In 1944, my father, George De Stefano Sr., was a U.S. Army sergeant stationed in southern

Italy. While in

Campania, he and some of his buddies went to Pompeii to see what the locals call “gli scavi,” the excavations of the Roman city destroyed when Vesuvius erupted in August, 79 AD.

They, like many young men before and since, were eager to see one particular aspect of ancient Pompeian life: the dirty pictures. My father remembers visiting one building, which, based on his recollections, must have been the House of the Vetti, an opulent Pompeian home whose walls were decorated with X-rated erotic paintings. But the paintings were concealed behind wooden cabinets with locked doors. For a few lire, a worker would unlock the cabinet doors so my father and his friends could glimpse the shocking images.

When I visited Pompeii more than 50 years later, I could view the same murals without the peepshow obstructions. Moreover, the erotic art objects and artifacts that had been taken from Pompeii and long been kept from public view were on display, in an exhibition at the National Archaeological Museum in Naples called “The Secret Cabinet.”

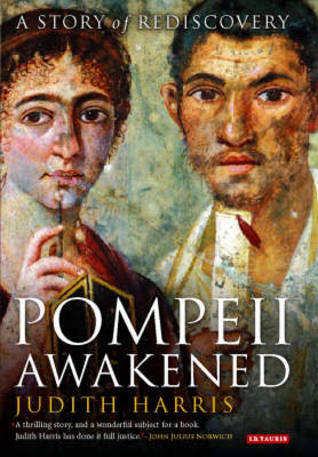

The difference between my father’s and my experience of Pompeii is a modest metaphor for the subject of Judith Harris’ fascinating new book, Pompeii Awakened. Harris, a veteran American journalist who has lived in Italy for four decades, examines how the Western world has viewed Pompeii, the varied and shifting interpretations of the city and its civilization since its rediscovery in the mid-eighteenth century.

Harris observes that in the two and a half centuries since, “the dead city has never lost its uncanny power to fascinate.” More than two million tourists annually flock to Pompeii and nearby Herculaneum (Ercolano). Harris herself got the Pompeii bug when she was a Cleveland schoolgirl. Her interest was piqued by a Victorian novel, “The Last Days of Pompeii,” which was a best-seller for decades and influenced cinematic portrayals of ancient Rome from the silent film era to the present.

Enthralled by the novel, which culminates with the eruption of Vesuvius, she made her first “pilgrimage” to Pompeii as a student. Throughout her career, which has included reporting and commentary for RAI, the Wall Street Journal, Time and the BBC, Harris never lost her fascination with Pompeii, and her cultural history draws upon extensive research. She has interviewed “hundreds of archeologists, classicists, Pompeian scholars and cultural heritage administrators” in addition to visiting

Pompeii “more times than I can remember.” The intrepid Harris even flew over Vesuvius in a hot air balloon.

Pompeii, the birthplace of scientific archeology, has been the testing ground for every discovery and error in the field. New studies of pollen, skeletal DNA, charred plants and even fecal matter left by the Pompeians build upon but also contradict older discoveries. But Pompeii isn’t just about those who once lived there – it is also the story of those who rediscovered the city, the “creative people from all over the world...who devoted their talents, fortunes and their lives…in order to reclaim

Pompeii for the world.”

“Patron and poet, architect and priest, strumpet and queen,” they studied and recreated the site “in their imaginations, for ours, ringing changes in the arts, society, politics, ideas, and the very look of our homes and cities, from wallpaper to the Wedgwood ceramic candy box on the table.”

When Pompeii was rediscovered in the 18th century, “educated

Europe was enthralled.” Until then, “…no one knew, aside from what could be read in books, how the ancient Romans actually lived.”

“To historians, archeologists and scientists,” Harris explains, “Pompeii’s significance lies in its offering a total picture of the ancient world, captured at a single point in time. Other ancient cities, such as

Troy, Angkor Wat, and Native American pueblo habitats were burned or abandoned. The vision they offer is limited and partial.”

Pompeii, though, was “simply blanketed, within the space of a few hours, under a layer seventeen feet thick and more, composed of dust, rocks and, above all lightweight pumice pebbles, resembling gravel.”

From the moment of its rediscovery,

Pompeii evoked vastly different reactions in the minds of Europeans: for some it represented the apex of ancient civilization, an idyllic world; for others “the ultimate in decadence and sin.” (The latter view was confirmed by the erotic frescoes and art objects.) For those shocked by what seemed liked wanton polymorphous sexuality, Pompeii was akin to Sodom and

Gomorrah, and all those who died on that terrifying day in August 79 AD got what they deserved.

