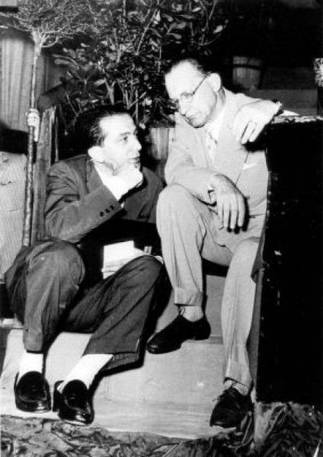

ROME - The death of Giulio Andreotti marks the end of an era. He was the last important figure of the first Italian republic, and as such his death on May 6 was a top news story in Italy and worldwide. For many at home it was also an occasion for soul searching. Countless Italians of every walk of life remarked that, whatever his sins might have been, Andreotti loomed larger than those trying to fill the political shoes today. He was born way back in 1919, and, when I first met him in the early 1960s, he was an already seasoned politician who did not miss a beat. He slept little, read omnivorously, was ever cordial and somehow managed to attend every appropriate event, and not only those organized by his Christian Democratic party, the DC.

In later years he was accused of going too far in allegedly having secret meetings with Mafia bosses. By one account these began with an attempt to stop the Mafia from hounding Piersanti Mattarella, an unusually decent Sicilian Catholic politician who became President of the Region in 1978 and fought the Mafia. For his pains Mattarella was murdered in 1980. Later a Mafia turncoat told investigators that he had seen Andreotti give a polite kiss on each cheek to a notorious boss. Andreotti's biographer, Massimo Franco, denies that there is no evidence for either incident and retorts, "Andreotti does not kiss even his wife." Twice Andreotti was tried on alleged Mafia association but never convicted. In one case he was cleared, in another, the statute of limitations ran out so there was no pronouncement.

What is true is that Andreotti's link to the Mafia was a link to Sicily itself, and in the early postwar years, like it or not, the Mafia was very much part of the Sicilian establishment. The majority Christian Democratic party (DC) was ever forced to fight for its life (albeit with U.S. financial backing and Roman Catholic Church moral backing) against the Communist party (the PCI, with a quarter of Italian votes and Soviet financial backing). For the DC, Sicily provided 20% of its party members, meaning that the island represented, within the party, a particularly strong power base.

The Sicilian DC, moreover, was not the sole party in Sicily which had factions with links to local Mafia organizations that turned out and guaranteed the vote. Prior to Sicily's becoming in the 1980s the world capital of heroin manufacture, after seizing the title from the French - that is, in its pre-drug era - the Sicilian Mafia was, in its way, an accepted part of the entire Sicilian society. A Sicilian journalist told me of attending an important event in Palermo in the Seventies. On the platform were the authorities including the local politicians and a priest. Just before the event began the local Mafia boss walked in, to applause, and sat down in the empty seat left for him in the front row. He was not on the platform, but it was as if he were. This was Sicily at that time - the real Sicily.

Andreotti in the meantime had been the DC's go-between with the Vatican, in a period when the Church was selling vast swaths of land for construction projects, especially housing developments. He had personal relations with at least six pontiffs. It is a safe guess that the DC as a party (but not, as today, individuals filling their personal pockets) took some benefit through the negotiations between Vatican and the contractors building the new Rome. In short, if Andreotti were the negotiator between Pontiff and state - and the DC was the state - he had limited interest in Sicily.

At that time the Sicilian organization was headed by Vito Ciancimino of Corleone, DC mayor of Palermo who was expelled from the party in 1984 after his arrest for Mafia association. Ciancimino was responsible, according to magistrates, for the "most explicit infiltration of the Mafia in the public administration" and as such was convicted by the Italian supreme court to a total of thirteen years in prison. When Amintore Fanfani left as the coordinator between the Sicilian and the national DC, Andreotti inherited the running of that tainted Sicilian organization, whose importance, as he once admitted, "I underestimated." Fighting the Sicilian Mafia, however worthy a cause, was not his priority. Doubtless it should have been, but one should also bear in mind that, over the decades, Andreotti was serving seven times as premier and in twenty-two other governments, as a cabinet minister.

Unlike that of Margaret Thatcher, Andeotti was not given a state funeral nor was the body of this life-time senator laid in state inside the Senate. Instead his funeral three days ago took place in private. In death others came to him, both while he was lying at home in Rome and in the private funeral in the nearby basilica of San Giovanni dei Fiorentini, his parish church. Among those who called at Andreotti's house before the funeral were President Giorgio Napolitano and former Premier Mario Monti. Most significantly, the Senate President Pietro Grasso, whose long experience as an anti-Mafia prosecutor, also attended.

What most here were saying is that his secrets, whatever they were, died with Andreotti. He has however left massive archives which are expected to shed light, not on the mysteries of Italy (if those papers ever existed, they have surely been destroyed), but on the entire postwar governance of Italy.

Source URL: http://iitaly.org/magazine/focus/op-eds/article/giulio-andreotti-larger-life-even-in-death

Links

[1] http://iitaly.org/files/giulio-andreotti-e-alcide-de-gasperi-21368403489jpg