ROME – Assailed by a hailstorm of legal troubles, one-time Premier and Senator Silvio Berlusconi, 79, was kicked out of the front door of the Senate thirteen months ago. This week Berlusconi returned, albeit through the back door, thanks to his year-old political agreement – some are now calling it an embrace – with Premier Matteo Renzi known as the Nazareno Pact.

A vote in the Senate Jan. 21 was called to eliminate 35,800 amendments to the ambitious reform bill known as the “Italicum,” whose aim is to make Italy’s election system more efficient. That sounds good, but, because the bill hands considerable power over the choice of candidates to the party bosses, leaving rank-and-file party members little choice, a hefty faction within Renzi’s own PD has fought against the Italicum as it is currently written. The tsunami of hostile amendments was, in fact, theirs. However, the importance of the actual passage of a reformed election law, in the works now for eight years, cannot be understated. Among the other conditions in the Renzi bill:

-- To have parliamentary representation a party must obtain 3% of the vote.

-- In order to avoid small parties from blocking votes, the party winning more than 40% will obtain automatically obtain 340 seats in the 630-seat Parliament

-- The powers of the Senate will be severely reduced so that the decisions in the Chamber of Deputies will not be rejected, creating an endless back-and-forth stalemate

Leading the PD opposition to Renzi on this is Professor Miguel Gotor, an historian and neophyte politician who is the de facto stand-in for Renzi’s real adversary within the party, hardliner Pier Luigi Bersani, PD secretary from 2009 until Renzi succeeded him in 2013. When the vote on dropping the amendments was called, the Gotor-Bersani group of 27 senators voted against their own party, complaining that Renzi would not even negotiate with them – “He only talks with Berlusconi.” The result: despite their defections, Renzi won – but only thanks to 46 votes from Berlusconi’s Forza Italia.

Renzi defends the Nazareno Pact as an informal coalition limited solely to specific reforms in the larger interest of the nation. Berlusconi views the Renzi version of the Italicum as a way to encourage the center-right parties (which include Alfano’s Alleanza Nazionale) to merge. Needless to say, complaints poured in from all sides. “The Nazareno pact is now transformed into the Nazareno party,” in the words of one discomfited PD senator.

Nor was everyone in the Berlusconi camp pleased, and at least ten Forza Italia defectors refused to follow Berlusconi’s orders to vote with Renzi. They had a point: in theory Berlusconi is a leader of the opposition to Renzi’s coalition government, whose partner is a Berlusconi breakaway, Angelino Alfano. Said Raffaele Fitto, leader of the Forza Italia dissidents fighting the Berlusconi line, “It was an incredible error on Berlusconi’s part. He is killing Forza Italia.|

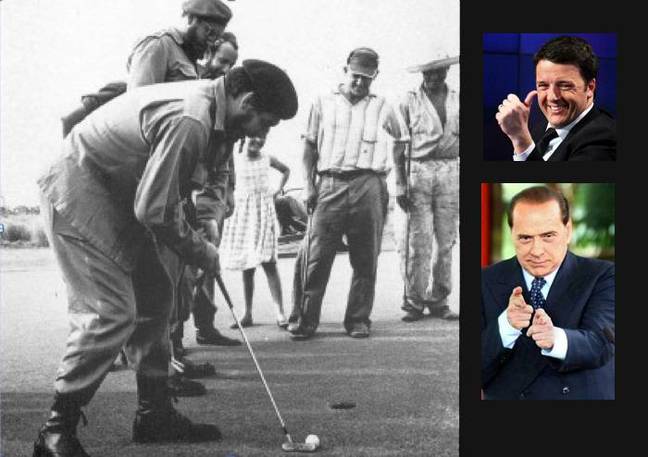

Just a year ago Berlusconi and Renzi held a long private meeting at Largo del Nazareno, near the church of Sant’Andrea delle Fratte in Rome, in a building that now houses the national offices of Renzi’s Partito Democratico (PD). Overlooking the two during the meeting were photos dating from the pre-PD political past of the Italian Communist party, including a shot of Fidel Castro playing golf with Che Guevara.

At the time of that meeting Italian politics were at a standstill, thanks to a seemingly unbreakable three-way political split pitting Berlusconi, whose party is again called Forza Italia, on the right, against the center-leftish PD under Renzi and Beppe Grillo’s wild card Movimento Cinque Stelle (M5S). The aim of the accord hammered at that time between Renzi and Berlusconi was to work together basically against Grillo.

The final vote on the Italicum takes place next week, and Gotor promises that the PD dissidents will continue their opposition despite appeals for them to support Renzi’s version of the Italicum. Renzi himself supposedly said in private that, “They [the defectors] are making Berlusconi a central figure again.” Many others here are critical of the minority faction’s obstinacy, on grounds that the dissidents should either leave and create their own party, or back Renzi so that he has no need to negotiate with Berlusconi, in whatever political swap may lie in the background.

The same Berlusconi-Renzi informal coalition is expected to play a key role in Italy’s next urgent vote, which begins in just one week: election of a president to replace Giorgio Napolitano.