the canvas was placed in a separate room in which the museum’s lights would go down every seven minutes and special lights would be projected to enhance its composition.

It was in 2008 that Greenaway was allowed to stage a one-night-only event before a select audience in front of the original Last Supper in the refectory of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan.This is basically the main course of the three-part meal that was brought to New York, and it features a double-loop presentation revolving especially around the curious sources of light that the Tuscan painter conceived in 1498. According to Milan’s Superintendent for Architectural and Natural Heritage, Alberto Artioli, “Light is the primary instrument for every painter, but Leonardo here presents us with an unbeatable accomplishment by painting two sources of light. In the background, the sunset still sends forth its vivid rays, and the imminent evening is announced with the gradation of celestial blue tones. Light also has a highly symbolic value as it shines directly over Jesus, who sits against the light at the center of the scene. But yet another light source, this time outside the scene, shines upon the characters as though coming from the window on the refectory wall; Judas is the only character being overshadowed, denied by the light, which therefore performs not only as a pictorial element but as a theatrical feature”.

Greenaway perfectly represents these light sources and gives them movement through time, but in this case, unlike the other two paintings, the treat lies not in the illusory spectacle but in being able to see the details of this deteriorated masterpiece as never before. Considering the distance one has to keep from the original Leonardo painting, and the crumbling wall it is painted on, it is actually quite difficult to capture the many pictorial feats accomplished by the painter in this single work. By highlighting certain elements at a time, and by outlining them against their backgrounds, Greenaway takes us to an undiscovered realm and places us in the middle of it, also with the aid of an actual long, narrow table set like the one in the painting.

Fortunately, The Last Supper cannot be moved from Milan, so Greenaway has worked with the Director and Founder of Factum Arte, Adam Lowe, to create an exact, three-dimensional replica of the original masterpiece. In Lowe’s words, “We have developed pioneering technologies that allow us to reproduce absolutely exact two- and three-dimensional copies of any give artwork. […] For The Last Supper, we used high resolution photographic data recorded using a panoramic process by the Italian company Haltadefinizione – through the use of a panoramic procedure with thousands of shots – together with the data of the 3D scan made by the Central Institute for Restoration. The following phase was color matching: we examined hues, tone and character of the color for every single part of the painting. Subsequently, we worked out collectively how to treat this huge amount of data: we wanted to reproduce the complexity of the surface to preserve variations and imperfections. The Last stage consisted in making the surface in the same materials as the original and printing the image using a purpose-built printer that enables us to overprint in perfect registration. The final phase of the work goes back to the hands of expert restorers so that our clone can recreate the emotional impact that is often prevented by the inaccessibility of the original”. The resulting experience is the main, central course of a three-course meal, preceded by a Prologue and followed by an Epilogue.

The Prologue, which takes place in a sort of antechamber to the recreated refectory, is an example of “architectural cinema,” which was first created as an installation in the Italian pavilion at the 2010 World Expo in Shanghai. The audience, standing, is surrounded by many screens that show, one after another, the most famous Italian historic architectural landmarks, such as Pompeii, Florence, Venice, and ancient and post-war Rome, while little excerpts from famous pieces of Italian music (from Vivaldi to Rossini to Verdi to Nino Rota) blast in the background. Cliché.

The spectators are then herded into the “refectory”, where they must wait for the main course to begin. The most exciting part of the whole event was Greenaway himself standing next to the table and telling us, in his beautiful, dramatic British accent, about the objects present at the meal and the theory according to which the table was set as a geocentric view of the Universe (including the planet Pluto, which wasn’t discovered until four centuries later). Then the lights go down and the two loops go by; this allows the spectator to miss nothing that is projected onto the work and to observe the images of the actual tempera on plaster, digitally recreated on a screen on the opposite wall, in place of the crucifixion fresco by Giovanni Donato da Montorfano, which is not recreated in the display.

Finally, the audience is once again herded back into the antechamber, where an excerpt from Greenaway’s work on Veronese’s Wedding at Cana - including some new material narrated by the director himself – is on view. This is much less spectacular, because everything, including the painting, is projected. (Actually, the original show of Veronese’s huge canvas is more interesting, if less enlightening, than The Last Supper. I happened to be in Venice in 2009 at the same time as the opening of Greenaway’s Nozze di Cana; I was lucky enough to see it and was very impressed both by the technical aspect – it included several moments of the day, a city on fire in the background, as well as a thunderstorm – and by the narration. Greenaway found a purpose for each of the 126 characters who were present for one reason or another at the wedding banquet, during which, Christians believe, Jesus performed his first miracle.)As compared with the Wedding show, the Last Supper display seemed lacking in narrative structure, especially since Greenaway’s motive was to find a way to combine painting and cinema. More artistically satisfying attempts at this pairing can be found in Pasolini’s La Ricotta (1963) and Godard’s Passion (1982), in both of which real-life actors are seen trying to recreate paintings. In the former, the actor posing as Christ actually dies of indigestion while on the cross, and the latter is interesting because the actors are recreating Rembrandt’s Nightwatch, as in Greenaway’s Nightwatching.

So in the end what is Leonardo’s Last Supper: A Vision by Peter Greenaway? Is it art or just technique? There is no doubt about how “cool” this project is. Greenaway himself explained that it is aimed especially at the ”laptop generation,” at those who believe that “there was no painting before Pollock and no cinema before Tarantino,” and I strongly recommend it.. But will it last? Will people 50 years from now go to see it as they surely will go to see Greenaway’s movies? Or will future technology dispel what today seems so spectacular? I believe that the second option is more probable, but my admiration for this artist and his legacy leads me to hope that I will be proven wrong.