Harris evokes the stunning impact of Pompeian erotica on Christian Europe:

Although the 18th-century erudites were familiar with risqué ancient poetry, and possibly had seen vases with obscene motifs and the wall paintings of Etruscan tombs…nothing like this had ever been seen, and surely not in such quantity. From the ruins emerged both mildly erotic and blatantly pornographic scenes, painted on walls and on vases, designed in mosaic tiles on floors, vulgarly scribbled onto street-front walls.

Pompeian erotic art included “gigantic free-standing phalluses,” platters decorated with homosexual group sex scenes, and sculptures of Pan having intercourse with a she-goat. “In discoveries that to this day condition the attitudes toward Pompeii worldwide, objects of an obvious sexual content were found, shocking to many, titillating to others...In

Pompeii, erotic pictures were not a vulgar exception, they were the rule.”

But awakened Pompeii spoke not only of sex and erotica; there were ideological and political lessons to be drawn from Vesuvian antiquity. For Johann Joachim Winckelmann, a politically radical, eighteenth century Prussian art historian, the Greek and Greek-inspired art found at

Herculaneum was great because it had been produced within a democratic state which had a constitution – political heresy in an age of monarchy.

But no one made more ideological hay from Pompeii than the 20th century dictator who fancied himself a Caesar. In perhaps the book’s most compelling chapter, Harris describes how Benito Mussolini used antiquity for political propaganda, to justify militarism, war, and racism.

By the mid-1930s, Fascists “controlled all the tools of culture,” which was central to the regime’s power. “To build a totalitarian state,” Harris notes, “Mussolini had imposed harsh police measures and military controls. But without his cultural politics, this would not have sufficed in such a sophisticated country.” Control over

Italy’s archaeological heritage was a key component of Fascist cultural policy, and Mussolini enjoyed the enthusiastic support of Italy’s antiquarians.

Pompeii was essential to Fascist romanità: the discoveries “showed that majesty of ancient, Imperial Italy with which Mussolini wished to be identified.”

Mussolini’s handpicked administrator Amedeo Maiuri managed the sites at both Pompeii and Herculaneum. Even Maiuri’s opponents, Harris notes, praised his efforts to recover the sites in a systematic, scientific manner.

But, encouraged by Mussolini to “operate on a grand scale,” Maiuri got carried away and unnecessarily cut “great swathes” into the sites; buildings also would be stripped and allowed to decay while the best findings went to the Naples archaeological museum. The remainder were sold legally to foreign museums or illegally ended up in private collections.

“Mussolini’s overly aggressive excavation of Pompeii…in order to exploit archaeology as a propaganda tool…wreaked more destruction than all the Austrian captains of fortune, the arrogant Spanish, the drunken custodians of the early Risorgimento and the thieving bandits of Vesuvius.”

After World War II, Maiuri, the ultimate bureaucratic survivor, resumed his explorations. He triumphed with the excavation of a Greek library in the Villa of the Papyri at Herculaneum. The library, the only extant one from the ancient world, contained caches of papyrus scrolls. Harris provides an absorbing account of the contents of the fragile scrolls, philosophic works of prominent Stoics and Epicureans, as well as scientific texts and scripts of plays.

Vesuvian territory continues to be excavated. The latest and most important recovery is of a complex of buildings buried near the town of

Somma Vesuviana. But Somma Vesuviana lies directly beneath Vesuvius, “and therein lies the next threat” to the site – an overdue eruption of the volcano. In 1999, a committee of scientists warned that Vesuvius, “which harbors a destructive force greater than that of a nuclear bomb, is among the world’s fifteen volcanoes most likely to erupt.”

If that were to occur, the results, Harris says, will be dire indeed: “As has happened for at least four millennia, all in its path will be entombed – people, first of all.” But despite government offers of compensation, inhabitants of towns and villages on the slopes of the volcano refuse to leave their homes. Harris finds one bright spot in this dark scenario: “advances in vulcanology should allow advance warning…Despite chaos, many will escape, as they have in the past. Even at

Pompeii, home to something between 15,000 and 20,000 people in August AD 79, only 2,000 skeletons have been found.”

Buried and rediscovered many times, Pompeii and the other “lost cities of Vesuvius,” Harris concludes, continue to “haunt the imagination.” For anyone who has walked the stones of those ancient cities, and anyone who intends to someday, Pompeii Awakened is essential reading.

Source URL: http://iitaly.org/magazine/focus/art-culture/article/pompeii-awakened-dead-city-still-speaks

Links

[1] http://iitaly.org/files/1006pompeii97818451124171199118885jpg